The Triunfo do Xingu Environmental Protection Area (EPA), in southern Pará state, appears at the top of several lists of conservation units (CUs) with the highest rates of deforestation and fires not only in the Amazon, but in Brazil as a whole. That is a known fact. Over more than a decade, the region has been coveted, invaded and plundered by numerous “profitable” enterprises seeking to dominate the territory, which resulted in several conflicts and repeated reports of crimes rarely solved by inspection operations. They might include environmental violations per se or other crimes such as land grabbing or exploitation of slave-like labour.

As its name entails, this vast 1.68-million-hectare territory located in a strategic position in the so-called Xingu Socio-Environmental Diversity Corridor is supposed be an environmental protection area. This category was created by Law 6902/1981 and is part of the National System of Conservation Units (SNUC) (Law 9985/2000). It is aimed precisely at protecting biological diversity, regulating the occupation process and ensuring sustainable use of natural resources in areas with some degree of intervention and presence of outside actors. That is what it should be.

Instead, the EPA Triunfo do Xingu has been invaded, fragmented and eaten away by activities with wide-ranging impacts such as illegal mining, logging and livestock. With about 1.68 million hectares, it was created by a state executive order in 2006, and it covers parts of the huge municipalities of São Félix do Xingu (66% of the EPA’s total area) and Altamira (34%). It is part of the Amazon Region Protected Areas Program (ARPA), together with neighbouring areas such as Terra do Meio Ecological Station and Serra do Pardo National Park. Creation of Conservation Units and demarcation of Indigenous Lands (ILs) between 2004 and 2008 were also part of the Action Plan for Prevention and Control of Deforestation in the Amazon (PPCDAm, in its Portuguese acronym). According to a study by the Amazon Environmental Research Institute (Ipam) , it helped to reduce deforestation rates during that period by 37%.

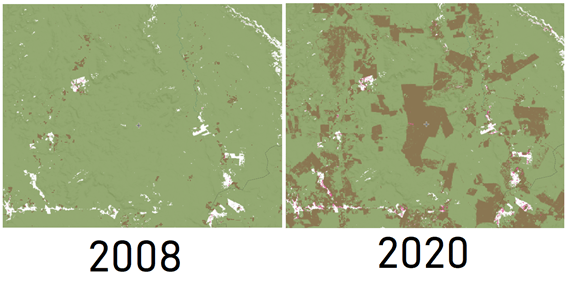

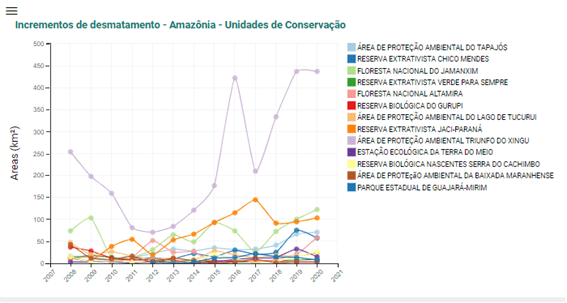

However, the most recent data are frightful. Between 2018 and 2020, more than 2,000 trees were cut down per hour just in this Conservation Unit, according to a survey conducted on Sirad X’s three-year monitoring. Sirad X is a deforestation detection system managed by Rede Xingu+, a civil society network that brings together organizations, associations and institutions working in the Xingu River basin. Approximately 93,300 hectares were deforested in the same period in the Triunfo do Xingu EPA, which accounted for nearly one fifth (18%) of all deforestation in the basin.

According to the same survey, two-fifths (40%) of the territory previously covered by native forests have already been converted to other uses, in particular bovine cattle raising. In 2015, this figure was 27% – a 13% increase in just five years. The municipality of São Félix do Xingu is known for having the largest number of cattle in the country – an estimated 2.3 million, according to the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE) – while Altamira has over 700,000 cattle head. Fifteen years after its creation, the Triunfo do Xingu EPA has no consolidated management plan or zoning. Management Council meetings have become virtually annual (the last one with a registered minute took place in May 2019, and the second-to-last meeting was held a year earlier, in May 2018), according to the website of the Pará State Forest and Biodiversity Institute (Ideflor-Bio).

In September 2020, the Pará state government’s website released news about developments in its “Sustainable Territories” Program, based on a public notice for selection of producers to receive special government assistance, presented as a pillar of the Amazônia Agora strategy. It includes Ideflor-Bio and the State Environment and Sustainability Department (Semas), among other agencies active in the EPA. The municipal government of São Félix do Xingu also highlighted the initiative aimed to list and support “good practices.” The press offices of Ideflor-Bio and Semas were asked about their stances on both the progress and the intensity of destruction within the Conservation Unit in its various aspects and on ongoing government actions, but they did not respond.

According to Elis Araújo, a lawyer from the Socio-Environmental Institute (ISA), “there is major land grabbing in the Triunfo do Xingu EPA. Large companies and cattle ranchers are pushing for more land. There are conflicts over resources, including access to water, to rivers. And the area has never had a management plan. Conflicts have never been solved.” In June 2020, due to the alarming increase in deforestation reports by the various monitoring systems, social organizations that work in the area – ISA, Rede Xingu+, Greenpeace Brazil, International Institute of Education of Brazil (IEB), Institute of Forest and Agricultural Management and Certification (Imaflora) and the Amazon Institute for Man and Environment (Imazon) – submitted a complaint to the Federal Prosecution Service (MPF), the Pará State Prosecution Service (MP/PA), the National Council of the Prosecution Service (CNMP) and the state government demanding urgent measures to stop the escalation of destruction. They recommended that actions be taken “promptly” to “combat criminal organizations that fund and encourage people to invade protected areas, explore logging and open new mining sites,” mentioning “local politicians who demand that people transfer their electoral registrations so they can vote in the next municipal elections,” as described by the press, and asking for “improvement in the work of institutions directly involved in combating environmental crimes associated with deforestation.”

“Consortia of deception”

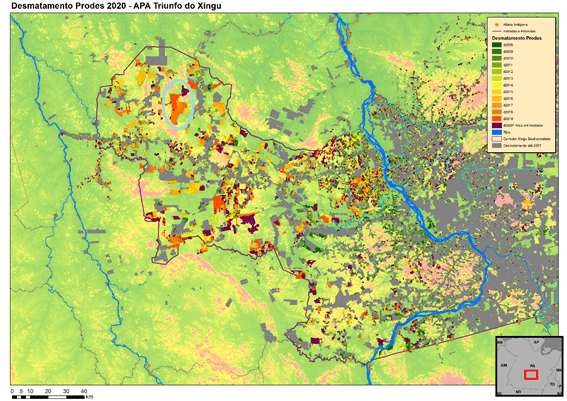

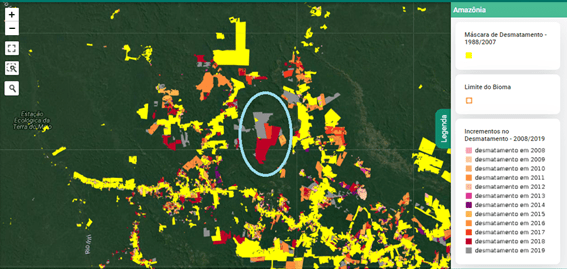

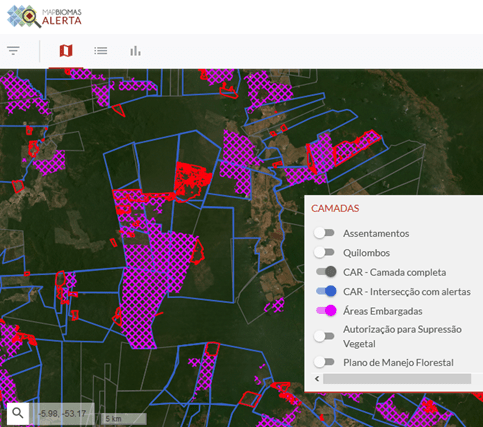

Based on our own findings and comprehensive data crossing – including satellite images and monitoring systems, land tenure documents available on the Rural Environmental Register (CAR), as well as records of public civil actions and lawsuits, or information about supply chains (commercial connections), we looked into the functioning of the “consortia of deception – groups of agents that are behind this “steamroller” of socio-environmental destruction that is still in full operation. By focusing on a degraded area full of environmental violations and interdictions on the north of the Triunfo do Xingu EPA (see map above, highlighted in blue), with strong influence on the increase of deforestation and fire in the fully protected area of Serra do Pardo National Park, it was possible to establish an overview for the second part of the series on the “tricks” that sustain socio-environmental devastation schemes in the Amazon (see the first part of the series here.

In the first three months of 2021, monitoring by Imazon (SAD) and MapBiomas Alerts confirmed the existence of multiple clear-cut deforestation zones within the Conservation Unit, including in the area highlighted above – a group of allegedly large contiguous properties with high concentration of interdictions for environmental violations determined by the Brazilian Institute of Environment and Renewable Natural Resources (Ibama). This portion of the Triunfo do Xingu EPA was also full of – constantly fragmented – registrations on the Rural Environmental Register (CAR) and some land titles from the Land Management System (SIGEF) developed and maintained by the National Institute of Colonization and Agrarian Reform (Incra). Its location is strategic for establishing bases within the area and also for intensifying fronts to invade other, more preserved and more restricted conservation areas such as the already mentioned Terra do Meio Ecological Station and Serra do Pardo National Park.

By using the history of occurrences and several cross-searches and by focusing the analysis of deforestation dynamics on this specific portion of the EPA, it was possible to understand the underlying dynamics and processes of forest destruction that threatens the Xingu Corridor, formed by nine Conservation Units and 21 Indigenous Lands (ILs) that span 26 million hectares.

That remote area (about 240 km from the urban centre of São Félix do Xingu) is located between two side roads – Toca do Sapo and Jabá, within the EPA, both leading to the Pardo River and at the boundaries of Terra do Meio and Serra do Pardo. It is formed by a group of large properties, with many subdivisions and overlapping CAR registrations. Within this zone of widespread devastation, four properties have their land titles registered at Incra to Caio Jerônimo da Silva (Brumado, Brumado I, Colorado do Rio Pardo and Limoeiro farms). He is the son of Coriolano Rodrigues da Silva, and both are on Ibama’s interdiction list. Coriolano, in turn, appears as the owner of two other areas in the region also known as “Gleba Rio Pardo” according to the CAR: the Dois Irmãos Farm and the Esplanada Farm, registered to Agropastoril Três Lagoas, a company belonging to Coriolano Rodrigues da Silva, registered as an eyeglass store (inactive) in São Miguel do Araguaia, Goiás.

Only for one of the violations, Caio was fined R$ 48.1 million in November 2018, for destructing 4,800 hectares in the region (part of the area shown as lilac squares on the map above, with the area registered on the CAR shown as a squarer shape on the right, precisely at the Brumado Farm). In one of the Public Civil Actions filed by the Federal Prosecution Service (MPF) on Federal Courts against Coriolano after deforestation was found in a nearby area – as part of its Amazon Protege program –, he claimed that he had already been fined by Sema, then he said that he had not been properly served and, finally, that the violations had not been confirmed and the area in question did not belong to him. To obtain proof of the last statement, Judge Maria Carolina Valente do Carmo had required an expert assessment, but the defendant himself chose not to deposit the fees to pay for it. The sentence, handed down in April, partially accepted the Prosecutors’ arguments, recognizing the defendant’s responsibility. While the Judge did not rule that he should pay the R$ 19.1 million compensation initially requested, she ended up ordering Coriolano to reforest the area using a professional and detailed project and pay R$ 598,000 as collective moral damages to the Diffuse Rights Fund.

“Holes”, deviations and connections

In order to avoid restrictions and constraints imposed by environmental interdictions, violations and fines, families’ members not changes places with and replace each other, but also resort to a series of other figureheads who lend their names so those family members do not appear ahead of the entire group of enterprises.

This procedure has been denounced for years by organizations such as Greenpeace, which recently highlighted another similar case involving about 5,300 hectares deforested between August 2019 and June 2020 on a farm further south in the same Triunfo do Xingu EPA. The total area of the Tiborna Farm was “dismembered” into fragmented CAR registrations on behalf of“third parties”. Through another “clean” farm, the property guaranteed the “regularity” of its bovine livestock production. The case had already been mentioned in a report on squatters, loggers and episodes of violence at the18-year-old Terra do Meio (Pará: Conflict status).

In the case of the Rodrigues da Silva family, at least four other “owners” are listed on CAR documents (most of them with pending registration, but some were even “active,” that is, officially validated by the state agency). Kaio Fontes Moura appears to have the closest ties to the family, since he is also the apparent “owner” of an area (Bela Vista Confinamentos) closer to São Félix do Xingu, used by the family as a support point for their cattle business. In reality, analyses of the supply chain show that the cattle come from the aforementioned Colorado do Rio Pardo Farm, on the way between the region furthest to the north of the protection area and the urban centre, where slaughterhouses and the road for transportation are located.

Another property (São Matheus III Farm) is registered to Kaio in an area further south of the municipality, where some other nearby farms belonging to the group are concentrated (on the edges of the Menkragnoti Indigenous Land), which join two other main farms in terms of cattle trade. All beef cattle is traded through the São Matheus and São Matheus II farms, registered on the CAR to Caio Jerônimo. Animals from areas far from the Triunfo do Xingu EPA are transferred (sometimes in the opposite direction as well, for fattening purposes) to the intermediate area of the São Matheus Farms (I and II) and sold to meatpackers such as giant JBS unit in Tucumã, according to a supply chain flow analysis made with documents issued in 2018. In a statement, JBS informs that Fazenda São Matheus II was registered as a company supplier, but has been blocked since 2019; and that São Matheus I is not a supplier.

The cases of Coriolano and Caio has yet another partner – farmer Manoel Carmo da Silva. He appears as a partner of the family in public civil actions filed by the Federal Prosecution Service and has ties with companies registered on Brazil’s National Corporations’ Register (CNPJ): one on Coriolano’s name and another one on behalf of Agropastoril, which sometimes also appears as Agropecuária Três Lagoas.

Repórter Brasil found that Caio Jerônimo, a well-known producer in São Félix do Xingu, was murdered a few months ago in the region itself; the reporter tried to contact the other farmers and the respective lawyers, over the first 10 days of May, but failed. In case of any claim, this report will be updated.

An analysis of the supply chain also shows intense flow from Coriolano’s and Caio’s farms to another kinship-based conglomerate: that of the Bueno family. Even due to the proximity of one of the farms belonging to Valdiron Aparecido Bueno (Três Poderes Farm, later an intermediate “supplier” to another property, the Sossego Farm), they have connections similar to inter-family “consortia”. By phone, he claims to even be renting pasture areas at Três Poderes (“because it’s cheaper”) to “neighboring” third parties and denies that he has made these “circulations” of animals with the farmers described above. He only confirms that he had Caio Jerônimo as his client in the agricultural store that he keeps in the center of São Félix do Xingu. “You see the people talking about deforestation, but when we walk along the side of the roads – and I was there for about four months because my job has been mostly in the city – you don’t see anything. I border the property of Caio Jerônimo’s family, but I never went there to see how it is. I know that my share is in the woods ”.

In addition to being a producer, Valdiron is also a trader and organizer of livestock events in São Félix do Xingu. He was interviewed about the social context for livestock predominance in the town for the investigative report published in July 2019 by Repórter Brasil in partnership with English newspaper “The Guardian” and the “Bureau of Investigative Journalism” about the repeated purchase of cattle from an illegally deforested and interdicted area.

Buffer zone

Another farmer linked to the same region highlighted in the Northern part of the EPA is Wilson José Mendanha, pointed out in a lawsuit filed by the Pará State Prosecution Service (MP/PA) as responsible for the Chopp Dance Farm, which is part of the conglomerate of properties highlighted here (in circles on the maps above). Mendanha appealed the first-level court decision that had frozen R$ 22.7 million of his assets and ordered immediate interruption of any degrading activity on the site (under penalty of a daily fine of R$ 2,000) for deforesting 2,000 hectares found by an Ibama operation in June 2019. In the appeal, he tried to justify himself by saying that he had sold the property to another person in 2016 and that it was registered to a third party on the CAR, also since 2016. Due to insufficient documentary evidence, none of the justifications was accepted by Court of Appeals Judge Diracy Nunes Alves of the Pará Court of Justice in a decision published on April 13, 2021.

The sentence concerns a single property of 4,100 hectares which, in the Rural Environmental Register System (SICAR) in Pará, appears to be divided into three areas (Chopp Dance I, II and III). What the Judge saw in the case of the huge deforestation of more than 2,000 hectares attributed to Mendanha was “the so-called periculum in mora in reverse, that is, when the danger of delay lies at the other party of the legal/procedural relationship,” since “there is risk of damage to the community if the ecologically balanced environment is not restored (Art. 225 of the Constitution).” “The fine has an individual nature and should be applied to the offender. Since fumus boni iuris [plausibility] and periculum in mora in favour of the appellant has not been demonstrated, the fine cannot be annulled, as there is no evidence that the property belongs to a third party, just as the causal link was not interrupted,” she adds.

Mendanha’s son Emerson José is one of the people involved in another public civil action filed by the Federal Prosecution Service for illegal deforestation in the same area north of the Triunfo do Xingu EPA (highlighted on the maps above), confirmed by data from the PRODES system, from the National Institute of Space Research (Inpe), as part of program Amazon Protege. The same Public Civil Action involves not only Caio Jerônimo and Kaio Fontes but also a farmer responsible for deforesting more than 3,200 hectares (detected in 2017) at the Santa Rosa farm (total area 6,800 hectares) and also charged by Sema with a series of other environmental violations.

Repórter Brasil reached out to Wilson and Emerson Mendanha, by telephone. Emerson said he is unaware of the MPF’s lawsuit. Wilson said what he had already claimed to the court. He explained that he had sold the land years ago and that, when he owned the area, “he did not remove a single tree from the site”. The responsibility, therefore, would lie with the buyer, named Leonardo, and of whom he does not remember the surname. Wilson still claims that he continues to try, via court, to transfer the responsibility to who would be the current owner of the land.

Combating the continuity and accumulation of irregularities is at the heart of the group of NGOs’ alerts and recommendations to the authorities regarding the EPA. In addition to demanding continuous inspection operations and the establishment of two bases within the conservation unit by the Pará state government, they suggested a “buffer zone” in a 10 km strip around its boundaries with federal protected areas. “The very management plans for federal conservation units such as the Serra do Pardo National Park and the Terra do Meio Ecological Station expressly mention the Triunfo do Xingu EPA. Therefore, no buffer zone would be needed between the more restrictive federal areas and this state area,” says Elis Araújo from ISA. “But what we see is the need to restrict activities that can be developed in this closer area [between the state conservation units and federal units]. The EPA is not taken seriously and doesn’t have effective management, and so it ends up not being an actual conservation unit.”

At least according to some members of Ideflor-Bio in their dialogue with these organizations, stronger initiatives such as the establishment of a “buffer zone” do not find support in the state government, which prefers focused initiatives such as “Sustainable Territories.” Meanwhile, media reports and academic research in the area of livestock farming increasingly add information about the means used by producers to continue devastating. In an article published in 2020, researchers from Imazon and the US-based universities of Florida and Wisconsin-Madison pointed out five ways in which producers with farms marked by socio-environmental problems trade their cattle: a) selling it as “standing cattle”, directing animals to specific areas where they remain in quarantine; b) transferring it to neighbouring states with weaker monitoring or to meatpackers that do not enforce requirements; c) transporting it to “clean” properties belonging to others to use them as references of origin; d) leasing “regularized” land to do the “washing” by themselves, or e) trading it with intermediaries from farms that will resell the cattle later.

The need to extend monitoring systems – such as the Meat Conduct Adjustment Agreement (TAC) headed by the Federal Prosecution Service – at least to a first tier of “indirect suppliers” is one of the points highlighted by the study, which include broad desktop research and work with ranchers. But an aspect that still gets little attention in these surveys – and which emerged from the crossing of data and findings from this devastated region in the northern part of the Triunfo do Xingu EPA – is the participation not only of some technicians and specific networks helping these “consortia of deception,” but also of state agents.

These points of contact for large private farmers with public servants “infiltrated” in state agencies at various government levels (which will also be mentioned in the third part of this “tricks” series) have their roots in historical processes, according to experts interviewed by Repórter Brasil. They go back decades in this region that became known as Terra do Meio. Tarcísio Feitosa, an environmental activist with a wide range of activities in the Xingu region, points out that this logic of “consortia” underlying several types of crimes combined (in addition to land grabbing, logging, livestock and illegal mining, there are others such as money laundering) has existed for a long time, with strong political and economic connections. The countless denunciations and investigations involving, for example, public servants of the National Institute of Colonization and Agrarian Reform (Incra), including recent convictions, point in the same direction.

When the mosaic of Conservation Units and Indigenous Lands of the Xingu Corridor was established in mid-2000 as a result of social pressure after the murder of environmentalist catholic nun Dorothy Stang in 2005, many of those “consortia” that were dispersed in different expansion fronts for vegetal and mineral extraction and agriculture frontiers in the Amazon started concentrating on the Triunfo do Xingu EPA. “The Triunfo do Xingu EPA was the result of strong negotiation with the state government, following the idea that ‘people are investing lots of money and you can’t stop deforestation,’” adds Feitosa, who actively participated in these processes by coordinating mobilization of local communities and was awarded in 2006 with the Goldman Environment Award for South and Central America.

“They knew about this dynamic that was taking place in the region, including the intention to keep advancing with cattle. If you look at charts of livestock displacement and increase, this is very visible,” he adds. Also as a result of these “consortia”, inspection is minimal: from combating slave labour to environmental issues. Criticising the relationship between CAR registrations and legalization of land grabbing, Feitosa, after many years and several projects across the region, makes a harsh and gloomy forecast.

“This region of the Triunfo do Xingu EPA will be consumed by fire. Perhaps only forests within legal reserves will be left, and they are extremely impoverished because they have already been exploited in years of logging, and maybe the EPA [Environmental Protection Area] – if there is an EPA and it is respected. But a lot of things will still burn in there this year [2021]. Watch and see: a lot of things will burn.”

Alert from the editor: this article was updated, with addenda and adjustments, on 05/11/2021.