Wearing a red-feathered headdress, torso painted in black swirls, with microphone in hand, chief Juarez Saw made a bold declaration: “The [Brazilian] government is coming here to get rid of everything — the natives, the forest and the river.”

He was addressing 230 Munduruku, Amazonian Indian leaders, who had gathered together on the banks of the Tapajós River’s remote rapids, in the state of Pará, to discuss resistance to a federal government plan to build up to seven hydroelectric projects in the area.

If built, the São Luiz do Tapajós dam — the largest of the seven — would possess a maximum generating capacity of 8,040 megawatts and create an artificial lake covering 72,225 hectares (278 square miles). A portion of that lake would flood Munduruku territory, including the Dace Watpu village, site of the September 2015 meeting. The seven Tapajós Basin dams (three on the Tapajós River and four on its tributary the Jamanxim River) would generate a combined total of 16,152 megawatts of electricity and create reservoirs covering 302,174 hectares (1,162 square miles)

“They want to end the history of the Munduruku, but we won’t let them,” chief Juarez Saw declared. After every pronouncement, his listeners responded with a resounding shout: “Sawé!” — both a salutation and a war cry.

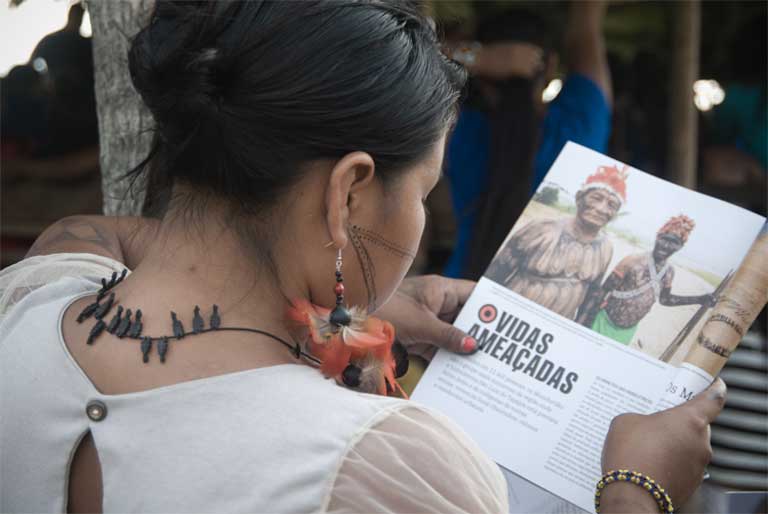

That same war cry rang out in December at the United Nations climate change summit (COP 21) in Paris. This time, a woman was at the microphone, Munduruku native Maria Leusa Kaba, who went to France to receive the Equator Prize. The UN award recognized the indigenous group’s stance against the hydroelectric plants as an action of “outstanding success in promoting local sustainable development.”

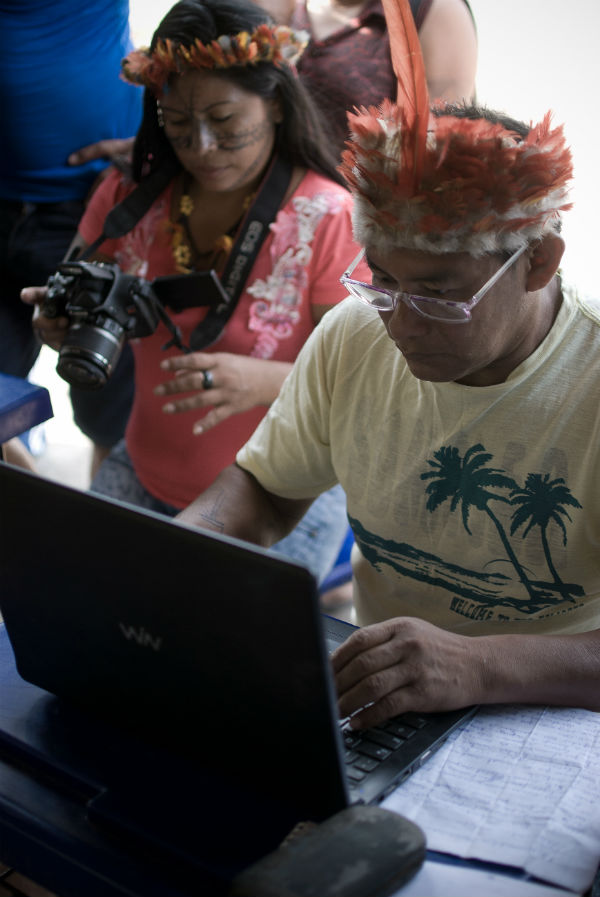

Whether in Pará, Paris or Brasília, the Munduruku have recently demonstrated great skill at political engagement, adroitly making new partnerships, maintaining and strengthening past alliances, and fielding dedicated, well spoken leaders who have studied their rights under Brazilian law, and who are schooled in international mechanisms that can be used in defense of their lands.

This organizational and strategic capacity — though honed to new sharpness in recent months — pre-dates the newest power plant debate, and stems from the Munduruku’s heritage. Traditional Munduruku political rites resemble participatory democracy in its most intimate town meeting style. Anyone — man, woman, young or old — may speak at Munduruku meetings for as long as they like. All decisions must be made by consensus, regardless of how long it takes. During last September’s four-day marathon event, the discussions began at dawn and extended till sunset. A bowl of flour and water was passed around, which attendees sipped to prevent fatigue.

Participants were given the choice of speaking in either Munduruku or Portuguese; though most preferred their native language, and not everything was translated. “Speaking in Munduruku is a way of marking our difference of conducting politics,” explained Munduruku historian Jairo Saw. Journalists and non-indigenous allies who attended and didn’t know the language, listened as borrowed Portuguese terms peppered the discussion, words such as: “scientists, demarcation, blocking, government” and “concern.”

Munduruku attendees also found another way of vividly demonstrating “concern.” Males hefted weapons throughout the event, carrying their bows and arrows as a symbolic reminder of the warrior tradition of aggression and violent resistance for which the indigenous group was renowned in the past, but which they’ve moderated in the present.

From headhunters to political strategists

The Munduruku dominated the Tapajós Basin before the arrival of Portuguese colonizers, waging bloody campaigns against their neighbors, and striking fear into other indigenous groups. “They are considered the most bellicose Amazonian tribe”, explained José Savio Leopoldi, anthropologist at the Federal Fluminense University and an expert in Munduruku history.

The name “Munduruku” was bestowed by rival groups and means red ants, an allusion to the indigenous group’s fierce battle formations. According to historic record, large contingents of warriors staged surprise attacks at dawn, decimating rival adult populations, taking home their enemies’ heads as trophies. The heads were mummified, placed on long spears, and displayed in front of Munduruku villages. The group’s warrior fame spread well beyond the Tapajós Basin, with their homeland known as Mundurkania, and with some of the heads of defeated foes ending up in museum collections in Brazil, England and Portugal.

“The human head symbolized power,” explained Jairo Saw. “Today we are in another era and we fight our battles in other ways, but that warrior spirit is still in us.”

For Tiago Vekho — an anthropologist with the Socio-Environmental Institute who conducts doctoral research on the Munduruku — history helps explain the form that the group’s current resistance is taking. “They had Spartan logic: it was a society focused on war,” he said. “Today, they consider themselves to be at war against the [Brazilian] government and you can see in the village daily life that they are all mobilized for it”.

The Munduruku don’t hesitate to evoke their combative past to sharply punctuate their views regarding the present dam dispute, which they see as a government-sponsored invasion. Their warriors have, for example, marked the self-demarcation boundaries of Sawré Muybu Indigenous Lands with signs that include graphic drawings of mummified heads — a notice to anyone who would enter areas inhabited by the Munduruku.

These traditional self-demarcation boundaries are considered by the Munduruku to be one of their most important strategic lines of resistance against the hydroelectric dams and reservoirs. The National Indian Foundation (Funai) — the Brazilian government body chartered with establishing and carrying out indigenous policy — has delayed recognition of the Sawré Muybu Indigenous Lands, causing the Munduruku to lose patience with the Funai process. In defiance, the group occupied Funai´s local office twice, but the action had no concrete consequence. They also wielded machetes and dug trenches along the border.

In reaction to questions sent by Repórter Brasil, Funai´s press department issued a statement saying that the indigenous lands recognition report has not yet been published due to two official disputes: one filed by the Mines and Energy Ministry and the other by the Environment Ministry, which are now under evaluation. “After this stage, the [recognition] report will be forwarded to Funai´s presidency for the president´s consideration and signature”.

The Sawré Muybu border entrenchment was not a local action. The Munduruku are one of the largest indigenous groups in Brazil, numbering over 13,000. When a community or group of communities is locally threatened, others lend support. During the self-demarcation show of strength, for example, warriors travelled up to three days to help those directly threatened by the dams to dig the trenches.

“We live in a traditional area, left to us by our ancestors,” said Jairo Saw. “Since the land is ours, we decided to stop waiting for the [Brazilian] government and we [claimed] it ourselves.”

The ability to resist and adapt under pressure is another Munduruku historical constant. In the early 19th Century, the Portuguese signed a treaty with the group to curb conflict. When Catholic missionaries arrived with the idea of catechizing and “civilizing”, many Munduruku were banned from speaking their native language or practicing traditional rites. In opposition, the indigenous group worked cohesively to preserve its traditions, while simultaneously reinventing their culture to survive and stave off domination.

Although Catholic practices like baptism were absorbed, the Munduruku maintained faith in ancient rites, the power of shamans and their God Karosakaybu. “They never had an institutional religion. It was a cosmology that ended up taking in the idea of a Christian God”, explained Tiago Vekho. Despite decades-long missionary prohibitions, the Munduruku language survived, and today is the population’s most spoken tongue. The majority of women and children do not speak Portuguese.

Resistance to the Brazilian government is nothing new for the group. The clear demarcation of Munduruku Indigenous Land, which spans the northern part of the Tapajós Basin, first originated with the group’s desire to prevent modern incursions. The process began in 1975 and has been a long ordeal during which the Munduruku honed their skills at writing letters to the Brazilian government and building a political movement.

Jairo Saw was just a child back then, but he remembers adults from various villages gathering to create and debate effective demarcation legal strategies in the 1970’s. Today, he is one of the Munduruku’s many representatives who travel to Brasília and abroad to state the group’s case against the dams before government bodies and at UN conferences. The Munduruku have also regularly provided the Federal Attorney General’s Office with information so that it can take legal action against the proposed power plants.

Fighting dams, forming alliances

The Munduruku have gained plenty of experience fighting dams in the past few years. In 2010, the Brazilian government succeeded in moving ahead on the gigantic Belo Monte dam, which the Munduruku strongly opposed. They and other indigenous demonstrators repeatedly occupied the Belo Monte dam site at Pimental in 2012 and 2013, paralyzing construction work. The dam was completed in 2015, but litigation has prevented it so far from going into operation.

The Belo Monte experience served as an important lesson in knowing how not to act against such projects in future, lessons that may now benefit efforts to defeat the Tapajós power plants. “The Xingu indigenous group lost out against the government [because] there were many different indigenous groups, some co-opted, and they ended up divided. This served to show us how we need to be united to strengthen our fight,” said Jairo Saw.

The Munduruku in the Tapajós Basin are now working to build trust and nurture alliances among a variety of parties, including other indigenous groups, the quilombola — Amazonian descendants of fugitive slaves — local riverine communities, sympathetic city-dwellers, and environmental organizations. “Our struggles must happen together,” stated Jairo Saw.

The breadth of this alliance was visible at last year’s strategy meeting on the Mid-Tapajós. More than 20 local, plus more remote, Munduruku leaders attended, along with leaders from other ethnicities and riverine communities whose constituents would be impacted by the dams. Also present were representatives of the Federal Attorney General’s Office in Pará, which has prosecuted 19 legal cases against the government and companies for violating the rights of local indigenous and riverine groups. Also there were representatives from more than ten non-profit organizations, such as Cimi, the Indigenous Missionary Council, Greenpeace and FAOR, the Eastern Amazon Forum.

“The Munduruku are a highly-politicized group. They understood that there was no way to fight the governmental machine without the support of the Brazilian society, and that the NGOs fulfill the role of making this connection,” said Danicley de Aguiar of Greenpeace.

The Munduruku plan to grow their alliances further. They’ve gone to Brasilia numerous times to protest governmental measures affecting indigenous rights, and to foster relationships with likely new partners. Their most recent trip was motivated by PEC 215, which confers the Legislative branch of the federal government with the power to draw new indigenous territory boundaries.

“We know that putting this decision in the hands of the rural production sector lobby will make the situation even more difficult for us and our kin,” explained Rozeninho Saw Munduruku, president of the Association Pariri that represents seven indigenous villages.

River economy vs. money economy

A native Munduruku will watch rising and falling river levels with the same attention that an economist tracks inflation or an investor follows the stock market. That’s because the river forms the basis for the group’s survival: fish provide their primary source of food, followed by game, foraging, and small farming. All of these livelihoods depend on the health of the forest, which in turn depends on the health of the river.

The Munduruku therefore see the dramatic ecological changes that the proposed Tapajós dams would bring as equivalent to a complete economic collapse. “We know that [the dams’] construction will change everything. With the end of the high-water cycle of the river, the trees along the banks will dry up and the fish will no longer find their food,” asserted Jairo Saw. Then the fish will die.

Scientists who have closely studied dams elsewhere in the Brazilian Amazon have identified environmental impacts similar to the effects predicted by Jairo Saw. One such effect is the loss of the “varzea forest”, vegetation that grows along riverbanks and is adapted to being submerged periodically each year. “This forest is not adapted to being underwater year round, and dies when permanently flooded by a reservoir”, writes Philip Fearnside, a research professor at the National Institute for Research in Amazonia (INPA) in the article “Impacts of Brazil´s Madeira River Dams: Unlearned lessons for hydroelectric development in Amazonia”. Fearnside observed that in the case of the Madeira River dams, varzea forest vegetation died out after permanent flooding and rotted underwater, a phenomenon that, according to him, could have contributed to the death of the river’s fish.

“I had to study a lot to reach the same conclusion,” said Jansen Zuanon, a biologist with the National Institute of Amazonian Research. Invited to exchange knowledge with indigenous groups, he was one of the researchers hired by Greenpeace to conduct a series of analyses questioning the Brazilian government-commissioned Environmental Impact Study (EIS) for the Tapajós dams.

The official EIS, still under analysis by Ibama, the Brazilian Institute of Environmental and Renewable Resources, concludes that the dams’ impact on local biodiversity would be acceptable. Whereas the analysis commissioned by Greenpeace, and carried out by respected institutions like the Federal University of Pernambuco and the National Institute of Amazonian Research, concluded that the hydroelectric dams and reservoirs would endanger ecosystems and threaten the survival of fish, birds and plants. The non-governmental analysis pointed out fundamental problems with the EIS methodology, data analysis, and plant and animal inventories; it urged that the official study be rejected.

The group responsible for producing the official EIS, the Tapajós Study Group, is made up of nine private and state companies involved in the Tapajós dams, including Eletrobras and CEMIG, two large Brazilian electrical utilities, and Camargo Corrêa, a huge Brazilian construction company — entities that could stand to gain financially from the projects. In a written response to questions regarding this article, the Tapajós Study Group stated that it was holding meetings with Ibama to investigate the report more deeply. Only after that investigation will the organizational body issue its final version.

“It is worth emphasizing that the Tapajós River power plants will guarantee safe provision of clean and renewable energy,” wrote the Tapajós Study Group in its response to Repórter Brasil. “They also will benefit the local population, by providing jobs and income, allowing for the economic and social development of this region of the country.”

So far, the Munduruku and their allies, along with Brazil’s Federal Public Prosecutor, see themselves as successful in presenting strong arguments questioning the Tapajós project, and in slowing its progress. The concession auction for the São Luiz do Tapajós power plant (in which companies will compete for the right to build the dam and sell much of its power), was slated for 2014, then 2015, and is now delayed for the second half of 2016. In June, 2015, the president of the Energy Research Company (EPE) — Brazil’s federal energy planning company —recognized environmental issues as a licensing obstacle.

The Munduruku take offense when Brazilian government representatives argue that the construction project will generate economic growth. They say they’ve grown tired of explaining that certain types of wealth — particularly those valued by the Munduruku — cannot be measured in money.

“There are ‘writings’ all along the Tapajós River, on its body, on the trees and rocks that speak to us,” said Jairo Saw. “The white man can’t manage to read it, but our shamans can, because they see it with a spiritual eye. All of it is sacred, it is a part of who we are, and should be respected,”

“No amount of money can buy this,” said Maria Leusa “We cannot sell one drop, one stone. There is no negotiation.”