The scene does not buzz with activity like the human ant-farms that were the hallmark of mining at Serra Pelada, in Pará. At the Yanomami Indigenous Land in Roraima, illegal mining destroys the Amazon forest in a more scattered, but no less vicious manner. Gold mining sites are dispersed over the rivers Uraricoera, Parima, Mucajaí and Couto de Magalhães. In each of them, the soil that has been exposed in extensive clearings tint the previously green landscape with a golden-brown, almost rusty hue. They are like open scars. Muddy water trickles from sediment ponds and runs into the rivers. In the sludge there is a lot of mercury, still widely used in the extraction of the coveted ore. But there is also the blood of the Yanomami people, who yearn for help.

“You’ll see many bad things from the plane; big machines. You’ll be feeling sad, as sad as ever, sad as if a person has come into your home and ruined your land. You’ll see that we are speaking the truth. You can see, so you’ll believe”, warned indigenous leader Davi Kopenawa Yanomami. Recognized worldwide as a leader in the fight for the rights of the Yanomami Indigenous Land (TI), Davi Kopenawa authorized the flight over illegal mining areas on April 30. He knew there would be risks.

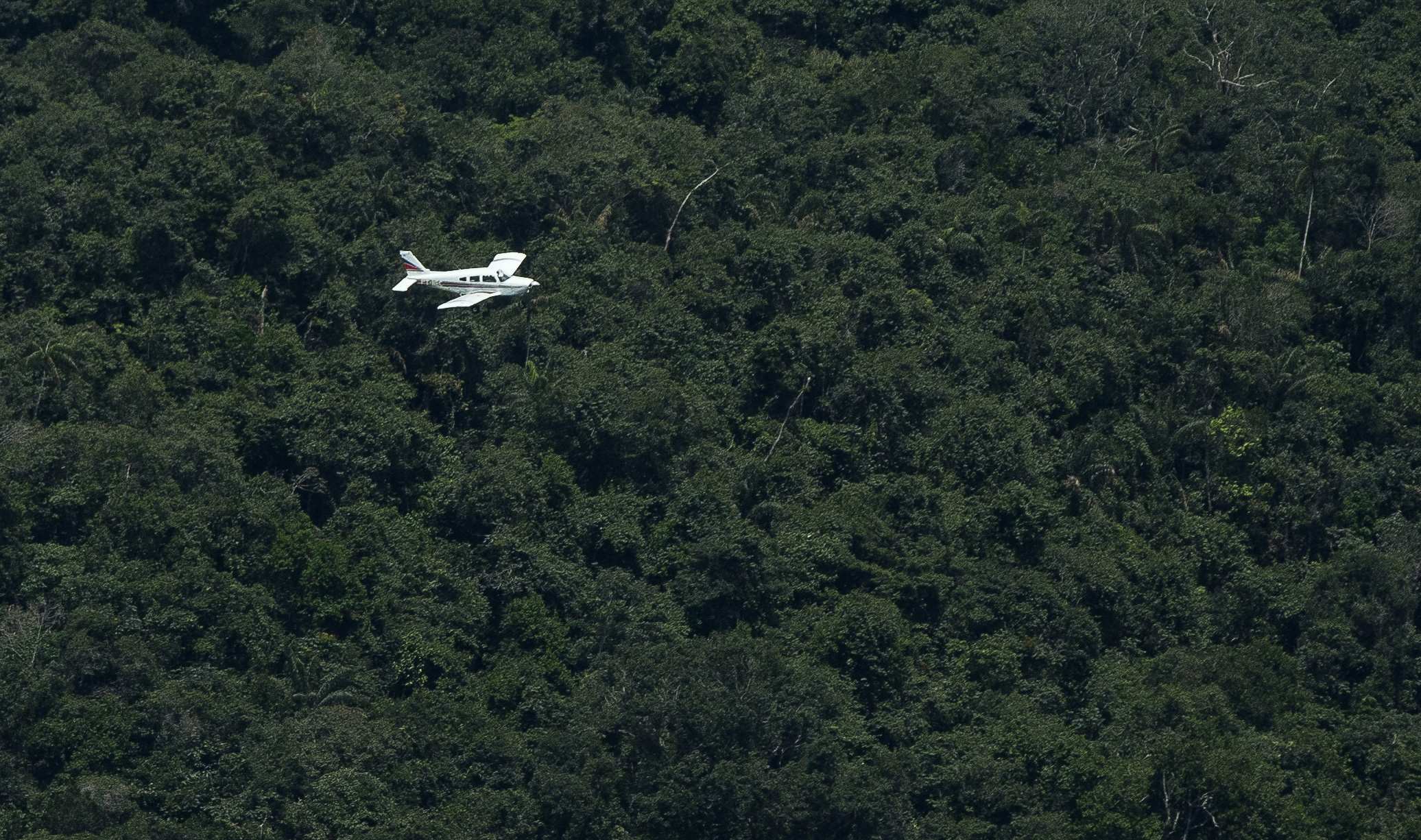

The plane left Boa Vista, the capital city of the state of Roraima, and took one hour to get to the first mining area. The green of the Amazon forest prevailed in the landscape during the first 30 minutes of the flight, already within the limits of the TI Yanomami, when a small plane crossed in front of the aircraft that carried the reporters. Located in the far north of Brazil, the 9.6 million hectare indigenous land lies between the states of Roraima and Amazonas and extends to the border with Venezuela. During the flight, as the number of clearings caused by devastation from illegal mining increased, so did the presence of planes and helicopters flying over the area, as if the earth and the skies belonged to illegal miners. This is the third major gold rush since the seventies.

Amazônia Real joined Repórter Brasil to carry out a comprehensive investigation of the problem of illegal mining in the largest indigenous land in Brazil. It took four months of investigation and the examination of over 5 thousand pages of documents to outline the gold path, to identify the main buyers, to understand the weaknesses in the applicable laws (which exempt buyers from liability), , to bring to light the long lasting interest of politicians in the activity and to reveal the swift approach of illegal mining and international drug trafficking. The investigation had access to two Federal Police inquiries under the Access to Information Law (LAI) and to the indictments brought by the Federal Public Prosecutors’ Office based on anti-illegal mining operations carried out at the TI Yanomami since 2012.

The Yanomami Blood Gold special report – which includes seven articles – shows that right now there is a profusion of stakeholders getting rich from illegal activities in the indigenous land of this country. This is a continuous crime that has been defended by president Jair Bolsonaro’s administration and tolerated by society.

Irregular flights

Aboard a Caravan plane, the Amazônia Real team flew over five areas of the TI Yanomami in April this year, two weeks before the shooting attack against the Palimiu community by miners linked to the criminal faction known as PCC (Primeiro Comando da Capital). Paapiu, Homoxi, Xitei, Parima and Waikás were the areas identified by the Hutukara Yanomami Association (HAY) as being the most critical. Many miners are found in those areas, and there is an overt presence of rafts, machinery and speedboats, in addition to contamination of water by mercury and large-scale logging.

Despite their irregular status, planes and helicopters fly freely, with no apparent concern or fear about the fact that they are breaking into [restricted-?] air space. It looks as if the three army Special Frontier Platoons were not even there to stop them. In a miner’s sky, it is the miner who makes the rules.

“You’ll see many bad things from the plane; machines… You’ll be feeling sad, as sad as ever, sad as if a person has come into your home and ruined your land, warned indigenous leader Davi Kopenawa Yanomami.

In the region of Homoxi, one aircraft kept flying in circles below the reporters’ Caravan, until we went away. The risk of “being shot by a miner”, in the words of our pilot, prevented us from flying lower and shortened the fly-over certain mining areas so as not to draw attention.

In one pilot-to-pilot conversation, the pilot working for the miners asked the pilot flying the reporters who he had aboard and whether his aircraft would land. Our pilot decided not to let him know that there was a photographer and a reporter aboard. According to him, it was safer this way.

In mining areas, planes play an essential role: they transport probes, pumps, chainsaws, washing gutters, hoses, metal detectors and mercury, all of which are necessary for the mining of gold, in addition to supplies to keep miners confined for weeks on end, leaving no doubt about who are the bosses in the area. They are the ones who collect the precious stone, prospect new mines and keep the gold activity in full swing. Cattle farmers have a mantra: “What fattens the cattle is the eye of the owner”. In mining, gold is the cattle.

A trail of destruction

During the two-hour flight, traces of destruction caused by illegal mining could be seen constantly. There are few places where our eyes could rest over stretches of preserved forest, without invaders and the huge holes caused by men and machines mining for gold. The close proximity between mining areas, non-indigenous campgrounds and clandestine airstrips and the huts and swiddens of the Yanomami communities shows how bold the invaders are and how sure they feel about their own impunity.

Invaders look like hungry pigs, according to Davi Kopenawa. “Miners are like pigs raised in the city, they dig a lot of holes looking for gold and diamonds”. Kopenawa witnessed the results and the violence of invasions during the Haximu massacre, in Upper Orinoco, Venezuela, in 1993, when miners armed with guns and knives conducted a series of attacks that killed 16 Yanomami. That was the first case of genocide recognized by the Brazilian Courts. Davi is afraid to see history repeating itself.

Flying at an altitude of 2000 feet (600 meters above the ground), reporters saw invaders working in huge craters, trying to extract gold from pits and gullies. The movement of boats on the rivers bringing supplies to miners is intense. From above, it is easy to identify the operation of a complex land, water and air logistics organization, which enables illegal gold mining at the TI Yanomami to take place at an intense and frantic scale.

The “Cicatrizes na Floresta – Evolução do Garimpo Ilegal na Terra Indígena Yanomami” (“Scars in the Forest – Evolution of Illegal Mining in the Yanomami Indigenous Land”) report released in March 2021 by the Hutukara Yanomami Association (HAY) and the Wanasseduume Ye’kwana Association (Seduume), mentions the existence of about 20,000 illegal miners in the territory. However, the miners themselves report an ever higher figure. According to pilot and historic miner José Altino Machado, there would be more than 26 thousand men involved in what is known as the third gold rush in Roraima. Zé Altino, as he is better known, is chairman of the Union of Miners of the Legal Amazon and was responsible for the first and second invasions of the territory in the seventies and eighties.

Clandestine airstrips

In addition to the planes and helicopters, machinery, rafts and speedboats that Davi Kopenawa had warned about, there are countless clandestine airstrips, of different sizes, tearing through the forest. Some are right beside Yanomami huts. There are also rafts and heavy machinery alongside some communities and indigenous swiddens.

Mining sites are getting increasingly close to indigenous villages, bringing diseases with them. Between 2014 and 2019, malaria cases increased fivefold at TI Yanomami; mercury contamination has also increased.

In the Homoxi region, on the border with Venezuela, miners have built a housing compound a few meters away from an indigenous community. On one side of a bayou contaminated by mercury, one large hut and over two smaller ones are surrounded by the community’s swidden area, where food for the entire village is cultivated. On the other side of the bayou, the invaders have set their own campground. The scene is marked by all the trappings of gold mining: a silted river, huge holes excavated in the dirt and sediments ponds left behind by the flurry of illegal activity.

There are many scars left behind by miners at the TI Yanomami. Once the extraction of gold is depleted, it’s time for them to break camp, collect their makeshift blue tarp tents and head to another mining site. If the mine is “profitable”, miners spend months working it. Otherwise, they leave for another site in what they consider to be a no-man’s land. In any given mining site, the concentration of a metal as rare as gold is only a few grams per ton of mined earth.

The Brazilian Air Force, according to the Ministry of Defense, monitors the airspace 24 hours a day, and if there are suspicious and unidentified aircraft flying over TI Yanomami, there are interception procedures. In a note sent to the reporters, the ministry claims to act “permanently in the fight against cross-border and environmental crime” and that the actions are coordinated by the Military Operation Center 4, which is part of the 4th Integrated Center for Air Defense and Air Traffic Control (Cindacta), located In Manaus.

2,430 hectares destroyed

The proximity between miners and the indigenous population and the risk that this entails were described in the report produced by the Yanomami. On the one hand, there is a worsening of the epidemiological situation, including an increase in the number of cases of malaria. With deforestation, the proliferation of the Anopheles mosquito increases, leading to increased transmission of the disease. Between 2014 and 2019, the cases of malaria have quintupled in the TI Yanomami. Besides, mining activities are also related to high rates of contamination by mercury, which is used to separate the gold (the heavy and toxic metal creates an amalgam that is later incinerated and volatilized, being carried by the wind), causing long-term and irreversible damages to the health of indigenous peoples, in addition to generating economic disruption and leading to violent conflicts.

The size of the destruction caused by the illegal gold mining has reached 2,430 hectares at the TI Yanomami, which is equivalent to 2,430 soccer fields, according to the most recent report released by HAY, in May of this year. In 2020 alone, the deterioration has advanced 500 hectares, as a result of the intensification of the use of heavy and sophisticated material in the extraction of ore. Mining activities are proliferating in the territory, up the rivers, with growing groups of invaders and new routes of access to the interior of the Amazon forest.

The Waikás land, known as Tatuzão do Mutum, remains at the top of the devastation rank. In 2017, the site had a structure that, until then, was unprecedented in the indigenous lands of Roraima, which included houses, a grocery store, access to the internet and hairdressers.

Even though the area has already been the target of Army operations, it is possible to see, from the plane window, that the clandestine activities have not ceased. There are housing structures built along the bed of the Uraricoera river but also deep into the woods. Approximately 35% of the Waikás land has already been degraded.

The area is located a few minutes away from the Palimiu community, where the first shooting attack against the Yanomami people perpetrated by miners linked to the PCC took place, according to the first-hand information reported by Amazônia Real. The feeling, even from above, is one of accelerated destruction and impotence. As Kopenawa told the reporter: “our enemies are many and we are few”.

‘This gold is valuable to city people. People use gold around their necks, on their noses, to look beautiful and to get married. To me, it’s a different culture. But this gold is dirty, this gold is full of the blood of my people, the Yanomami. This is gold that kills nature, kills water life, the water is dead. I do not like to see a woman, a man, wearing gold full of the blood of my people, the Yanomami.’ Davi Kopenawa Yanomami

Yanomami Blood Gold Teams

Amazônia Real: Kátia Brasil (executive editor); Eduardo Nunomura (special editor); Alberto Cesar Araujo (photography editor), Elaíze Farias (content editor); Maria Fernanda Ribeiro, Clara Britto and Alicia Lobato (reporters); Bruno Kelly (flight photographer) and Paulo Dessana (photographer); Lívia Lemos (social media); Maria Cecília Costa (executive assistant); Giovanny Vera (maps); César Nogueira (editing); Nelson Mota (developer); and Ana Cecília Maranhão Godoy (translator).

Repórter Brasil: Ana Magalhães (journalism coordinator); Mariana Della Barba (editor); Mayra Sartorato (social media editor); Piero Locatelli and Guilherme Henrique (reporters); Joyce Cardoso (intern).