In November 2022, Repórter Brasil and Greenpeace revealed that JBS, one of the largest meatpackers on the planet, purchased 8,785 head of cattle reared in deforested areas of the Brazilian state of Rondônia, in the Amazon.

Along the same lines, an investigation conducted by Revista Piauí, news agency Fiquem Sabendo and Center for Climate Crime Analysis (CCCA) in July 2022 indicated that, between 2018 and 2021, at least 91,200 cattle were sourced from illegally occupied public lands in the state of Pará. In 2020, Agência Pública revealed laundering operations involving cattle reared on indigenous land in the state of Mato Grosso.

What do these investigations have in common? The fact that all of them were conducted by journalists and researchers and used cattle transport permits (GTA — Guia de Trânsito Animal) as their main sources of data. GTAs are state documents used for cattle health surveillance purposes.

GTAs contain essential pieces of information that enable greater cattle traceability, like origin, destination, purpose, species, vaccination status and more.

Because of this, experts from multiple areas present arguments in favor of the disclosure of GTA data, including protecting public health, environmental monitoring, regulating livestock farming and assessing the facilities in which cattle is raised.

Despite the obvious and repeatedly demonstrated importance of this data for social control, access to it is virtually impossible through official channels, since state and federal governments claim that these documents are confidential. The justifications given for confidentiality vary and include the allegation that this information could affect the competitiveness of companies (trade secrecy) or that this is ‘private data’ (which could in theory be used to maintain secrecy for up to 100 years, under article 31 of Brazil’s Law on Access to Information — LAI).

Global Witness, in partnership with the DataFixers.org project, hosted at Columbia University and specialized in accessing data on environmental crime, filed a series of requests for information in recent months and spoke with specialists to demonstrate how difficult it is to access this data. For the purposes of our research, we submitted requests to the states of Mato Grosso, Pará and Acre between the months of November 2022 and January 2023. These are three states inserted in the Legal Amazon, a territory where cattle raising is the biggest vector of deforestation, according to a recent study by Imazon.

Our requests required access to the full data of GTAs, including name, address, number of cattle, size of the herd and more. The applicant informed that he was a researcher formally linked to a university research center and attached proof of this status to all the requests.

Every request presented a long explanation of why access must be granted in cases of wide public interest for research purposes, pursuant to article 57 of the decree that regulated the country’s Law on Access to Information, which exempts these cases from the need to obtain the data holder’s consent.

Law violations begin long before the GTAs

One of the conclusions of this survey was that, even before the specific problems with GTAs, state agencies fail to comply with the Law on Access to Information.

The state of Acre did not even reply to our requests for information. Requests were filed on December 6, 2022, and new requests demanding a response were resubmitted on January 10, 2023. All of them were ignored. A complaint was then made to the state’s comptroller office, which claims to have notified the competent bodies and demanded a response. Ignoring requests grounded on the Law on Access to Information should entail punishments for the rejecting body — but so far we have received no clarification about that.

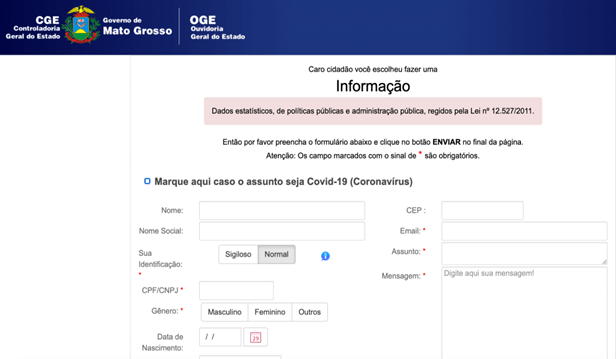

In Mato Grosso, LAI violations start with the design of the website where requests have to be filed. The state government “conceals” its channel for filing requests and, unlike other states, does not even call the service by its standard name (Serviço de Informação ao Cidadão, or e-SIC). When responses arrive via email, citizens are redirected to a link that is always down to access the response.

The link contained in the CGU message seems to contain an error, as there is a fragment (:80) in the middle of the address, which, if removed, makes the online linking work.

After the initial challenge in Mato Grosso, we finally got a response, but the data was shared only in summary form, via two links (here and here) without the names of the owners, which were denied based on Brazil’s General Data Protection Law (LGPD).

We tried to question this refusal, but another serious problem appeared in the structure of the form itself: there is only a field for registering requests for information, but there is no way to file an appeal if the applicant disagrees with the response. The only way to do it is by registering a new request and starting the whole process all over again. The Law on Access to Information expressly states that allowing citizens to file an appeal is mandatory for all public bodies.

The body defended itself by claiming that any appeals are “internally” linked to the request, even when a new request is filed. However, in our case, the appeal was ignored — we opened a new request on December 13th and never got a response either, although the law says that the maximum period for fulfilling an appeal is five days.

Since the entry into force of the Law on Access to Information, at least 17 requests for information about GTAs have been made to the agricultural defense agency of the state of Mato Grosso (Indea), according to data provided by the agency to Global Witness, in partnership with the DataFixers.org project.

Of these, seven were denied on the grounds that the requested information was private or protected by some type of secrecy, three claimed that the information did not exist and the rest referred the applicant to government websites that show generic information on the matter, without any detailing on the requested data (as in the case of the response we received). For those that were granted (only three), the requests were more generic: one of them, from 2016, asked for the total number of GTAs issued in 2015. Another two, made in 2020, asked for specific information on how to issue a GTA and rules and regulations that deal with the transparency of these documents.

Although Mato Grosso shared some information on the number of issued GTAs, in Pará the lack of transparency is so severe that we did not even received simple statistics on requests for information, under the allegation that this data could also violate data privacy laws. Talking to specialists we were able to identify at least one case where the GTAs were granted to a citizen in a request for information, after several appeals in 2022, but other requests—including ours—were denied at all levels, always based on the LGPD.

Pará is failing to follow a recommendation made in 2015 by the Federal Prosecution Office (MPF) to the agricultural defense agency of Pará (Adepará) to fully disclose GTA information, including number, date of issuance, transported volume, origin (CPF, CNPJ, name, establishment, municipality), destination (CPF/CNPJ, name, establishment, municipality), age, purpose, shipping unit and observations. The MPF noted that “wide access to data from cattle transport permits is essential to uphold the principle of access to environmental information about the livestock chain, as it should allow citizens and civil society to monitor the environmental implications of this activity more accurately.”

* Luiz Fernando Toledo is the creator of datafixers.org, which is funded by the Brown Institute for Media Innovation (Columbia University). Research for this article was done in collaboration with Global Witness

The articles published are the responsibility of their authors and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Repórter Brasil.