To benefit ranchers, Rondônia state representatives passed a law that decimates two reserve areas around Porto Velho, the state’s capital. The environmental damage, if the bill is sanctioned by the governor, will be the removal of the environmental protection of 219 thousand hectares from the Jaci-Paraná Extractive Reserve and the Guajará-Mirim State Park, an area slightly bigger than those of the cities of London and Madrid combined.

Almost half (11 out of 25) state legislators who unanimously approved the project are cattle ranchers or were financed by cattle ranchers, according to a data crossover carried out by Repórter Brasil agency, based on the declaration of assets and donors available at the Superior Electoral Court with documentation on livestock transport. The reduction of the areas of environmental protection will directly benefit this economic activity: it is estimated that there are 120 thousand head of cattle in Jaci-Paraná reserve.

Among the 25 state representatives, six received ranchers’ donations in the last electoral campaign: Alex Redano (DEM party), Cássia das Muletas (Pode), Geraldo da Rondônia (PSC), Johny da Paixão (PRB), Lebrão (MDB) and Luizinho da Fetagro (PT). In addition to receiving donations, the PT representative is also among the six who are cattle ranchers, alongside Adelino Follador (DEM), Edson Martins (MDB), Ezequiel Neiva (PTB), Luizinho Goebbel (PV) and Laerte Gomes (PSDB).

The relationship of the state legislators with interests in agribusiness is not limited to donations. The bill’s rapporteur, representative Jean Oliveira (MDB party), has no rural property in his name and has not received donations from ranchers, but he is investigated by the Federal Police for being part of a gang that tried to perform land grabbing in a conservation unit and for considering killing a prosecutor who opposed the theft of public land, according to Folha de São Paulo newspaper.

If agribusiness sector is benefited on the one hand, on the other, the project threatens indigenous people, including at least six groups living in voluntary isolation, according to nun Laura Vicuña, a missionary from the Indigenous Missionary Council (Cimi). “If this bill is sanctioned by the governor, Brazil can commit ethnocide,” she says.

Both the Guajará-Mirim State Park and the Jaci-Paraná Extractive Reserve are in areas around the Uru-eu-wau-wau, Karipuna, Igarapé Lage, Igarapé Ribeirão and Karitiana Indigenous Lands. A region that Vicuña defines as an “ecological mosaic through which people in voluntary isolation roam”.

“They [indigenous] have no contact with society and are not restricted to demarcated indigenous lands, therefore, the importance of these reserve areas”, explains Vicuña. According to Cimi, there are four isolated groups identified close to the Uru-eu-wau-wau Indigenous Land, one in the Karipuna and the other in the Karitiana Indigenous Land. “We only know the existence of these peoples from traces found by residents or from overflights”, says the missionary.

The favoring of ranchers to the detriment of environmental preservation and protection of indigenous people is at the origin of the text of the Complementary Bill 80 of 2020, which was sent by Governor Colonel Marcos Rocha to the state representatives. The governor, who is a close ally of Bolsonaro, and reproduces the president’s anti-environmental speech, argued in the text that in Jaci-Paraná reserve there are 120,000 head of cattle “without any environmental licensing or authorization to suppress native vegetation”.

Rocha also assumed the government’s inability to deal with the invasions: “The countless command and control actions carried out so far have been insufficient to prevent the advance of illegal occupation and deforestation.”

It is now up to the governor to sanction or veto the bill sent by himself. The legal deadline ends on Thursday (May 20). A day earlier, the State General Attorney’s Office (PGE) of Rondônia state issued an opinion that points out the project’s unconstitutionality. Among the problems listed by PGE are the absence of technical studies to support the decision and the violation of the principle that forbids environmental setbacks.

Legalization of land grabbing

“The purpose of this law is to legalize land grabbing,” says environmentalist Edjales Brito, a member of the Kanindé Ethno-Environmental Defense Association. For Brito, the government’s justification that it is no longer able to prevent the invasion of areas by livestock is absurd. “They didn’t even consider changing the type of protection in the areas and making it more compatible with the presence of some activities, because the plan is to end everything,” he says.

Brito thinks that Rondônia is a “Brazil’s lab”, in which environmental setbacks arrive first. “The mentality of those in power is colonizing. They call indigenous and extractives lazy and put themselves as the productive sector, with a speech of superiority”, says the environmentalist.

With the reduction of reserve areas, what will happen, according to Brito, is the repetition of a cycle of destruction. “First they remove the wood, then they burn, they make the pastures and, finally, they make room for export monocultures, such as corn and soybeans”, he explains.

The wildfires do not wait for the approval of the law to start the destruction. There were 895 fire outbreaks in the Jaci-Paraná reserve and 133 outbreaks in the Guajará Mirim Park in 2020. The two threatened areas are mostly inserted in the limits of Porto Velho and Nova Mamoré. Precisely the two most burned cities in Rondônia in 2020, as shown by the satellites of the National Institute for Space Research (Inpe).

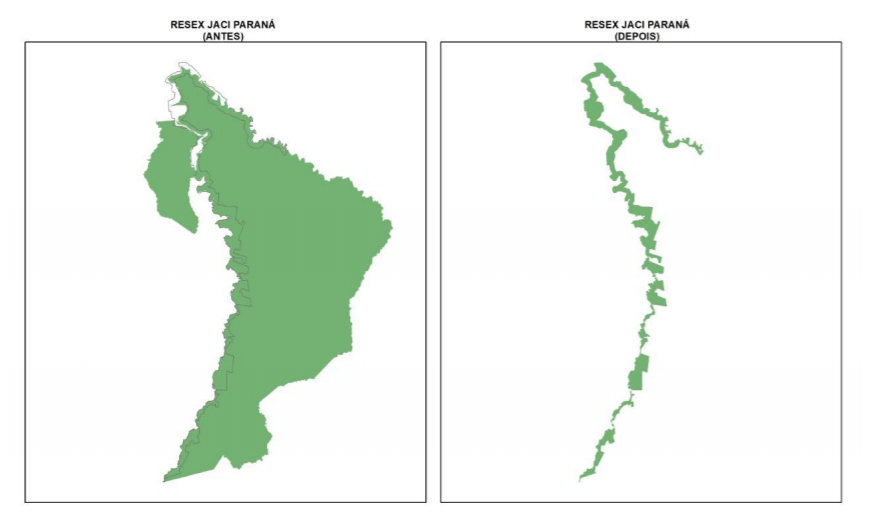

Should the law be enacted, Jaci-Paraná reserve will lose 171 thousand hectares of the protected area, remaining with only 22 thousand hectares, just over 10% of its original area. The area was created in 1996 to settle 52 extractive families that were already in the region, explains the representative of the Organization of Rubber Tappers of Rondônia (OSR), Joadir Lima.

Over the years, with the lack of supervision and support from government agencies, the reserve was being invaded by ranchers. “The rubber tappers always denounced it, but the government never acted, and the families were expelled,” says Lima. Between 2008 and 2020, deforestation in the reserve was 83 thousand hectares, that is, 42% of the total area, according to data from Inpe. It is the second most devastated protected area in the Amazon, behind the Triunfo do Xingu Protection Area, in São Félix do Xingu, in Pará state, another region dominated by livestock.

The modus operandi of the invasion, according to the rubber tapper’s representative, is the entry of people who occupy the land as “stooges” of large landowners. “The advance of livestock and soy in Rondônia is very large and puts pressure on these areas”, says Lima.

Environmentalist Edjales Brito explains that those who invaded the area are not poor people with the profile to be included in agrarian reform programs. “Porto Velho’s farmers have the largest herd in Rondônia and a large part of it is found on these illegally opened pastures in invaded public areas,” he says.

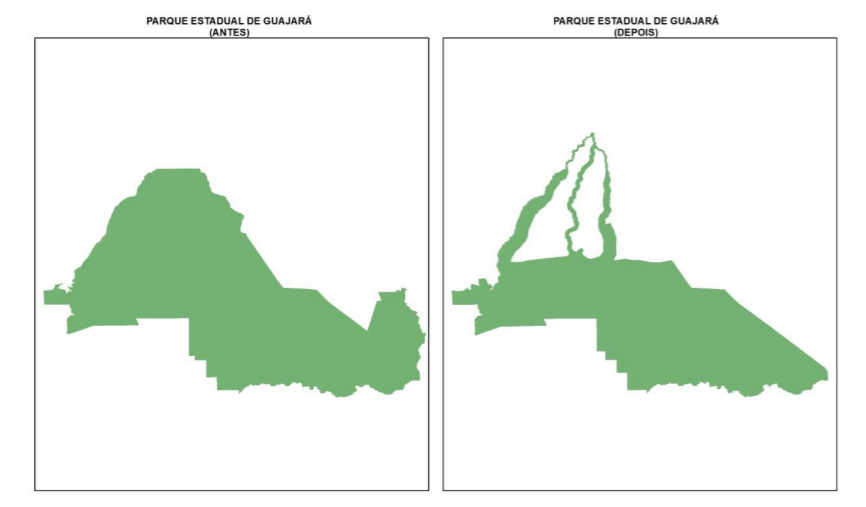

The Guajará-Mirim State Park, which has 217 thousand hectares, will keep 166 thousand hectares, if the project is sanctioned.

Livestock’s Lobby

Brito and Lima are part of a Broad Front for the Defense of Protected Areas in Rondônia, a social movement made up of 65 organizations. The Front tries to oppose the agribusiness lobby, but has failed to convince any of Rondônia’s 25 state representatives to support them.

Repórter Brasil approached the 11 parliamentarians questioning whether there was a conflict of interest because they were rural producers or because they were financed by ranchers. Only Congresswoman Cássia das Muletas (Podemos party) responded. “These are areas that have been occupied for more than a decade by small producers who lived in absolute legal uncertainty due to the irregular condition they were in,” she says.

The state representative also guarantees that the fact of having received a donation from a rancher did not influence her decision, since, according to her, the donor’s properties are far from the preservation areas affected by the bill. She also pointed out that the project foresees the creation of new reserve areas.

Indeed, there are five predicted areas, which add up to 120 thousand hectares, but which according to the opinion of the State General Attorney’s Office are regions “substantially inferior in extension to the dismantled ones, in addition to not reproducing the unique attributes found in the Jaci-Paraná Extractive Reserve and the Guajará-Mirim State Park”.

PGE makes it clear that there is no way to compare the new areas that will be created with the two that may lose protection, as the Jaci-Paraná Extractive Reserve and Guajará-Mirim State Park “are located in one of the most relevant and sensitive regions in the world from the environmental point of view, composing the only ecological corridor that connects several Indigenous Lands and federal and state Conservation Units”.

It is not the first anti-environmental decree of Colonel Marcos Rocha’s government. In January, he legalized gold mining on the Madeira River. “Historical day”, published the governor on Twitter. Colonel Rocha pointed out that his father-in-law was a gold digger and worked out of the law for many years. The activity leaves a trail of mercury, a toxic metal, which contaminates fish and compromises the health of those who use the water.

The dismantling of the reserve areas is yet another project in this sense, according to the Broad Front for the Defense of Protected Areas in Rondônia. If the bill comes into force, it opens the way for the legalization of tens of thousands of kilometers that have been stolen by land grabbers and deforested for livestock.