Many years later, facing his younger brother, the sexagenarian Augusto Miranda Brasão was to remember that since the age of 12 he worked with his father cutting piassava to pay off debts to his bosses. This palm tree, whose coarse fiber is used to make brooms, has marked the life of Augusto, his brother, father and grandfather. For a hundred years, the different generations of the Brasão family have lived under a criminal enterprise that bind thousands of indigenous extractivists on the upper and middle Negro River, in the state of Amazonas. The brothers live in the community of Malalahá. Just like in the novel “One Hundred Years of Solitude” by the Colombian writer Gabriel García Márquez, the life of piassava workers is repeated in cycles and has a dose of magical realism. They are trapped in a world of exploitation in which work is confused with debt payment, a situation that recalls times gone by.

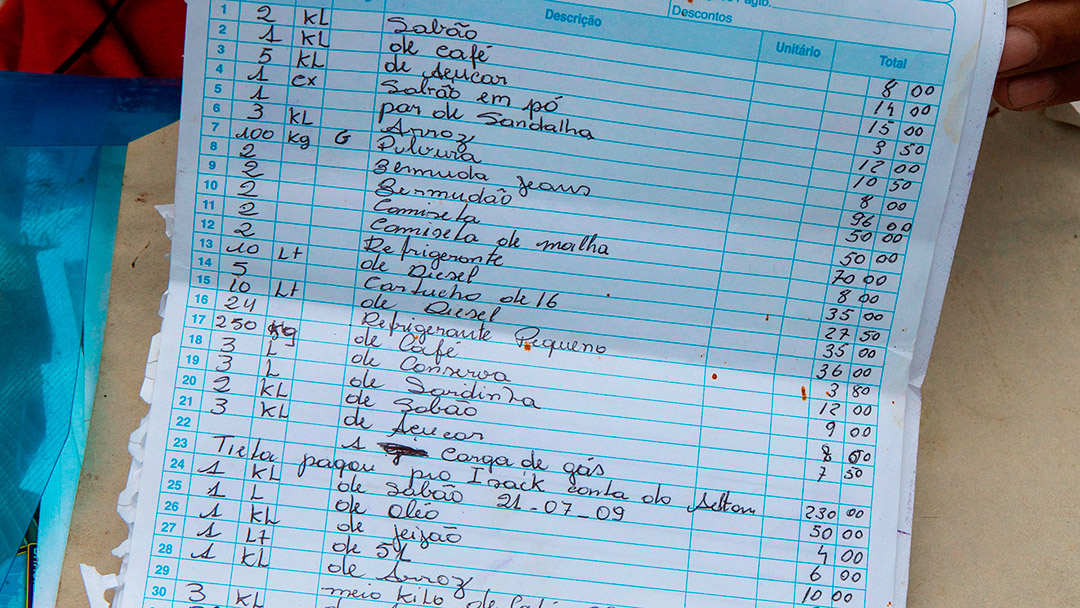

The working relationship is based on a system of loans provided by the bosses who control piassava production. For enough food to last a month, the bosses charge nearly R$1,500 – some items cost 300% more than similar products sold in the town. A kilo of piassava, meanwhile, is worth around R$2. The workers receive what is left (when there is something left) after deducting the loans for the rancho – the name given by the local population for food, transport and basic working equipment. From the amount paid at the end of the month, the employer also withholds 20% for potential impurities. And in some cases another 10% is deducted for the “rent” of their place of work by those who claim to be the owners of the area.

Working conditions. A piece of canvas tied to wooden posts makes their accommodation. There is no bathroom, sink, place to store food or safety equipment. The workers eat what they hunt. Photo by Fernando Martinho

“The goal is to keep the piassava worker indebted and subordinate their whole life,” explained the researcher Márcio Meira, former president of the National Indian Foundation (Funai), who has studied the cycle of bondage in the Amazon. The inhabitants of the Negro River call this system aviamento. But the official name for this form of contemporary slavery, according to the Brazilian Criminal Code, is debt bondage.

However, a decree that would not consider this type of exploitation as slave labor was published on October 13 by Labor Minister Ronaldo Nogueira, who wants to change the current definition. “The decree does away with the concept of contemporary slavery,” said Antônio Carlos de Mello, coordinator of the Programme to Combat Forced Labor of the International Labour Organization in Brazil. According to Rafael Garcia Rodrigues, a labor prosecutor and former national coordinator of Slave Labor Eradication at the Office of the Public Prosecutor for Labor Issues, the decree could “abolish” the concept of debt bondage. “It’s an unbelievable setback.” The decision of the government, without any prior discussion, comes ahead of a new impeachment vote in the Lower House of Congress and a week after the dismissal of the national coordinator for policing slave labor, André Roston.

Many piassava workers are the first to deny that their working conditions constitute slave labor. “What would happen if they reported it? How would they get back home with nothing? It’s a trap,” said Alexandre Arbex Valadares, a researcher at the Applied Economic Research Institute (Ipea). He explained that once they start, the worker has no other alternative than to survive and pay their debts.

These conditions, however, are viewed as normal by the piassava workers themselves. Augusto, trapped in the system for 48 years, says he is free and that he only works when he wants. “Nobody here forces me to do anything.” He and his brother spent that day, May 28, 2017, working to pay off a “little debt” of R$800 with nearly a ton of piassava. Cutting palm leaves in temperatures that can exceed 30º C in the fall and carrying 60 kilos at a time on their backs is only half the day’s work. While they wait for a tapir that they hunted to cook, Augusto explains that the boss requires them to cut, comb, trim and tie the fibers up into bales. “But we’re not slaves, like people say we are.”

In Brazil, according to the IBGE (Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics), 1.5 million people are unable to leave their employment due to some kind of debt.

In the community of Malalahá where they live, the person giving the orders is the boss Edson Mara Mendonça, say the piassava workers in the region of the upper Negro River. But he is not the only one. Debt is encouraged by other bosses who travel to the communities in search of piassava workers. Jucileno Neves Pacheco, a 59-year-old from the state of Bahia, owes R$400 to another boss, but out of fear of reprisals he preferred not the reveal his name. “I’ve got product to pay for, but first I have to buy some oil and gasoline from him to collect the fibers”. In other words, in order to pay the debt, the worker must first take on a new loan. And then there’s the tape, remembers Pacheco. A 300 meter roll of tape used to tie up the leaves costs, on average, R$400. Tying the fiber into bales makes it easier for the boss to transport. “To begin with, we thought the tape was a good idea, because we thought it would be provided [by the boss]. But no. When they saw that they could make money, it started costing us more. And it doesn’t serve any purpose at all for us,” said Pacheco.

For one piassava worker with sad eyes, 41-year-old Alberto Neres da Silva, bondage appears to have robbed him of his capacity for emotion. “One by one, I lost my children,” he said calmly, about a story that should have been told like it is: a tragedy. In distant times in his life, and each time working in piassava extraction, he lost three children. They all died before they were one year old due to the precarious living conditions on the piassava plantations. Many, like Neres da Silva, take their whole family upstream with them. This allows them to reduce food costs and avoid living apart for three weeks each month.

Two of his children got sick inside the plantations and were buried there. The first time, the boss did nothing to help, said Neres, without expressing any indignation. The second, a manager refused to offer any assistance because “the boss had not given the order”. The third time, Neres made it to the local community in time. When his son started to show signs of recovering, the boss found him to tell him that the infant would be fine. “I owed money and I took it as a warning. I went back upstream and after two weeks, my son’s condition deteriorated. The boss only arranged for a speedboat after the boy was more dead than alive.” He got the tattoo on his arm after the third death: “God is powerful, I have faith”.

The debt economy was introduced to the Negro River during the rubber boom. One of the accounts of the Italian Ermanno Stradelli, who traveled up the dark waters of the river in 1881, states that debt gave the indigenous peoples – to this day the majority of the population in the state of Amazonas – the status of being “civilized”. In the words of the Italian, “the man who does not owe money is a man without value.” The statement appears in the book Baré, Povo do Rio, published by Edições Sesc. To avoid conflict with the boss, according to the researcher Elieyd Sousa de Menezes in her master’s thesis, foreigners encouraged interracial marriages.

In Malalahá, bondage has created a situation that is unusual to say the least. The piassava worker Olânio dos Santos Bento, aged 28, explained that his father, Olavo, aged 88, is his boss. “But he’s not like the other bosses,” he said. Olânio’s debt was R$800. He caught “leishi”, or Leishmaniasis, a disease caused by parasites. Prevented from working due to pain, his debt accumulated. “My father was a great boss. He had 60 men working for him,” he said with pride. Olânio’s brother is a “little boss”, a small tradesman, who on one of his trips upriver played soccer with the indigenous locals. Social mobility in the debt bondage chain is possible when a worker has the means of production, which is rare.

Olavo, the father, has lived on a boat for 50 years. On the floor of the vessel is all kinds of food and accessories. Like his son, the grandson of his Portuguese father and Baré indigenous mother, Olavo was a piassava worker. Like his son, he doesn’t hesitate in saying “there’s not a single indian here” about the residents of Campinas and other communities. “Indians live in isolation,” he said. “The rest are caboclos.” And he doesn’t have a good word to say about them either. “A good piassava worker doesn’t have big eyes [greed],” he said, before citing an example of a good worker, in his opinion. “There was a guy who waited for everyone before getting his food. And he didn’t eat wheat products, biscuits. It was water, salt and whatever he could hunt.” Then, surprisingly, he said that “running up a tab makes life difficult” – precisely the system that he still uses with his workers. Asked about this, he was speechless for the first time.

“A good piassava worker doesn’t have big eyes [greed],” he said, before citing an example of a good worker, in his opinion. “There was a guy who waited for everyone before getting his food. And he didn’t eat wheat products, biscuits. It was water, salt and whatever he could hunt.”

All across Amazonas, the pejorative expression “those who aren’t indians” used by Olânio and Olavo is a common way to refer to the Baré indigenous people. Like so many other indigenous groups, the Baré were persecuted in the early decades of the 20th century. In Baré, Povo do Rio, indigenous people and researchers mention illegal occupations, massacres both physical and cultural – such as the forced introduction of Catholicism – and imprisonment and slavery. To survive, they concealed their own identity. They lost their rituals and native tongue. The strategy to disappear worked so well that Funai declared the group extinct. In 1990, the recovery of their identity began.

“The alliance of so many peoples around an indigenous issue is, above all, an alliance for survival. They undertook this process so they wouldn’t be decimated,” explained the anthropologist Camila Sobral Barra, who studies the peoples of the Negro River for Instituto Socioambiental (ISA).

The search for identity is associated with the search for land. “With demarcation, the land returns to the indigenous peoples and stops generating profit for the piassava bosses, businesspeople [from the agribusiness and mining sectors] and for politicians,” said Barra.

An appropriate response

In 2013, the Cooperative of Piassava Workers from the Upper and Middle Negro River (COOPIAÇAMARIN), known locally as the association of bosses, organized an anti-demarcation march in Barcelos. They used the report by the anthropologist Edward Luz, which was commissioned and rejected by Funai because it was drafted without hearing the indigenous people. Luz is an evangelist from the New Tribes Mission Brazil, an organization that was banned from indigenous communities in 1991, accused of trafficking children, slavery and sexual exploitation. In 2013, Luz left the Brazilian Association of Anthropology.

Four piassava workers told Repórter Brasil that COOPIAÇAMARIN had paid the fuel costs for them to travel downstream and join the anti-demarcation march. The effort brought together nearly a thousand people with signs and cars with loudspeakers – the banner “I am a piassava worker, I exist” is still there – and brought the town of 25,000 inhabitants to a standstill. The intention was to defend the interests of the bosses, but it had the opposite effect. The march drew the attention of the Office of the Public Prosecutor for Labor Issues (MPT). “We thought there were only a few extractivists and all of a sudden a thousand were there in front of us,” said the MPT prosecutor Renan Bernardi Kalil. Contacted several times, COOPIAÇAMARIN could not be located.

A year later, prompted by the stories they heard at the demonstration, the MPT, the Ministry of Labor, the Federal Prosecutor’s Office, the Federal Highway Police and the Army conducted a field raid.

Carried out in April and May 2014, the action rescued 13 piassava workers. They worked for a boss known as Carioca, the nickname of Luiz Claudio Morais Rocha, the owner of the company Irajá Fibras Naturais da Amazônia, whose legal name is L. C. Morais Rocha Comercial. One of the workers owed nearly R$20,000, a debt that had accumulated over thirteen years of bondage.

The final report concluded that the group was living in conditions akin to slave labor, and identified a total of twenty-six labor irregularities. The conditions were classified as debt bondage on account of illegal indebtedness and remuneration below the minimum wage – the same situation faced today by the piassava workers interviewed by our reporters.

“An example of how the repression of slave labor is ineffective when it is also the only strategy to combat the crime,” said the federal prosecutor Julio José Araújo Júnior, who participated in the rescue action in 2014. The Regional Federal Court of the 1st Region, in Brasília, accepted the civil lawsuit against the boss Carioca. The sentence of Federal Judge Jaíza Maria Pinto Fraxe on the labor violations suffered by the piassava workers was the subject of an award this year from the National Justice Council, a body that oversees the Brazilian judicial system.

The criminal proceeding had a different outcome. A new prosecutor took over the case and argued for the acquittal of Carioca. In August this year, Federal Judge Ana Paula Serizawa Silva Podedworny acquitted the boss due to lack of evidence. The press office of the Federal Prosecutor’s Office informed that the original prosecutor of the criminal case has appealed the judge’s ruling.

When contacted, Carioca denied the charges. By telephone, he said that the rescued piassava workers did not work for him and that he does not have shacks in that location. “They brought it from there and sold it to me. Sometimes, I traded gasoline. But they (the inspectors) said I can’t do that anymore.” About trading on the river today, he said: “After everything that’s happened, whatever I buy I’ll pay for up front.”

According to local residents, now that Carioca is out of the picture, the tradesman Antonio Lacerda has emerged as the new boss in the region. The Repórter Brasil team visited the community of Tapera, where the business is based. Tons of piassava bales were piled up on the banks of the river, on the river itself and even underneath the houses. All the residents would say, out of fear, was that Lacerda wasn’t there. The team of reporters tried to locate Lacerda up until the time of publication, but was not successful.

Fear of leaving bondage

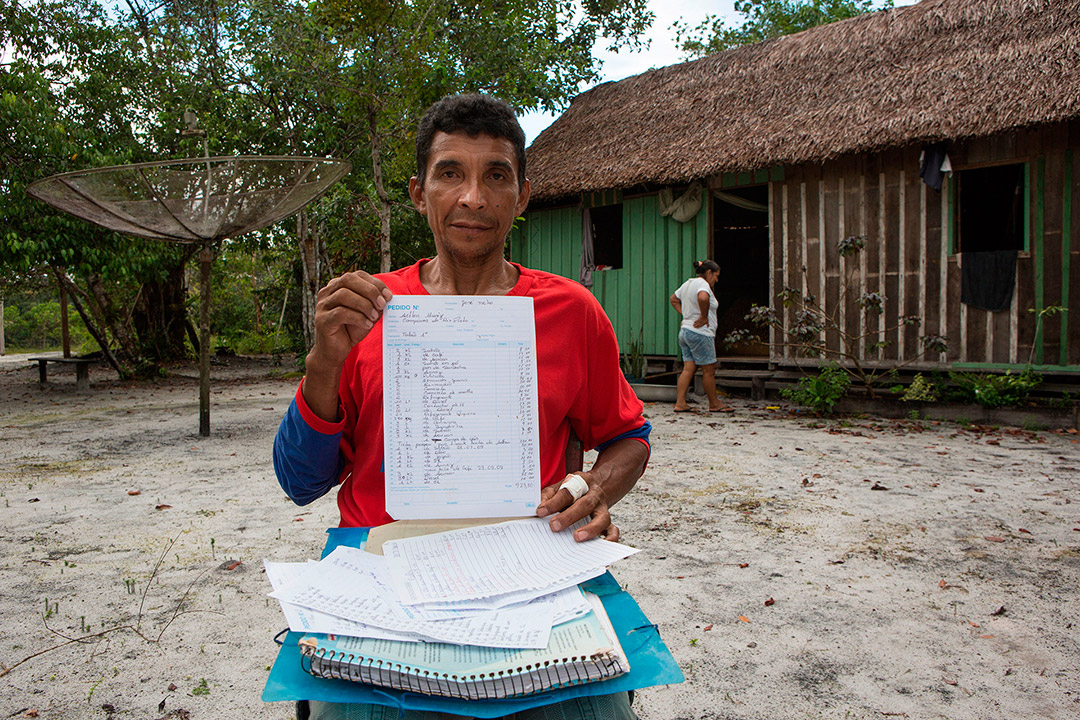

The piassava worker Ailton Pereira, aged 46, lost an uncle and a father-in-law after they were bitten by snakes in the plantations. Since the trunks are covered in fibers – in the Tupi language “hairs that grow from inside the heart of the tree” – the piassava is used as a nest by poisonous animals. “I’ve come close to being bitten several times myself, not including the mosquitoes,” he said. In piassava plantations, it is common to see barber bugs, which transmit Chagas disease, as well as transmitters of malaria. Umbilical hernias, low back pain and early rheumatism are also common occupational diseases.

The father of six living children, aged from 2 to 22, Ailton said he needed courage to leave the piassava plantations. Instead of making bails, today he makes handicrafts with the fibers and sells them in commercial centers. For a broom, he earns R$7. In the community where he lives, he is known as the author of a song about the life of piassava workers. “I got tired of cutting and carrying tons of piassava and always being hungry, for weeks at a time, in the middle of the forest.”

Fear is the greatest tormentor of those who stay. At least according to José Melgueiro de Jesus, aka Zezão, president of the Association of Communities of Rio Preto. “When I was a piassava worker, life was bad but I didn’t leave because I didn’t think I could survive any other way.” He glances at the river, where he left his past behind. “To tell you the truth, I wouldn’t have been able to do it without my wife.” Laudiceia Carvalho Balbino, aged 46, had been insisting for years that they make a change to their life.

The same water that trapped them set them free. Laudiceia recalls the day when Zezão was trying to control the canoe during a storm. Their two small children were hanging on by themselves because Laudiceia was holding their newborn.

The wind blew a branch that hit her on the head. The shock and the pain gave way to anger and she gave her husband an ultimatum. “I was crying and I swore that we’d be able to live differently,” said Laudiceia, while cooking cassava flour in a clay oven.

“After I stopped working with piassava, I could get to know my wife and children again,” said Zezão, talking about one invisible impact of bondage, in which men, through no choice of their own, become mere spectators of their own future. They moved to Campinas do Rio Preto. They took a course in family farming and planted cassava on a piece of land 20 minutes by boat from the community. The workday starts at dawn and ends in the late afternoon. Zezão and Laudiceia cannot count how many times they have had “tremors”, a classic symptom of sunstroke. “Physical work is a sacrifice, but it is blessed. People who plant land don’t go hungry”. Today, they help their neighbors who are trying to get out of bondage by telling them about their own journey and giving them food.

Demarcations on the Negro River

The cost of beating the system of debt bondage has been high for Zezão, who is now a community leader in Campinas where he lives. In May, the Federation of Indigenous Organizations of the Negro River (Foirn), an umbrella organization of 89 associations and more than 35,000 indigenous peoples, held a meeting in the town with local leaders to talk about the demarcations. At the meeting, the Yanomami indigenous group accused Foirn and all of Campinas of being enemies. According to Zezão, the Yanomami think that demarcation will close off the rivers and prevent them from working. “But they didn’t dream that up. There are people behind all this. What they want is indians fighting indians,” said Marivelton Barroso, president of the federation.

Even Mayor Araildo Mendes do Nascimento, say the residents, has given conflicting versions about the demarcations. In the community of Campinas, Careca – the nickname of the mayor – has promised to check on the progress of the demarcation processes. In the community of Malalahá, a different promise was made. “[The mayor] told the minister not to sign,” said Olânio, of Malalahá, referring to a private conversation he said he had with the mayor. Careca is from the center-right Brazilian Democratic Movement Party (PMDB), the same party as the former Justice Minister Osmar Serraglio and President Michel Temer. Serraglio, who has connections with agribusiness, has made countless statements critical of the demarcations. When contacted, Careca did not answer the telephone calls made by our reporters.

Barroso, aged 26, has been an activist for the indigenous cause since he was a teenager. Without hesitation, he calls the environmental agenda of President Michel Temer a “setback” and accuses the government of negligence. He has the determined voice of someone who has already denounced the government in the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights and this, he said, has assured him a long list of anti-demarcation enemies – from bosses to politicians. According to Barroso, demarcation will guarantee the autonomy of indigenous peoples in the production and sale of piassava.

On the upper and middle Negro River, it has not been a matter of hours, days or months. For years whole families have been subjected to exploitation through debt bondage in the extraction of piassava. Although many still cannot understand – or admit – the violations they suffer, there is a growing movement that is eager to create, for the first time, a new beginning in the dark waters of the river.

Taste of Amazonas. In the communities along the river, açaí berries are picked for home consumption and for sale. Photo by Fernando Martinho

Translated by Barnaby Whiteoak