Audi, Uber, and 20 other companies offset greenhouse gas emissions using carbon credits from an area where the Brazilian authorities identified deforestation and the use of enslaved workers. In June 2023, 16 workers were rescued from the Sipasa Farm, owned by the company Sipasa, in Moju, northeastern Pará.

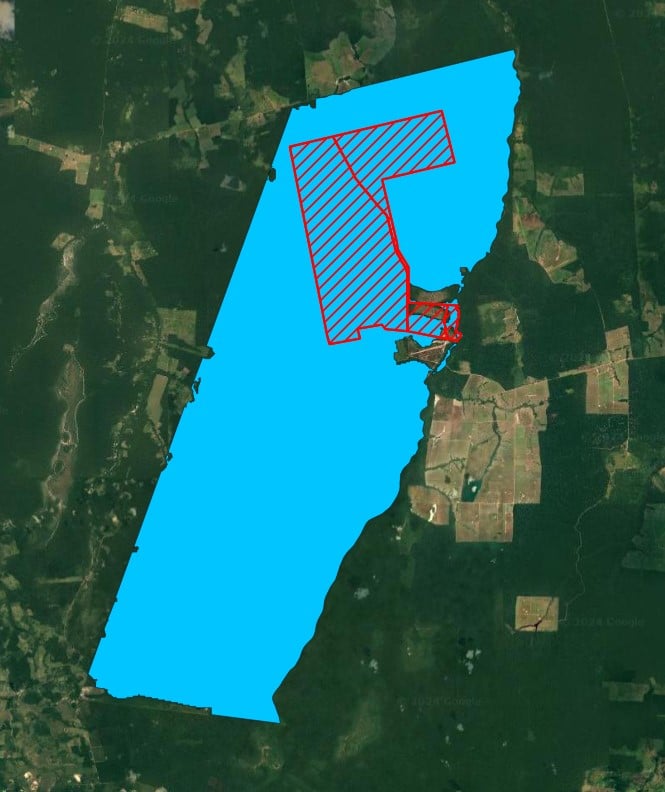

The workers had been hired to clear 477 hectares of forest within an area of the farm belonging to the Maisa Project, which was rewarded for keeping the forest standing. In the carbon market, companies and individuals buy credits from projects that prevent deforestation to offset the emissions from their daily activities.

Uber, for example, used these credits to offset emissions from its operations in Ecuador, the Dominican Republic, and Panama, while Audi Sport offset emissions from its participation in the Dakar Rally competition.

The carbon credits generated by the project and used between 2020 and 2023 amounted to approximately USD 6 million according to an estimate by the London-based consultancy AlliedOffsets, whose methodology is based on market prices. The area to be protected encompassed a total of 26,000 hectares in the Amazon – including the Sipasa Farm, where the workers were rescued.

According to José Weyne Nunes Marcelino, a labor auditor who coordinated the inspection operation, they were housed in a wooden shed “in extremely precarious conditions, with a collapsing floor and parts of the roof missing.”

The inspection report, accessed by Repórter Brasil, also indicates that the dormitory rooms were so hot that the employees preferred to sleep in hammocks in the open air. “At Sipasa’s lodging, we slept in hammocks, there were no beddings, only what I brought. A fan? That never existed where I worked,” confirms Francisco*, a 70-year-old chainsaw operator and one of those rescued in the operation.

There was also no water in the bathrooms – built outside the shed. According to the inspection, the workers showered with a hose and relieved themselves in the bushes. The cook, the only woman among the rescued, had to improvise a bathroom inside the wooden room to shower with some privacy.

In response to the report, Uber stated that it only invests in projects that are “certified, traceable, and auditable” by internationally recognized organizations. Audi stated that it will “seriously follow up on the information” sent by Repórter Brasil but could not provide further clarification at the moment.

Verra, the certifying organization of the project, stated that after being contacted by Repórter Brasil, it decided to “immediately deactivate the project.”

After the publication of this article, the lawyer of the farm’s owner, Sipasa Seringa Industrial do Pará, Adalberto Silva, sent a statement. In it, he states that “during the period of the contract, Maísa has strictly complied with the rules laid down in the contract and with the recommendations of the auditors, and that there is no reason to speak of regular or irregular deforestation within the framework of the project”. It also sets out the reasons for disagreeing with the inspection, which classified the situation found as work akin to slavery.

Read the full statements here.

Nike, iFood, and Giorgio Armani were also clients

Audi used carbon credits from the Maisa Project in July 2023, a month after the workers’ rescue, to offset the emissions from its race cars in the 2022 Dakar Rally. Uber’s use of credits occurred in August 2023, also shortly after the Brazilian authorities’ action on the farm.

Other companies also used credits from the Maisa Project last year, although before the rescue. iFood offset the carbon emissions from carnival events sponsored by the company, and Giorgio Armani Spa used Maisa Project credits to neutralize emissions from a fashion show in Dubai. Nike also used credits from the area in its operations.

The integrity of the Maisa Project had been questioned since 2021 when deforestation was identified within the area, according to reports from the Unearthed and Climate Home News. However, since the project was only definitively terminated now, credits generated in 2020 and purchased until 2022 remained active and were used to offset later emissions.

“If the company buys [the credit], it also contributes to the violations within this property and is fostering slave labor,” points out Andréia Barreto, from the Public Defender’s Office of the State of Pará. For the defender, the flagrant ” demonstrates that the project lacks social sustainability.” Last year, the DPE requested the suspension of carbon credit projects in five traditional territories in the state due to indications of land grabbing.

In a statement to Repórter Brasil, iFood emphasized that “the amount [of credits used by iFood] related to the mentioned project represented less than 0.002% of its total issued,” and stated its commitment to conduct its business with responsibility, ethics, and integrity. Read the full statements from the companies here.

Giorgio Armani and Nike did not respond Repórter Brasil’s requests for comments. The space remains open for their comments.

Lack of regulation concerns social movements

Projects like Maisa are advancing rapidly in the Amazon, but still without established rules. However, Brazil has been moving towards regulating the market.

In June 2023, the government resumed the National Commission for REDD+ – Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation, which includes the so-called voluntary carbon market projects, where companies and individuals can operate. This is the profile of the Maisa Project, whose full technical name is Maisa REDD+ Project.

The Catholic Church’s Pastoral Land Commission (CPT) views the advance of REDD+ projects with concern. In a note sent to Repórter Brasil, the executive coordination of the campaign against slave labor states that it is necessary to “alert and seek to hold accountable the buyers of these carbon credits about the real situation from which these new ‘commercial products’ arise.” The full note can be read here.

Last December, the Brazilian Chamber of Deputies approved a bill that provides for the implementation of a regulated carbon market in the country – a different modality from the business involving governments, not the private sector. The initiative was also criticized by civil society organizations. “The project formalizes the forest carbon Wild West in Brazil,” said Stela Herschmann, deputy coordinator of International Policy at the Climate Observatory in a press release issued by the organization at the time.