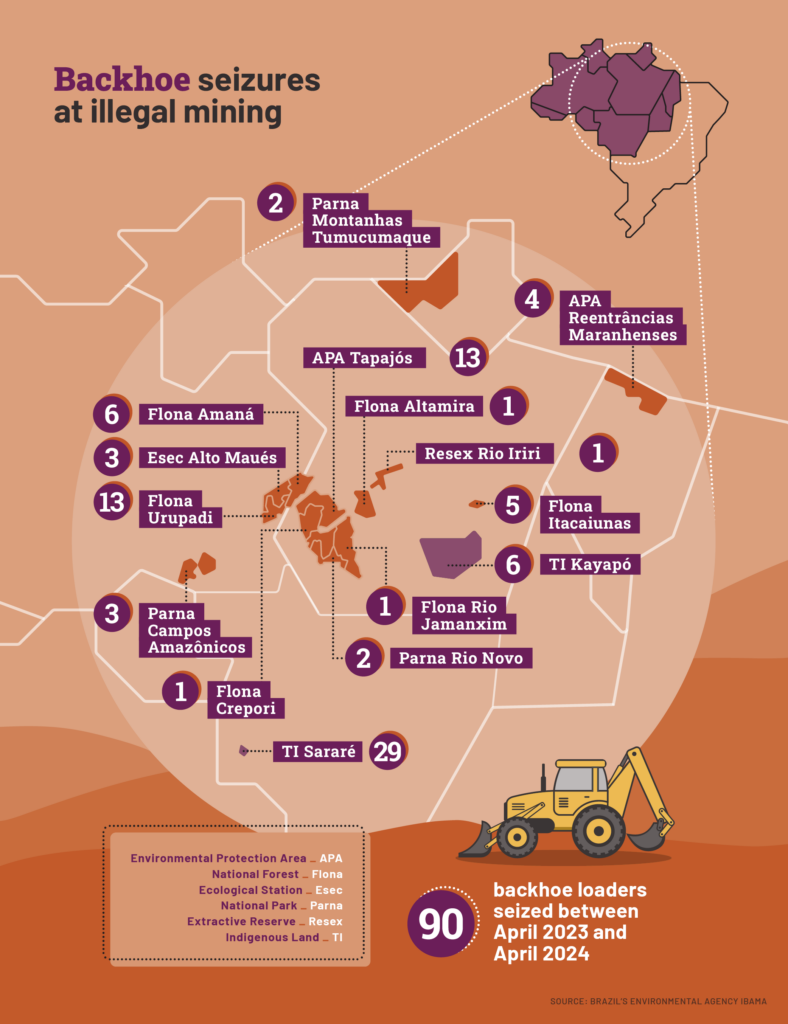

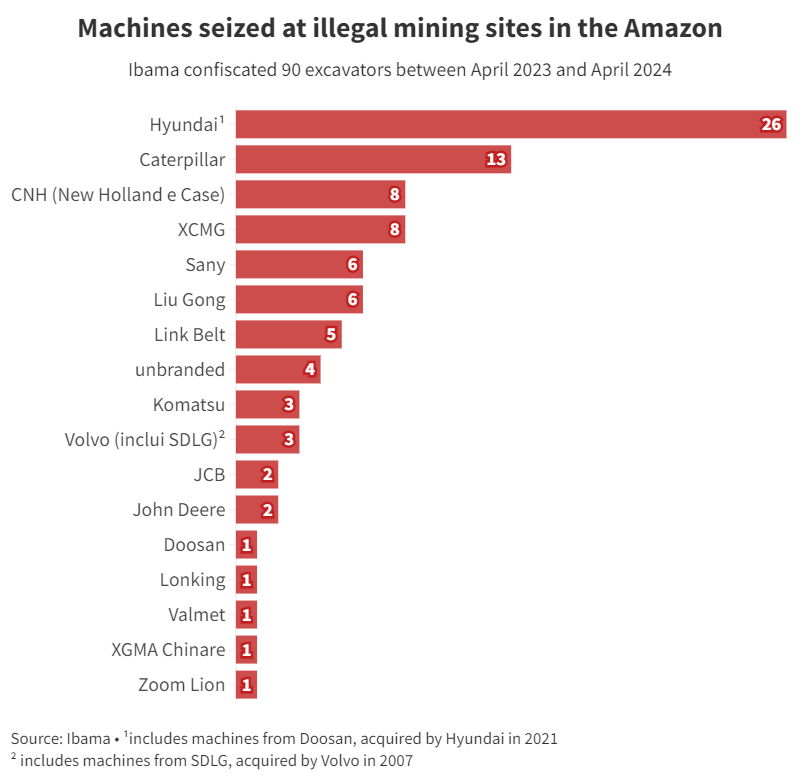

IN A YEAR, 90 backhoes were seized on indigenous lands and conservation units in the Amazon. The construction machinery found in mining areas is estimated at €7.6 million. The South Korean company Hyundai Construction Equipment topped the ranking, with at least 26 backhoes detained between April 2023 and 2024 in Brazil. The American company Caterpillar ranked second, with 13 machines seized during the period.

The use of heavy machinery in mining has scaled up illegal activities in the Amazon, contributing to the advancement of destruction. An excavator can do it in 24 hours which would take about 40 days for three men to accomplish.

The survey was conducted by Repórter Brasil with data from seizures by Ibama (Brazilian Institute of the Environment and Renewable Natural Resources), the Brazil’s environmental agency. The brand of the equipment is not always recorded in the seizure terms. For example, two of the six machines confiscated on the Kayapó indigenous land in June have no identification.

In 2022 alone, about 35,000 hectares of mining areas were detected, an area three and a half times the size of Paris, according to the most recent survey from MapBiomas. The mined area grew by 190% in conservation units and indigenous lands, compared to the 2018 scenario in Brazil.

“The Hyundai machines are not only for farmers and construction, but they are also for destroying the forest”, says Doto Takak Ire, president of the Kabu Institute and member of the Alliance of Peoples Against Mining – a coalition of the Kayapó, Munduruku, and Yanomami indigenous peoples to combat illegal activity.

Last April, Takak Ire went to South Korea to demand accountability from Hyundai after a Greenpeace report uncovered 75 multinational machines on Kayapó, Munduruku, and Yanomami indigenous lands. “Everything changed with the arrival of the machines”, explains the indigenous leader. “The loader digs deep into the ground, eats away at the banks of the streams, and widens the river. It’s a huge destruction”.

A year after Greenpeace’s report, however, Hyundai machines continue to contribute to the destruction of the forest.

In addition to Hyundai and Caterpillar, other multinational companies were caught supplying illegal mining with heavy machinery. CNH, the owner of New Holland and Case, ranked third with eight seizures, as did XCMG (China). The Chinese companies Sany and LiuGong tied for fifth place with six machines each.

“The trade of these machines is free, there is no type of restriction. There is no control whatsoever, and this is incompatible with the importance they play in illegal activities in the Amazon”, warns Felipe Finger, coordinator of Ibama’s Special Inspection Group.

When contacted by Repórter Brasil, Hyundai stated that it has been collaborating with the competent public authorities and providing information and documents requested to assist investigations and identify alleged illegal miners using their machines and equipment in the Amazon region. It also said that currently there is a “rigorous assessment process of the integrity of customers and immediate blocking of customers and consumers suspected of involvement in illegal mining activities”. According to the company, sales control “includes requirements for all customers and consumers to declare that the machines and equipment will not be used for illegal mining purposes”.

Fourteen other manufacturers were identified in the survey. Repórter Brasil contacted all companies, but only Volvo, Link Belt Excavators, John Deere, and JBC responded until the publication of this report. The companies stated that the responsibility for activities performed with the machines lies with the customer after acquiring the equipment.

Those with location control technologies, such as Volvo, Link Belt, and John Deere, also said they could only access the information with prior authorization from the owner of the excavator, in compliance with Brazil’s General Data Protection Law. Komatsu said it has systems that detect when machinery enters protected areas, but that this monitoring “becomes more complex” when operators “intentionally remove various trackers and electronic solutions from them”.

The full responses from the manufacturers are available at this link. The space remains open for comments from other companies.

Inspection by Ibama

Ibama’s operations even destroyed brand-new excavators in the Sararé Indigenous land – one with only 44 hours of use and valued at 645,000 USD from the Link-Belt brand. “This reveals an impressive investment,” says Finger.

The inspectors also found a new Hyundai machine in an unusual situation: buried in a hole and covered with palm leaves. Painting the excavators in neutral colors to hide the typical color of this machinery or changing the work shift from day to night are other strategies used to evade inspection.

Indigenous Nambikwara under pressure

The indigenous land with the most seized machines was Sararé, occupied by the Nambikwara people, located on the border between the state of Mato Grosso and the state of Rondônia. In the past year, 29 excavators were seized – 11 of which are from Hyundai.

Mining, which was already observed in the southern part of the state of Pará, is migrating to the Nambikwara’s territory. Increased enforcement actions in Pará and the “gold rush” in the indigenous land in Mato Grosso caused a “mass exodus of miners and machinery to Sararé area”, explains Finger from Ibama.

Furthermore, the ease of access by land in the Sararé indigenous land may explain the explosion of mining in the region. Taking excavators into Munduruku and Yanomami indigenous lands, for example, requires complex logistics of transport by river and air. “Criminals have a great facility to organize and provide logistics for illegal activities in Sararé [by land]”, the inspector says.

ASSINE NOSSA NEWSLETTER

Uncontrolled Sales

A new excavator can cost up to between 147,500 and 276,500 USD, according to inspectors, and a used one doesn’t go for less than 36,000 USD. “It’s not like bread that you buy every day, who has the capital to buy that? Most of those working in mining in the Amazon today are large, professionalized, and very well-capitalized networks”, ponders Jorge Eduardo Dantas, coordinator of the Indigenous Peoples Front at Greenpeace.

The sale of machinery is one of the blind spots in combating illegal mining, according to the expert. “There is no control. The machines continue to be sold, and people are using this equipment criminally.”

Greenpeace highlights that there are monitoring and remote blocking technologies that could prevent the use of machinery in criminal activities.

An example is the “Consciousness Code” program, which, when inserted into a machine’s onboard computer, emits an alert or even shuts down the vehicle’s engine when it approaches a protected area.

“We started from a very simple insight: if we can’t stop humans from destroying forests, we can stop the machines that do it”, explained Hugo Veiga, global creative director at AKQA, the company that developed the software.

However, the companies’ adoption is timid. “Companies lack a greater commitment to short-term solutions. If the company truly wants to commit to ensuring that its fleet will not cause damage in a protected area, it could implement the code today”.

Itaituba's surroundings on alert, in Pará

In southern Pará, within a radius of 380 kilometers from Itaituba, 34 machines were seized in conservation units along the Tapajós River: in the Alto Maués Ecological Station, in the Jurupari, Crepori, and Amaná National Forests, and in the Tapajós Environmental Protection Area. The latter two were the conservation units with the largest mining areas registered in 2022, according to MapBiomas.

“The Creporizinho River is dead”, laments Finger from Ibama, referring to the river that runs alongside the Tapajós protected area. In addition to the impact on water resources, mining contributes to the advancement of deforestation through the opening of airstrips and access roads to areas of illegal activity.

These conservation units in the Tapajós basin are adjacent to the territories of the Munduruku people. The activity exploded in the region starting in 2017, along with reports of mercury contamination, a substance used to separate gold from impurities.

Repórter Brasil visited villages in the Upper Tapajós region in April of last year and revealed the impacts of mining: children with malformations and developmental delays. In April, the Articulation of Indigenous Peoples of Brazil filed a lawsuit in the Supreme Federal Court to denounce mercury contamination among the Munduruku.

“The contamination is really affecting everyone. Many people are already losing children, or they are born with disabilities because of mercury. We are concerned about future generations”, warns Doto Takak Ire, from the Kabu Institute.

This report was produced with the support of Global Witness.

Leia também