One of the main people investigated by the Federal Police for drug trafficking and illegal mining in the Amazon, businessman Heverton Soares de Oliveira, known as “Grota”, is said to have entered the gold market in Pará through a scam.

Grota promised 25 kg of ore, the equivalent of R$8 million today, to buy an illegal gold mine in the Tapajós Environmental Protected Area (APA), according to statements collected by the police in the Narcos Gold operation and accessed by Repórter Brasil.

The episode, which took place in 2018, is the first act of the journey that has made Grota a star in the Amazon gold market. The reports collected by the police indicate that he took control of the illegal gold mine at the time, even though he didn’t honor the payment. The scam, however, is the least of the problems, according to the Federal Police’s investigations.

The businessman concentrated his activities in and around the Tapajós protected area: there are 43 illegal gold mining cases related to him, along with those of his brother and partner, according to the police investigation. However, the extraction has taken place without authorization from the competent federal environmental agency.

In order to remove gold from within the protected area, Grota would need the approval of the Chico Mendes Institute for Conservation and Biodiversity (ICMBio), linked to the Ministry of the Environment and responsible for managing the conservation unit. But this never happened, according to what the agency told Repórter Brasil.

Although Grota is facing charges of homicide, association with drug trafficking, involvement with narco-gangs and suspicion of leading a militia group, he has not been indicted or denounced by the federal police and the Pará State Public Prosecutor’s Office (MPPA) for suspicions related to illegal mining.

Illegal ghost mines: far from the eyes, close to the satellites

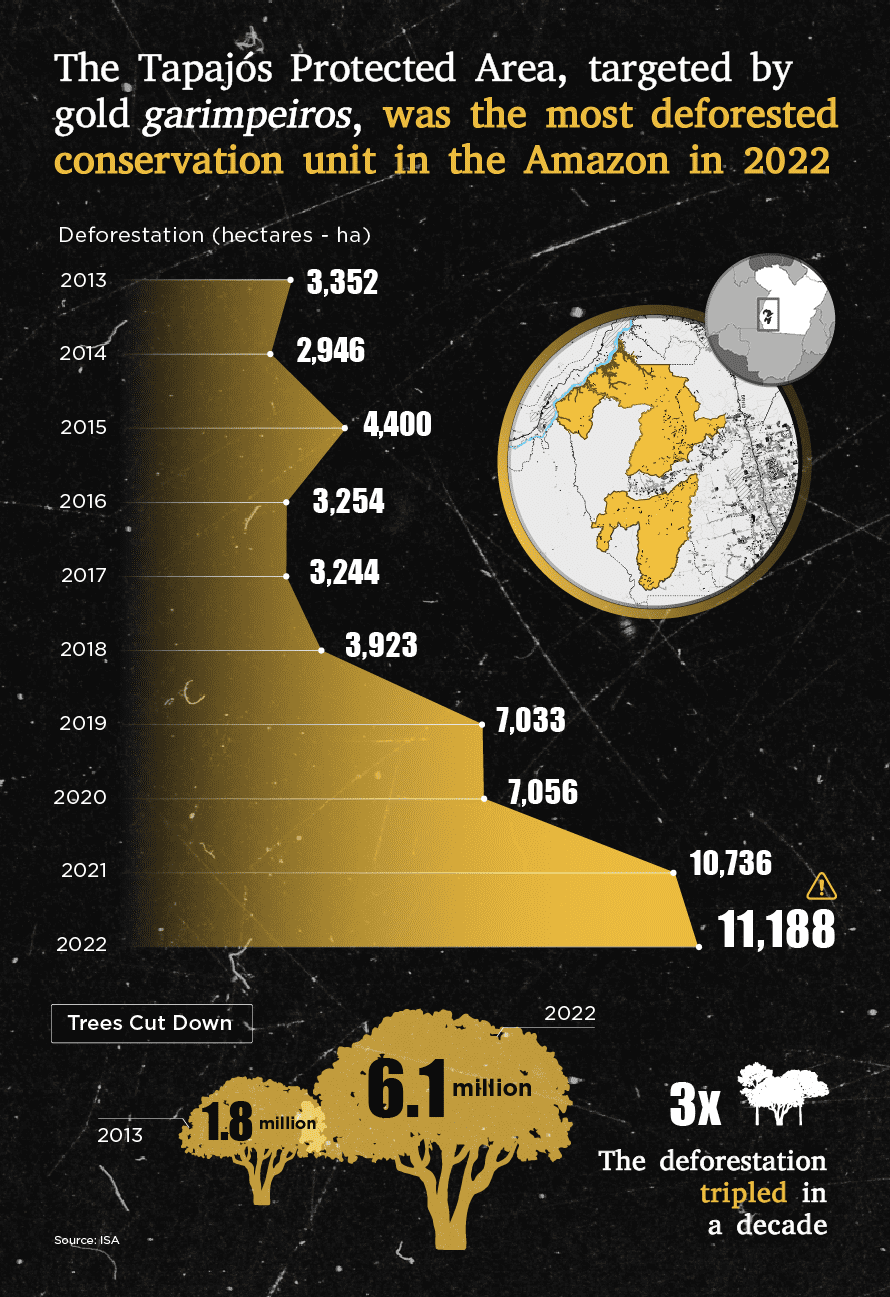

Located in Itaituba, in the state of Pará, the Tapajós protected area is crossed by the Transgarimpeira highway and is a frequent target for illegal miners. In the last five years, deforestation in the area has tripled, reaching 113 km² devastated by 2022, according to data from the Socio-Environmental Institute (ISA). The area is equivalent to 33 Central Parks in New York.

The destruction is similar to the clearing of 6.1 million trees, which places the Tapajós protected area as the most devastated conservation unit last year, among all the protected forests in the Amazon.

A study by the Federal University of Minas Gerais showed that the Tapajós river basin is home to the three cities responsible for 85% of the gold extracted illegally in the country in 2019 and 2020: Itaituba, Jacareacanga, and Novo Progresso.

“These municipalities have been affected by mining for decades, but this has been amplified during the Bolsonaro administration. In the last five years, the region has become an epicenter of demands from groups that want to free mining on indigenous lands and conservation units,” says anthropologist Luisa Molina, from ISA.

Grota also surfed this wave of mining during the administration of former president Jair Bolsonaro (PL). Of the 43 mining processes regarding him and his group, according to the police investigation, 31 received authorization from the National Mining Agency (ANM) during the Bolsonaro administration. In addition, 22 affect the Tapajós protected area, according to the federal agency’s database.

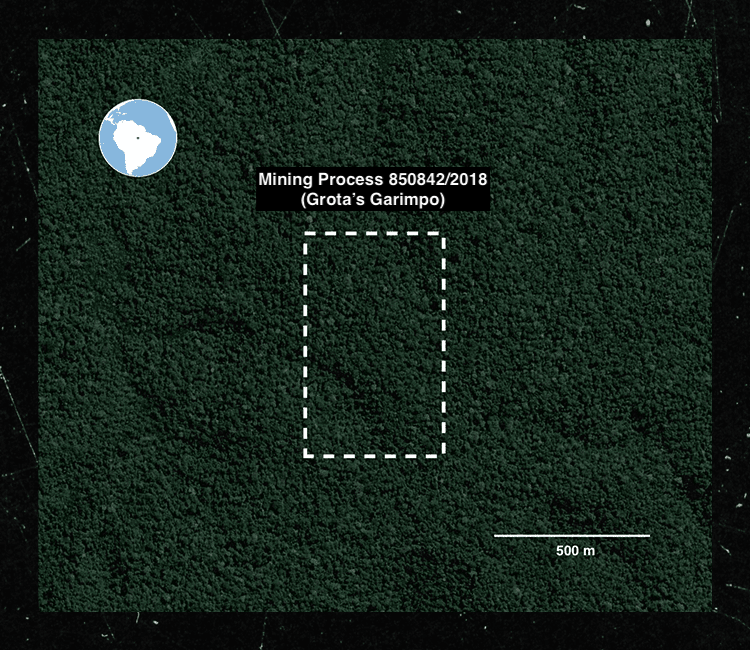

In three of these mining processes (all in the name of Grota’s brother, Diego Oliveira), there are signs of what experts classify as “ghost mines”.

“These are places where there is a mining application registered with the ANM, but without any sign of exploitation. The mining license only exists to validate the gold extracted from potentially illegal areas. This is a form of money laundering,” says Cesar Diniz, coordinator of MapBiomas’ Coastal Zone and Mining team.

In practice, these are areas that have been registered with the regulatory agency and even have had taxes collected for gold extraction, but without any sign of mining activity captured by satellites.

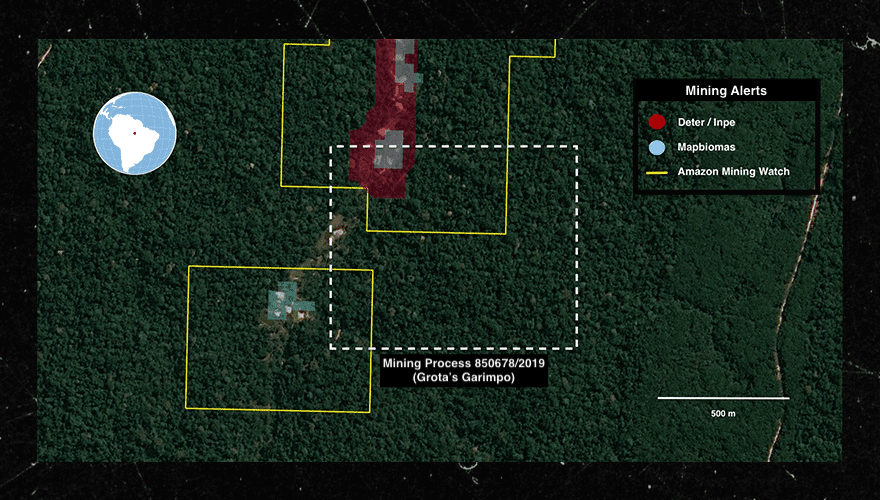

In order to determine whether or not there was mining activity in the Grota mines, the report extracted data from the Amazon Mining Watch by Earth Genome and Pulitzer Center, and MapBiomas platforms, as well as information from the program Deter, from the National Institute for Space Research’s (INPE) deforestation verification system.

“MapBiomas uses artificial intelligence to detect deforestation by mining, and for this it also considers information from other deforestation analysis systems, such as Deter and Amazon Mining Watch. There is a margin of error in each platform, but when all three find mining at the same point, there is hardly any mistake,” explains Diniz.

Between January and February 2020, these three gold mines in the name of Grota’s brother showed no sign of mining activity, according to the three systems consulted. However, Diego Oliveira informed the ANM of the production of 6 kg of gold at the site, equivalent to R$1.8 million at the current market rate.

Another potential irregularity was found in two other mines (these under Grota’s name): there are signs of mining captured by satellite image mining detection systems, but without proper registration with the ANM – every gram of ore extracted from the ground must be reported to the agency.

Once proven, this lack of communication could mean that no tax was paid on what was extracted at the site. In other words, the environmental damage occurred without any financial compensation to the Federal Government.

Although they are in Grota’s name, it is not possible to confirm who mined at the site, since the extraction and taxes were not registered with the ANM. The mining tax for gold is 1.5% of the operation. Considering the price of gold at R$300 per gram, the prospector is obliged to pay almost R$5 for each gram taken from the earth.

According to the 2020 Annual Mining Report sent by Grota to the regulatory agency, and attached by the Federal Police to the inquiry investigating the businessman’s operations, he would have earned R$5 million from the sale of 17.6 kg of gold that year, considering all the mines associated with his group.

However, the tax collected, another database from the ANM itself, shows that total production was only 7.8 kg. Grota’s lawyers were asked by Repórter Brasil if the production of the mines was artificially inflated in the 2020 report. However, there has been no response yet.

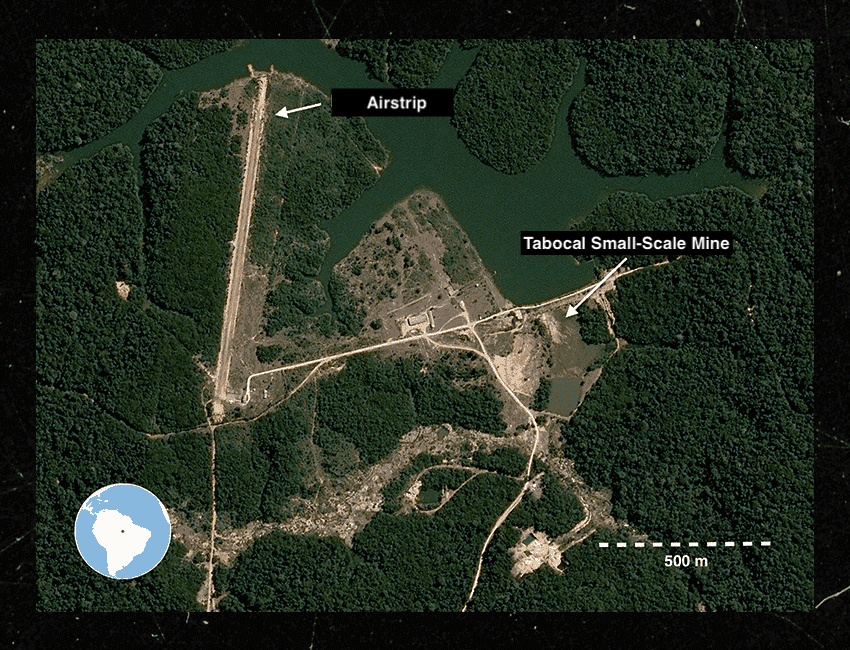

Grota and his group were the targets of Narcos Gold, which was launched in 2021 to investigate the links between illegal gold mining in the Amazon and drug trafficking. Based on this investigation, the Pará State Public Prosecutor’s Office filed a complaint in March 2022 pointing out that Grota used his brother Diego as an alias to launder money through gold, and also to purchase farms and airstrips under his name.

The law firm that represents Grota and his brother responded in a statement that “the technical defense is convinced that the indisputable innocence of the accused will be proven in the end”. Read the full response here.

The note classifies the Narcos Gold investigation as “a story with crazy aspects” and argues that the investigations, even though they have been going on for almost three years, “have not managed to add a single piece of evidence to the charges”.

When asked specifically about the gold mines mentioned in the police investigation, however, the defense did not comment on the matter.

Reporter Brasil questioned the ANM about the reason for authorizing mining activity within the Tapajós protected area. However, no reply was received at the time of writing.

ICMBio said it carried out eight inspection operations to “combat illegal mining and deforestation” within the conservation unit in the first eight months of 2023. The result of these efforts was the “application of 91 infraction notices, as well as the burning of 144 pieces of equipment and the seizure of 4,000 hectares”.

The institute also pointed out that the number of operations in 2023 already exceeds the volume of actions carried out in the last two years.

The role of municipalities

Although the Tapajós is a protected area, it would be possible to mine gold there if ICMBio granted permission, which has never happened. However, the prospectors find loopholes that give the exploration a veneer of legality, according to the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office.

In Pará, resolution 162/2021 of the State Environment Council (Coema) establishes that mining operations have a “local impact”. Thus, municipalities are authorized by the state rule to license mining operations. However, this rule is contested by the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office. The prosecutor’s office argues that the issue is a state matter, not a municipal one.

In February of this year, 21 federal prosecutors signed a recommendation for the government of Pará to annul the rule, arguing that there is no control over the authorizations granted and that they cause a high environmental impact, citing the Tapajós basin itself as an example.

When contacted by Repórter Brasil to comment on the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office’s recommendation to change the environmental licensing of mining operations in the state, the government of Pará did not reply by the time this report was published.

In the midst of the controversy, municipalities are using the resolution to encourage illegal mining in federal conservation units. In the case of the 22 mines allocated to Grota, which overlap with the Tapajós protected area, it was the Itaituba Environment and Mining department that issued the environmental licenses.

The secretary of the department, Bruno Rolim, said by telephone that, in the municipal licensing process, ICMBio should only be notified. In other words, according to Rolim, the federal agency does not need to approve the license.

However, ICMBio’s understanding is different. When questioned through the Access to Information Law, the agency cited the resolution of the National Environment Council (CONAMA) 428/2010, according to which “the licensing of projects with a significant environmental impact, which may affect a specific Conservation Unit, can only be granted after authorization from the agency responsible for administering the unit”.

One of the differences between the two licenses is that, in the case of the state resolution, the so-called Environmental Impact Study/Environmental Impact Report is not required. This is contrary to licensing by a federal agency, which includes “ore extraction” in the list of activities that need to undergo an impact report.

Itaituba’s secretary also said that all 22 environmental licenses issued to the Grota group had been communicated to ICMBio and that he would send a copy of these letters to Repórter Brasil, but nothing has been sent as of the publication of this report. When asked, ICMBio confirmed that it had not received any letters from the municipality.

This report was supported by the Pulitzer Center’s Rainforest Investigations Network. Read more.

*Translation: Fernanda Buffa