In the municipality of Itaituba, Pará, a port used by agribusiness giant Cargill to load and unload grain on the right bank of the Tapajós – one of the most important rivers in the Brazilian Amazon – has operated under a provisional license for a year and a half.

The company was granted an automatic extension of its operating license, which expired in April 2022, without approval by technicians from the State Department for the Environment and Sustainability (Secretaria de Estado de Meio Ambiente e Sustentabilidade, SEMAS) – a mandatory stage in the licensing process. The problem is that some of the companies’ duties have not been fulfilled – such as conducting a study on the impacts caused on the Munduruku indigenous people, who own land in the port’s catchment area – in addition to complaints from residents about the adverse consequences of the enterprise.

“The population has grown, and now they face hunger, poverty and vulnerability,” says Jesielita Roma Gouveia, head of the Social Assistance Reference Centre (Centro de Referência de Assistência Social, CRAS), which implements public policies to assist socially vulnerable people. Repórter Brasil went to Itaituba and heard reports of sexual exploitation, pedestrians hit by motor vehicles and widespread insecurity, which residents blame on the enterprise. While violence has grown, fish decreased in the river, according to local residents.

“Environmental agencies have been slow to complete license renewal analyses, which is largely due to lack of structure, staff and institutional resources. This has major impacts, and it makes it difficult to inspect whether the requirements imposed on the enterprise are solving them properly,” says Maurício Guetta, a lawyer at Socio-Environmental Institute (Instituto Socioambiental, ISA), an organization advocating environmental rights.

Automatic extension of the license is supported by a resolution from Brazil’s National Environmental Council (Conselho Nacional do Meio Ambiente, CONAMA), which allows this provisional measure “until the competent environmental agency makes a final decision.” But according to information obtained from SEMAS through the Access to Information Law, there is “no time limit for the conclusion of the technical report on the license renewal process.”

“In practice, this is automatic license renewal,” warns Pedro Martins, a lawyer working with the organization Terra de Direitos, which launched a report early this year on the socio-environmental impacts of Cargill’s port. The document warns of “lack of essential information and poor technical quality” of the company’s environmental impact studies.

Last year, the Federal Supreme Court ruled that granting automatic licenses without analysis by environmental technicians was unconstitutional. “The authorities are granting a benefit so that the company can keep operating. It’s as if renewing the license wasn’t necessary,” Martins adds.

Contacted by Repórter Brasil, Cargill stated that “automatic extension complied with the legislation” and that “all requirements [of the operating license] are fully met.”

SEMAS denied any irregularity and said that “the company filed the request for renewal within the advance period to guarantee automatic extension of the license.” The Department also informed that “the technical note evaluating the status of the requirements for the license is currently being prepared and will be available on the Transparency Portal when completed.” The full statements by Cargill and the Department can be read here.

Itaituba connects Brazil’s large agribusiness sector to Europe

Cargill is not the only company to operate a river port in Itaituba. Other soybean giants such as Bunge and Amaggi, which together founded Unitapajós, are also part of the port complex, which includes logistics companies. Their enterprises operate in Miritituba, a district of Itaituba that used to be a small village and has turned into a “commercial, industrial and port” area.

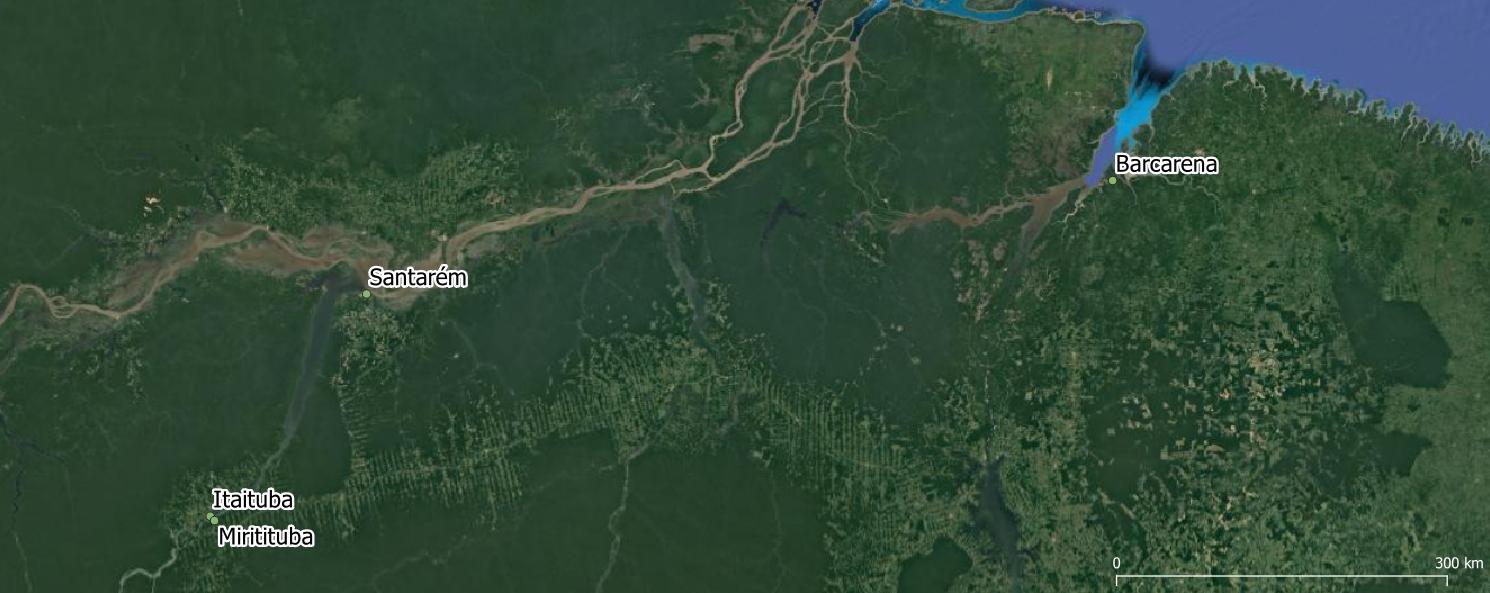

Itaituba’s strategic location was decisive for the establishment of the ports. That point on the map sees the convergence of BR-163 – also known as ‘the soybean road,’ which crosses Mato Grosso, Brazil’s largest soybean producing state – from north to south; the Trans-Amazonia highway, another important route for agricultural production from Brazil’s North region; and the Tapajós-Amazonas waterway, which starts there and runs northwards through these two water bodies to reach ports capable of receiving ships crossing the Atlantic Ocean to Europe or other international destinations.

But Cargill has a strategic advantage over its competitors: it has its own port in Santarém, 360 kilometres from Itaituba – a much shorter route than that used by other companies whose barges departing from Miritituba have to travel a longer way to Barcarena , also in Pará – more than 1,000 kilometres away. Cargill is Brazil’s largest soybean and corn exporter and the largest agribusiness company in the world, according to a survey by Globo Rural magazine.

Residents recognize that the ports boosted Miritituba’s economy and were followed by new restaurants, hotels and laundries. Public services such as CRAS and secondary education have also arrived in recent years, following pressure from the community. “But development always has a negative side,” points out Gouveia from CRAS. Today, Itaituba is the 15th most violent city in the country, according to the Brazilian Public Security Yearbook.

“What kind of development is this where you live in a city with open sewage, with no basic sanitation and where you have to buy water to drink?,” says Raione Lima Campos, a lawyer at the Pastoral Land Commission (Comissão Pastoral da Terra, CPT) in Itaituba. “Historically, the state has not invested in public policies, and when the ports came, the existing issues worsened,” she adds.

Sexual violence threatens childhood

Among the several impacts of the installation of ports in Miritituba, one is especially difficult to document – sexual exploitation and violence against women, including children and adolescents, which increased when the port was built and cargo trucks started circulating. Cargill’s 2013 environmental impact study predicted “increase in the male population” and called this change as a “adverse effect” of “medium” magnitude. An estimated 1,500 trucks per day arrive at the Miritituba district at the height of the soybean harvest season.

“Sexual violence in our area has always been strong, but we can’t pretend that it has not increased,” says Yasmin Correa, a lawyer at the Specialized Reference Centre for Social Assistance (Centro de Referência Especializado em Assistência Social, CREAS) in Itaituba. While CRAS works to prevent violence, it is at CREAS that victims seek care.

The situation is especially serious in Campo Verde, 30 kilometres from Miritituba. In the project submitted in 2013, Cargill planned to build a parking lot for 150 trucks within the port area, but it changed the proposal in the following year: only 15 parking spaces would be reserved in its internal area for trucks to unload, and a yard for 400 trucks would be created in Campo Verde. “Lots of girls stay in the middle of those trucks, but there are no complaints. It’s a difficult crime to prove,” says Maria José de Barros, head of the Itaituba Child and Adolescent Protection Council.

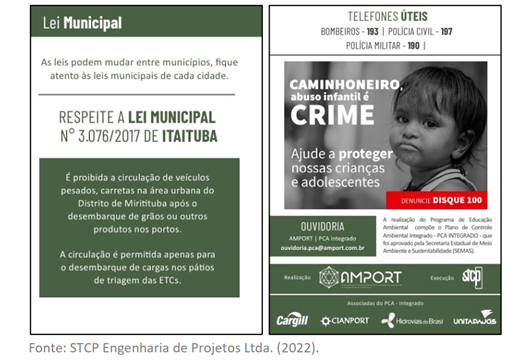

In 2016, Itaituba banned the circulation of trucks in the Miritituba district to prevent accidents with pedestrians in the urban area like the one that killed Edizangela Vieira’s son in 2019. “He came home for lunch, left the plate on the table and went to buy a soda. Then he was run over. I’ve had to go to the side of the road myself many times, to avoid being massacred by a truck,” she says.

As a result, Campo Verde began to concentrate almost all support services for truck drivers such as petrol stations and hotels. Along with that infrastructure, bars and brothels also mushroomed. “There must be four or five nightclubs [in Campo Verde], which appeared after the port business,” says a resident who asked not to be named.

A social worker claims to have witnessed a teenager being exploited in one of these establishments after receiving a complaint from the Child and Adolescent Protection Council. “Apparently it was a bar, but there was a very narrow alley next to the entrance that led to rooms. It was actually a brothel,” she described. There, she says she found a teenage girl working as an ‘escort’ for a truck driver – a service for which the brothel owner had charged R$ 2,000. According to the social worker, in addition to being a victim of sexual exploitation, the girl was not even paid for it. “The owner of the place kept the money,” she added.

Sexual exploitation is a crime provided for in Brazil’s Criminal Code and the Child and Adolescent Statute. Taking advantage of the sexual activities of children or adolescents is considered ‘exploitation.’ Sexual intercourse with anyone under 14 is considered rape. “Children do not prostitute themselves; they are sexually exploited and they have no idea of the problem and its serious consequences for their future lives. They live in poverty, so they think it’s cool to get some money,” adds Barros, from Itaituba’s Children and Adolescent Protection Council.

In a statement, Cargill criticizes “the attempt to link the company’s presence in Miritituba to such serious issues as abuse and exploitation of children and adolescents.” The company informs that it brought the “Na Mão Certa” programme to the area, developed by Childhood Brasil to prevent sexual exploitation of children and adolescents on highways, which includes “training, engagement campaigns, internal communications, among other activities” aimed both its own staff and service providers.

Promoting actions to reduce the impacts of “problems resulting from the increase in migration” is one of the requirements conditioning the license granted to Cargill in 2014, when it began building the port. The requirement remains in force and is handled by Association of Port Terminals and Cargo Transshipment Stations of the Amazon Basin (Associação dos Terminais Portuários e Estações de Transbordo de Cargas da Bacia Amazônica, AMPORT), which represents the companies operating ports in the region.

In a note, the association explained that it does so through “awareness-raising actions such as training, engagement campaigns, internal communications, among other activities.” “Member-companies are always making every effort to work in a preventive and corrective manner to combat sexual exploitation of children and adolescents,” they add. Read the full statements.

Damage control is not enough, says the community

Documents obtained by Repórter Brasil under the Access to Information Law show that, from April 2021 to March 2022, four lectures on sexual violence were held in the truck screening yard shared by Cargill and Unitapajós in Campo Verde.

But Itaituba social workers and civil society groups warn that the actions fall short.

“Lectures won’t do it. That’s a very weak measure considering the impacts,” says sociologist Wwyncla Paz de Aguiar, who works with the Tibira Group, an organization advocating diversity in the Tapajós area. “It’s a serious collective issue, which is why we must do more than holding individual truck drivers accountable,” he adds.

Antonieta Lima, from the coordination of public policies for women in Itaituba, who has attended these awareness-raising activities, agrees. “We carry the message and its acceptance is good, but the culture of violence won’t change overnight,” she points out.

There is also criticism about the financial support provided by the Port Terminals Association – on behalf of the companies that operate ports in Itaituba – to the Miritituba CRAS opened in 2015, also as part of the agenda to mitigate the impacts of the ports. There is where the City promotes so-called social strengthening activities, a public policy designed to prevent violence and provide protection for socially vulnerable people. More than 60 children and youth aged 6-17 participate in capoeira, music and football workshops. Once a week, 35 elderly people attend a collective breakfast.

The Association’s monthly donation is R$ 5,500, which has recently been used to purchase food items and teaching materials: milk, eggs, sugar, notebooks, pens, pencils and modelling clay. But Gouveia, head of the unit, admits that these funds “are not enough.”

“It’s R$ 5,500 from four multinationals. Speaking specifically about Cargill, it provides almost no help to the district,” complains an activist with Miritituba’s social movements. Cargill earned was R$ 125.8 billion in Brazil in 2022 – a 22% increase over the previous year.

Social movements also complain that they are unable to obtain information about taxes or other contributions paid to the City. Therefore, they do not have parameters to demand more robust action against violence.

“The City’s revenues from the ports are very obscure. We have no information on how much these ports pass on to Itaituba to be invested in public services,” says Raione Lima Campos from CPT.

Even the Management Council for Inspection of Investments and Enterprises in the Miritituba District– the agency responsible for monitoring the operations of the ports – have trouble to actually know the figures, according to its president. “It’s zero transparency,” says Naldo Luna, president of the agency created in 2019 to monitor the actions of port companies.

Repórter Brasil contacted the City to find out the amount and destination of the taxes but had not received a reply when this article was finished.

Munduruku indigenous people were not heard

In 2017, the State Department for Environment and Sustainability decided that Cargill would have to conduct an Indigenous Component Study on the Munduruku territories of Praia do Mangue and Praia do Índio – two indigenous areas located within Itaituba, a few kilometres away from the urban area. Together, the two territories total 60 hectares, with almost 300 people.

According to a federal rule, conducting the study is mandatory to project the specific impacts on that population.

The document should have been delivered within four months from when the operating license was granted in April. However, according to Cargill itself, the preliminary work plan for that study was not filed with FUNAI (National Foundation of Indigenous Peoples) until 5 years later, in 2021. Since then, the Port Terminals Association, which is responsible for the plan, has been discussing improvements to the project with the federal agency. “Several meetings were held, and communications were exchanged between the parties, but FUNAI has not issued a definitive opinion on the matter,” the company points out.

Meanwhile, the Munduruku interviewed by Repórter Brasil complain about the increase in violence. Many families prohibited their children from playing alone in the Tapajós. “Things got a lot worse. After the companies arrived, there have been many robberies, deaths, drugs and prostitution,” says Karo Munduruku, one of the indigenous residents of Praia do Mangue.

According to the fishers, they cannot approach the complex. “The fish is completely full of soybean pomace. That’s very bad,” says indigenous chief Brazilino Painhum Munduruku.

Over time, the traditional indigenous diet was replaced by processed food. “We didn’t use to have so much hypertension and diabetes. Now we treat many intestinal illnesses caused by consumption of soft drinks, snacks and canned foods,” says Edilene Munduruku, a health agent from the Praia do Índio village.

Idle capacity waiting for Ferrogrão

In Miritituba, Cargill has a shipping capacity of 24,000 tonnes/day, the equivalent of eight barges. It would be able to move up to 4 million tonnes per year – but documents obtained by Repórter Brasil under the Access to Information Law show that there is idle capacity.

Between April 2021 and March 2022, around 2.5 million tonnes of cargo were received and shipped.

Sources interviewed by Repórter Brasil fear that the adverse impacts will intensify if a project to build a railway parallel to BR-163 – known as Ferrogrão – gets off the ground. This is because the 900-km-plus enterprise is expected to increase the amount of grains transported through Miritituba. The estimate is that up to 52 million tonnes of soybeans, corn and other agricultural products will be moved per year.

Edited by Naira Hofmeister