With maracas and firm steps, various different indigenous peoples have been constantly protesting in Brasília during the administration of Jair Bolsonaro (PL). The demonstrations show how the last four years were a time of protest – and struggle – for Brazilian indigenous people who, in addition to having to face a pandemic without the promised and needed government support, continue to suffer from invasion of their territories, illegal mining, loggers, and an anti-indigenous administration.

Threats translate into figures: in 2021, there were 118 cases of conflicts related to territorial rights and 305 cases of encroachment, illegal exploitation of resources, and damage to property directly affecting 226 indigenous lands across the country, according to the Missionary Council for Indigenous People (CIMI). Violence against indigenous rights during the Bolsonaro administration was so strong that the Coordination of Indigenous Peoples of Brazil (APIB) exposed the violations to global organizations in the ‘International Complaints Dossier of Brazil’s Indigenous Peoples.’

With the election of Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (PT), the indigenous movement has been reflecting on their next steps to include their rights in the new administration’s reconstruction agenda. But which are the most urgent measures? We heard indigenous leaders and organizations to find that out and understand the challenge of implementing them.

1. Demarcation of indigenous lands

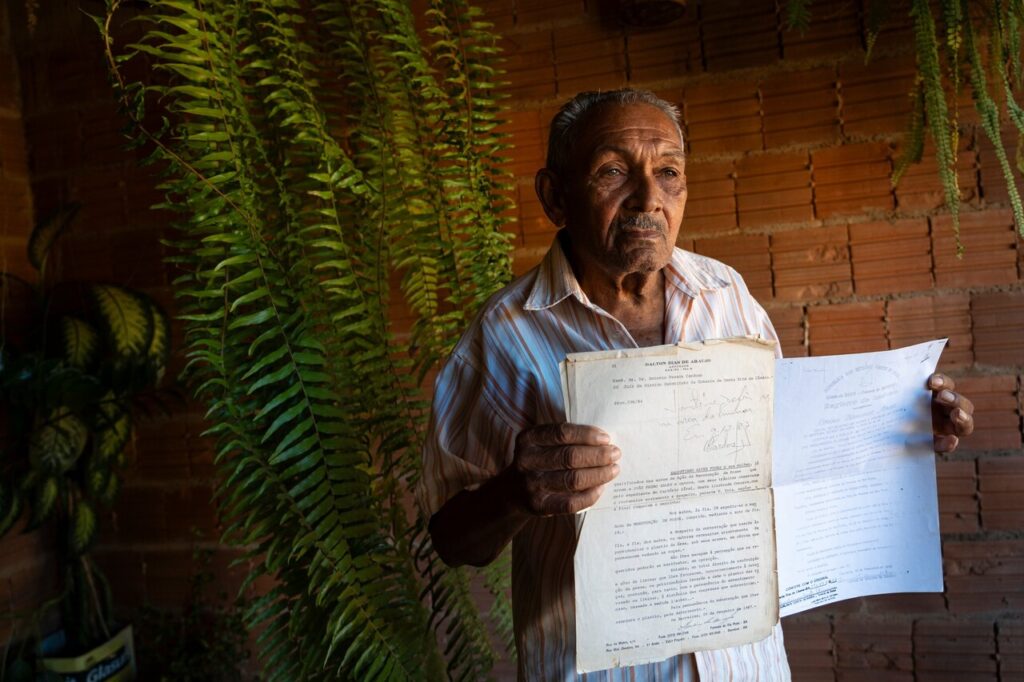

Brazil stopped demarcating indigenous lands – one of Bolsonaro’s promises during his campaign – five years ago. This should be precisely the number 1 priority of the new administration, according to indigenous leaders interviewed by Repórter Brasil. Marivelton Baré, president of the Federation of Indigenous Organizations of Rio Negro (FOIRN), points out that some territories are ready for official approval. “The Lula administration must officially approve indigenous lands that have been waiting for a long time, where all stages of anthropological, environmental and land studies have already been concluded.”

The transitional government’s working group (WG) on indigenous peoples has already delivered the list of 13 indigenous lands whose processes have been completed and which can be officially confirmed immediately. Located in the North, Northeast, Centre-West and South regions, the areas ready to be demarcated include territories belonging to peoples such as the Pataxó, Tremembé, Kaingang, Guarani, Tukano and Komama, among others.

2. FUNAI: more isolated indigenous peoples and no military staff

The dismantling of pro-indigenous policies by the Bolsonaro administration is illustrated by the partial veto to the budget provided for in the Annual Budget Law (LOA) for “regularizing, demarcating and enforcing indigenous lands and protecting isolated indigenous peoples.”

Reversing such budget cuts should be a priority for the new administration, according to Beto Marubo, a leader of the Union of Indigenous Peoples of the Javari Valley (UNIVAJA), a territory that concentrates the largest number of isolated peoples on the planet. He stresses that the budgets of FUNAI (the National Indian Foundation) and SESAI (Special Secretariat for Indigenous Health) must be reviewed, since their dismantling has a direct impact on the villages. “These agencies must be reorganized and have their budgets re-established. They are working with only part of the resources, which causes a series of problems in our territories and especially for isolated ‘relatives’ who live in the region and need government protection,” Marubo said. In Brazil, there are 114 registered indigenous peoples in voluntary isolation, according to data from the Coordination of Indigenous Organizations of the Brazilian Amazon (COIAB).

A weak FUNAI also affects demarcation of indigenous lands, which would be one of its main functions. “We spent four years without actually counting on any government action through FUNAI, which was completely militarized,” says APIB’s executive coordinator Kleber Karipuna. And the problem with the presence of military staff in the context of Bolsonarism is their authoritarianism. We have a recent history of managers acting specifically to persecute indigenous and non-indigenous servants just for supporting the indigenous movement or opposing a certain decision that would go against the very indigenous policies,” he explains.

Currently, Funai is presided over by Federal Police Commanding Officer Marcelo Augusto Xavier, with support from Congress members representing big landowners. A champion of legalizing mining on indigenous lands, he was once an advisor to special secretary for Land Affairs Nabhan Garcia, who also serves as the licensed president of the Ruralist Democratic Association, a landowner’s lobby group.

“FUNAI needs to be realigned; we are at a very favourable moment for indigenous peoples to take a leading role, with appointment of indigenous representatives who will resume land demarcation, create working groups and once again dynamize the discussion on the country’s territorial management policy for indigenous lands,” Karipuna adds.

For indigenous leader Maial Kaiapó, all the military staff in positions at indigenous health agencies and FUNAI must go. “It’s not just about reviewing budgets; we have to remove the invaders from indigenist bodies, the government must take care of it, we urgently need these people to get out of the places we struggled so much to establish.” FOIRN’s Baré also recalls that in addition to strengthening FUNAI and SESAI, the creation of the Ministry of Indigenous Peoples is crucial.

3. Repealing regulations and evicting encroachers

Bolsonaro enacted numerous regulations that violate indigenous rights, such as Bill 490/2007, which changes the Statute of Indigenous Peoples in the land demarcation process; and Bill 191/2020, which opens indigenous territories to large enterprises and exploitation of water resources without prior, free and informed consultation.

In this regard, Maial Kaiapó points out the urgency of repealing these regulations and the need to evict encroachers: “There are many requests for the removal of people who are invading our land to destroy the forest, so I believe that the mission now is to remove these people who are destroying our home. Another priority is the immediate repeal of these bills that are pending in Congress.”

For Beto Marubo, these measures are extremely harmful to indigenous peoples and encroachers must be removed in joint actions by several agencies. “To face the high level of crime and drug trafficking that has been happening along with the invasions of indigenous lands, the Federal Police, IBAMA and the Environmental Police must work together. Putting in a permanent force to inspect and monitor indigenous lands is also crucial.”

4. Strengthening environmental policies and funds

In November, the eyes of the world turned to COP-27, held in Sharm El Sheikh, Egypt. This edition was attended by President-elect Lula and was marked by Brazil’s return to the main debates on climate change – a scenario that brings back indigenous movements’ hopes in the face of so many environmental setbacks in the last four years, along with frozen funds aimed mainly at protecting the Amazon.

Toya Manchineri, head of the Coordination of Indigenous Organizations in the Brazilian Amazon (Coiab), stresses the importance of resuming the Amazon Fund and highlights the need to strengthen environmental policies. “We have lived through dark times, but it’s time for us to return. I believe that the new President will bring back the Amazon Fund, which is essential to support projects in indigenous territories. But of course, everything has to undergo consultation; nothing should be done in a top-down fashion but rather with dialogue,” he says. “We can’t forget the presence of traditional peoples in the main official debates on climate change.”

Marubo says that human resources in environmental protection agencies such as IBAMA and ICMBio will have to be replaced. “You’ll have to hire people, and that means increasing the budget; there will be costs, but it’s necessary. It’s very important that these spaces are included in the administration’s planning,” he concluded.

5. Specific and distinguished education

A challenge facing the Lula administration is seriously implementing specific education for indigenous peoples, provided for in the 1988 Constitution. “Specific indigenous education focused on the reality of our peoples must be a priority in the Lula administration, and for that to happen, the Ministry of Education must listen to our peoples.”

Marubo reports that the lack of quality education has forced many students to leave their territories. “Education in indigenous villages has been horrible, at least in my area, but I believe it’s also a standard in other areas. It’s one of the reasons for more young people to leave their lands,” he says. “And this has created serious social problems such as prostitution, recruitment by drug trafficking, violence, because when they leave for the city, they are forgotten, they are left without any protection.”

In the various areas addressed in this report, all the indigenous leaders heard said they hoped that political parties, deputies and allies could dialogue and acknowledge indigenous representation, always consulting native peoples and respecting their decision-making processes.