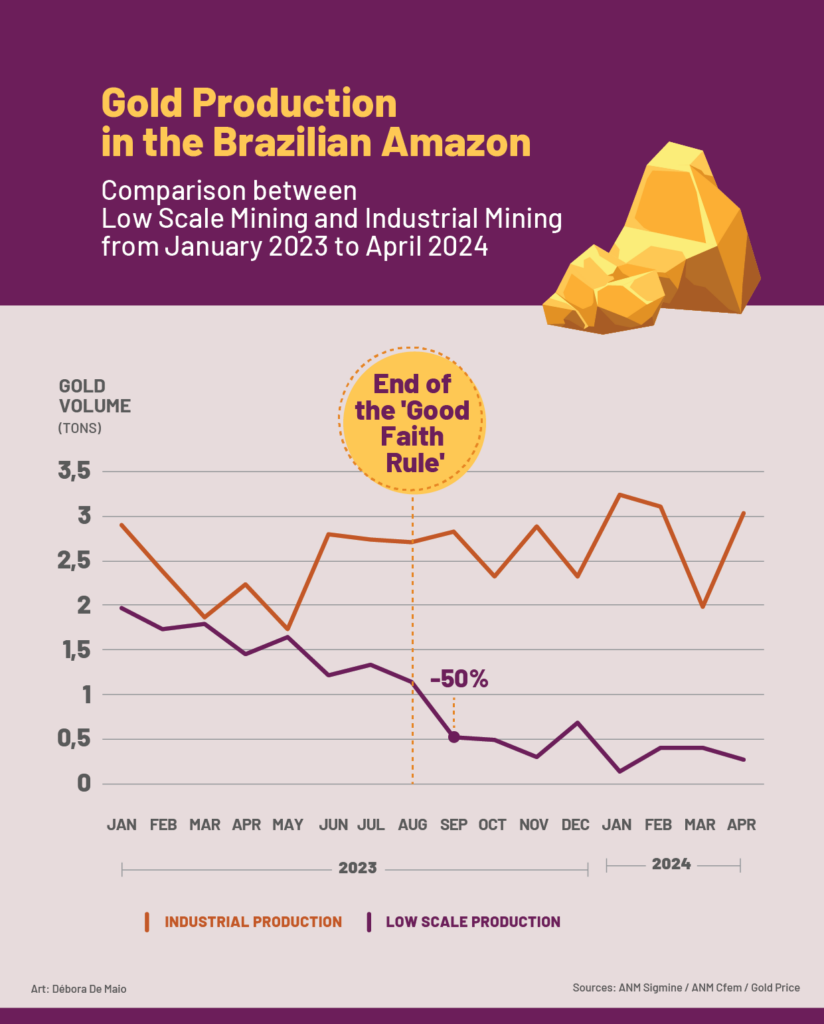

The end of the “good faith rule” in Brazil’s gold trade, cited by experts as a major facilitator of precious metal smuggling, has led to a dramatic reduction in declared volumes of gold extracted from mining operations one year after its implementation. This suggests that legal mining permits were being used to legitimize irregularly produced gold.

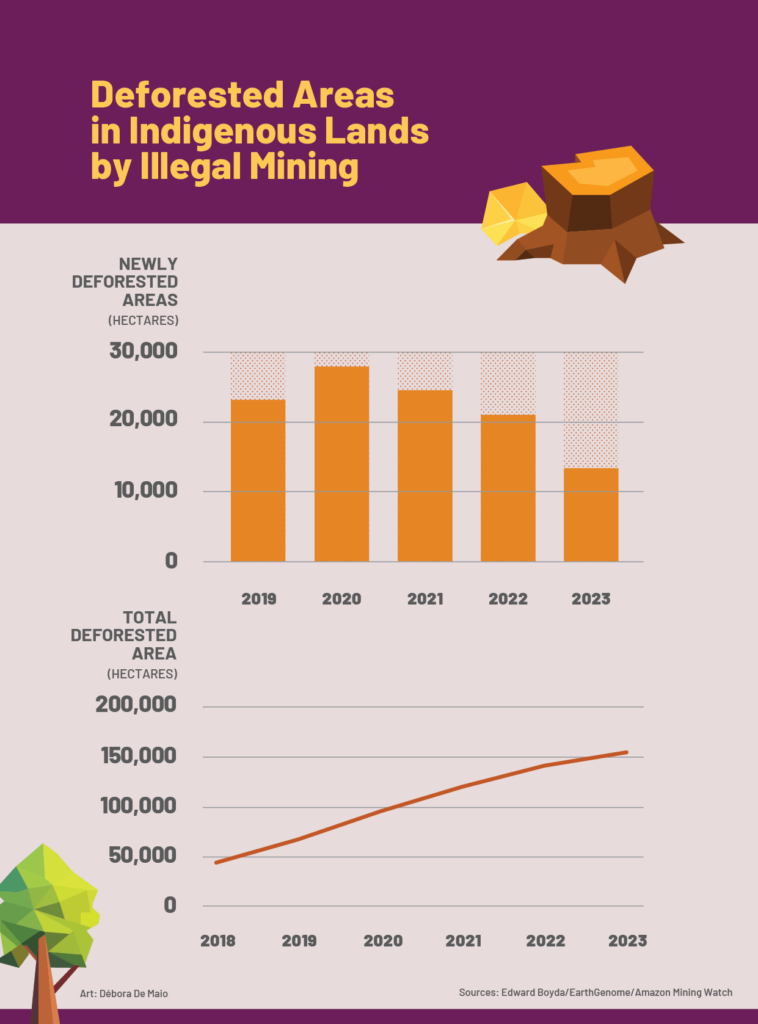

Meanwhile, Brazilian indigenous lands lost over 13,000 hectares of forest to mining in 2023. Although the rate of deforestation has slowed compared to previous years, it indicates that illegal activity persists in the Amazon, where mineral exploration on indigenous lands is prohibited by law.

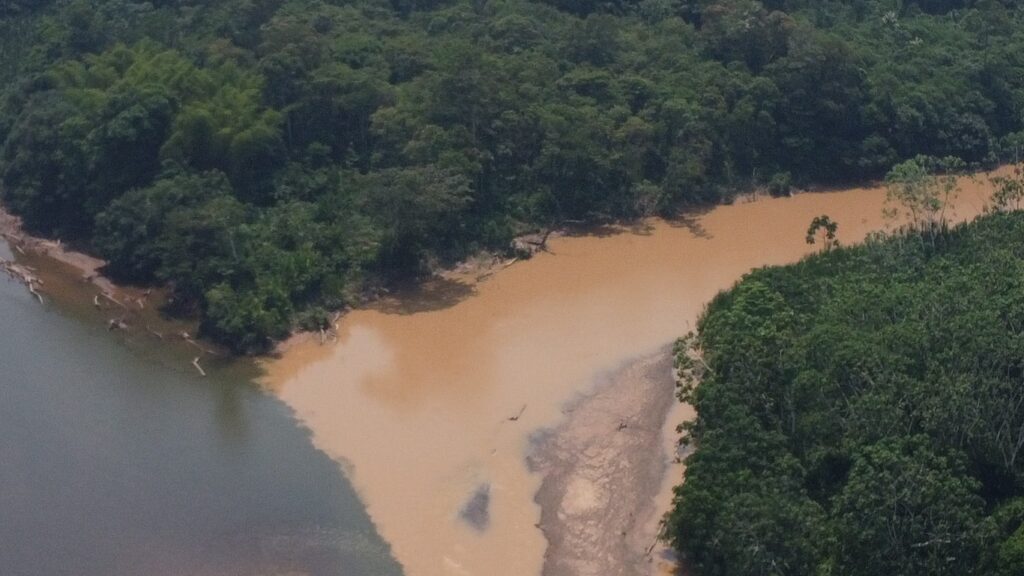

A notable example of the growth of mining in protected areas is the illegal extraction of gold near the Homoxi village in the Yanomami indigenous territory. Satellite images show that the mined area expanded between 2018 and 2023, with experts identifying signs that mining activities continue.

These developments highlight a potential shift in methods of laundering illegal minerals in the country. This is revealed by an exclusive investigation conducted by the international collaboration “Golden Opacity: The Mechanism of Latin American Gold Trafficking“, led by Peru’s investigative journalism organization Convoca, with participation from Repórter Brasil and other outlets in Colombia, Ecuador, and Venezuela.

The “good faith rule” allowed the buying and selling of gold based solely on information provided by miners at the time of sale, reducing the responsibility of the initial buyers, the Securities and Exchange Distributors (DTVMs), regarding the origin of the raw material. However, it was canceled by the Supreme Federal Court last year, resulting in a 73% decrease in declared gold values from mining operations after August 2023, compared to the period before the legislative change.

The number of mining operations declaring production also plummeted: from 344 in January 2023 to just 97 in the same month of 2024. “The transformations in the gold market are not a reflection of a decrease in illegal mining, which was minimal, but of reduced ease in laundering the mineral,” says researcher Rodrigo Oliveira of the Federal Public Ministry of Pará.

Senator Fabiano Contarato (PT/ES), author of a bill proposing the Gold Transport and Custody Guide—a traceability document aiming to enhance control and transparency of the mineral’s production chain—argues that the approval of his bill could provide more oversight of illegal activities in protected areas: “Restricting the commercialization of gold from indigenous lands and conservation units, instituting rules to combat money laundering, and revoking provisions in Law 12,844 of 2013, which weaken oversight, will bring significant progress in combating these crimes.” The bill has already been approved by the Senate and is now under consideration in the Chamber of Deputies.

Brazilian Federal Police seize ‘cold’ gold

Brazil has long been known for laundering irregular gold. Domestically, investigations reveal that before the change in the “good faith rule,” gold was extracted from protected areas—such as indigenous lands—and registered through fraudulent mining processes. In 2021, the Federal Public Ministry (MPF) in Pará called for the suspension of the three main Securities and Exchange Distributors (DTVMs) operating in the country after a study identified the suspected laundering of 49 tons of illegal gold from Amazonian mines between 2019 and 2020.

Internationally, the journalistic investigation shows that Colombian miners often smuggle their illegal shipments via the Puruê River at the Brazil-Colombia border, where the presence of Colombian guerrillas raises alarms and even leads to clashes with the local Navy. In these conflict zones, the mineral is used as currency to purchase other smuggled goods. Meanwhile, illegal Venezuelan gold has established its sales points in Brazil, Colombia, and the Dominican Republic.

However, with changes in legislation and increased operations by control agencies, illegal gold may be taking a reverse route. Last November, the Federal Police dismantled a scheme involving the transport of illegal “cold” gold [unlaundered illegal mineral] to Venezuela. Rodrigo Oliveira of the MPF also noted “an increase in the circulation and export of ‘cold gold,’ to be laundered in neighboring countries or even in consumer centers with more lenient legislation, such as in Asian countries.”

Recently, Repórter Brasil reported that Federal Revenue inspectors identified 5 kilos of undeclared gold powder mixed with a shipment of 15 tons of activated charcoal, which was detained at the Port of Santos (SP) on suspicion of illegal precious metal trade.

“The new electronic invoice and the end of the good faith rule have significantly hindered gold laundering. Consequently, the trade of this illegal gold has shifted to attempts at selling it entirely without documentation, leading to several seizures of gold being transported and traded completely cold, in secret,” says Gustavo Geiser, a forensic expert with the Federal Police in Santarém (PA).

Gold from South America has unknown origins

Three thousand tons of gold exported by Brazil, Peru, Colombia, Ecuador, and Venezuela between 2013 and 2023 have unknown origins. This represents half of all declared exports from these countries (5.9 thousand tons) and signals an unprecedented increase in the volumes of illegal mining exports.

The majority of the discrepancy between gold production and export in these five countries (99%) occurs in Peru, where external sales over the decade totaled 4.4 thousand tons, despite the country registering production of only 1.3 thousand tons. Colombia follows, having exported 59 tons more than its declared production of 559.81 tons in the period, while Ecuador records an excess of 12 tons exported compared to its production (69 tons) between 2017 and 2023, the years with reliable data for analysis.

In Brazil and Venezuela, there are years with more exports than production, but the figures released by both countries have gaps that prevent precise analysis. In Brazil, the period from 2015 to 2021 was analyzed, showing that production exceeded exports by 34 tons. In Venezuela, the balance is 52.6 tons more produced than exported between 2013 and 2023. However, in both countries, illegal mining is gaining ground.

Favored by the lack of control and adequate oversight policies, illegal gold follows paths now uncovered by this joint investigation until it is exported to other continents, concealing its illegitimate origins. Some of this gold ends up in luxury jewelry stores in Europe, in poorly audited destinations like Dubai, Turkey, and India, and in the vaults of well-known technology manufacturers in the United States.

Negligent legislation: a common thread among countries

In Brazil, mining operations are experiencing alarming expansion, a phenomenon that, according to Fabiano Bringel, a researcher at the State University of Pará, results from “a gradual removal of formal legal obstacles that, in some way, disciplined this activity.” This shift occurred particularly after the impeachment of former President Dilma Rousseff (2016) and with the rise to power of Jair Bolsonaro (2019-2022).

For instance, in 2022, a supposed “improvement” of the Brazilian Mining Code was approved, which relaxes the granting of licenses to miners under the argument of promoting artisanal and small-scale mining. Consequently, mineral exploration requests that are not responded to by the National Mining Agency within 60 days are automatically considered approved.

Bringel notes that there is a recent “regulatory contortionism” that has blurred the lines between legal mining and illegal mining. “There are a series of activities that, by their nature, could not even be considered mining, yet they continue to benefit from less protective regulations,” he explains. This has resulted in sophisticated equipment and heavy machinery being seen in these illegal mining zones. Another controversial regulation sets the concession limit at 50 hectares per individual miner, 1,000 hectares per cooperative, or up to 10,000 hectares if the cooperative operates in the Amazon.

In Peru, political power has also directly favored informal mining. Since 2002, a Formalization Law has aimed to get artisanal and small-scale miners to regularize their status and adhere to environmental standards. The initial deadline for compliance was one year, but it has been extended so many times that, 22 years later, regularization is still possible. Recently, a new initiative emerged to extend the deadline once again until 2027. Like in Brazil, these formal mining records have also been used as ghost permits, registering production despite being inactive.

In Colombia, to address gaps in the gold production chain, Congress passed regulations requiring gold and other precious metal traders to apply due diligence criteria. Although it came into force in July 2022, nearly two years later, the measure has yet to be implemented because the Ministry of Mines has not issued specific guidelines to regulate the process.

Political indecision also affects enforcement processes in Ecuador, especially as the incidence of this environmental crime is at its peak. Four years ago, then-President Lenín Moreno decided to merge the three oversight bodies for the mining and energy sectors into a single institution—a failed operation that lost many resources, according to former Minister of Mines Fernando Benalcázar, interviewed for this series. In May this year, current President Daniel Noboa separated the agencies again, and the competencies of the Mining Regulation and Control Agency were reestablished. In 2019, the agency attempted to collect laboratory samples to verify the purity and weight declared by traders in an effort to identify illegal operations. However, the measure provoked industry backlash and was reversed, with controls becoming less stringent once more.

*This article was produced as part of the cross-border investigation “Golden Opacity: Mechanisms of Latin American Gold Trafficking”.

Editorial Team:

| – Coordination and General Editing: Milagros Salazar (Convoca) |

| – Brazil: Hyury Potter and Naira Hofmeister (Repórter Brasil) |

| – Ecuador: Plan V |

| – Colombia: Juan Carlos Granados and Óscar Parra (Rutas del Conflicto / Consejo de Redacción) |

| – Peru: Paul Tuesta, Roberth Orihuela, Milagros Salazar, Gonzalo Torrico (Convoca) |

| – Venezuela: Lisseth Boon (Armando.info), Lorena Meléndez, Ronna Rísquez (Alianza Rebelde Investiga, formed by Runrunes / El Pitazo / Tal Cual) |