MARANHÃO, BRAZIL — Before dawn, Davi* returned to the workers’ quarters at the charcoal factory where he worked in Mirador, in the interior of Maranhão state, in northeastern Brazil. On his day off, he had been drinking in a bar near the Cana Brava Indigenous Territory and returned in an agitated state. Disturbing other workers, including the foreman, he knocked over chairs and made a commotion.

What happened next was brutal.

“He [the charcoal plant manager] punched the young man in the face, slammed his head against a pillar and then began beating him with a broomstick,” recounted a worker who says he witnessed the assault.

The manager is said to have tied Davi’s hands behind his back and restrained him before the crew. He then allegedly photographed the scene and later shared the images to assert his authority. “He would say that it was his way or nothing,” the witness added.

These photographs and testimonies appear in the official report from Operation 216, an inspection by Ministry of Labor officials in July 2021. When the inspection concluded, 11 workers were freed from conditions amounting to modern-day slavery.

ASSINE NOSSA NEWSLETTER

After the assault, the manager reportedly visited other charcoal factories, “showing the pictures and intimidating other workers with threats,” according to statements collected from employees by the inspectors.

The individual responsible for the operation, according to the Ministry of Labor and Employment (MTE), was Sirlei Martins Amaral—known as “Ferinha”—who has repeatedly appeared on Brazil’s official “Dirty List” of employers held liable by federal labor inspectors for slave-like labor practices.

The violence, fearful atmosphere, and exhausting schedule in the charcoal furnaces—all described in federal labor reports—reveal more than isolated brutality. They are part of a supply chain reaching the global market and Toyota, the world’s largest carmaker.

The Japanese manufacturer sold 10.8 million cars in 2024—a slight drop from the previous year, yet enough to remain the top carmaker worldwide for the fifth consecutive year, ahead of Germany’s Volkswagen.

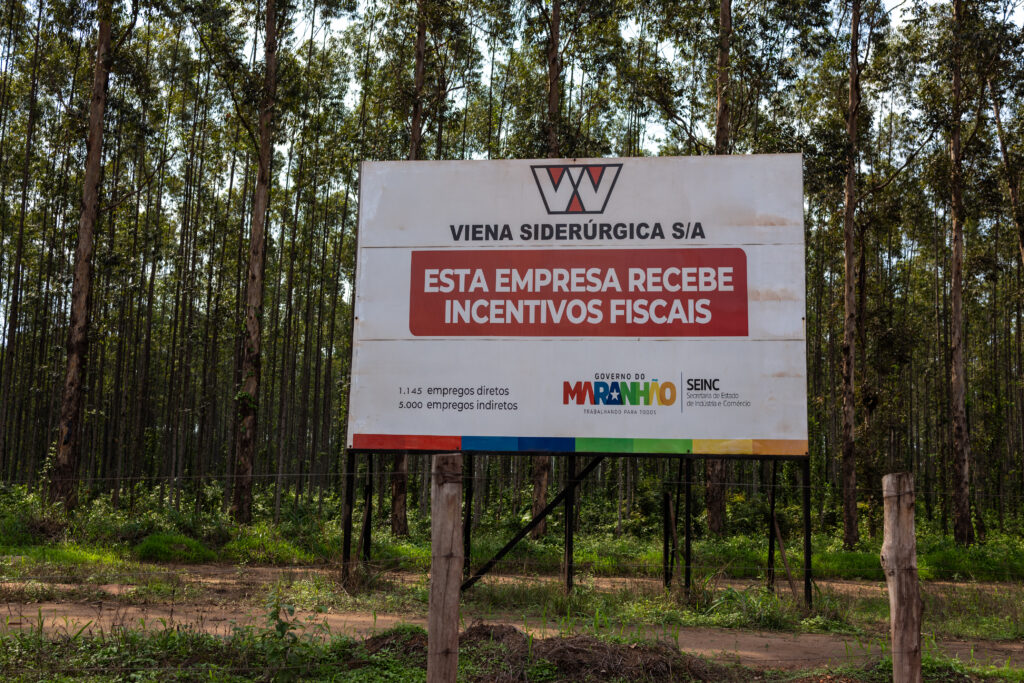

Between Ferinha’s charcoal businesses and the Japanese multinational is Viena, a steelmaker with plants in Sete Lagoas (in the state of Minas Gerais) and Açailândia, in western Maranhão. Viena is the region’s largest charcoal buyer—including the factory where the episode of aggression allegedly occurred. Although authorities formally submitted the complaint to police and prosecutors, no investigation was launched.

Repórter Brasil traveled through this part of the Amazon to document Davi’s story—how he was photographed bound and beaten—and to trace the global trade networks exposed by that long-forgotten image from a 177-page government report.

Brazilian steelmaker shipped pig iron to Toyota in the U.S.

Within minutes of entering a charcoal plant in central-southern Maranhão, the smoke causes your eyes to sting. Soot covers the ground and clings to the workers’ faces. One worker, his entire body blackened with coal dust, said: “This is hard work. But it’s the only thing available here.”

Coal produced by sites tied to Ferinha supplied Viena Siderúrgica. The company’s Açailândia plant is among Brazil’s 40 largest steel manufacturers. There, charcoal is used to smelt iron ore into pig iron—a metal alloy with various applications, including in the automotive industry. According to Viena, 80% of its production is destined for the North American market.

Repórter Brasil examined official customs and port records, which show that Toyota’s U.S. operations are among Viena’s customers.

At least four shipments—totaling 8,000 tons of pig iron—left the mill for Toyota between February and September 2022. These sales happened the year after the documented assault at the charcoal factory.

Repórter Brasil asked Viena about the origin of the pig iron exported to Toyota in the U.S.—whether it came from Sete Lagoas or Açailândia. Through its press office, the company said it could not disclose this information, stating that its commercial agreements with clients and former clients are confidential.

What those involved in the case say

In a statement, Toyota’s office in Brazil said, “Our operations are independent from other Toyota units worldwide and, as such, we have no influence over Toyota Motor North America (TMNA) suppliers.” Toyota USA—contacted multiple times—requested more time to respond but ultimately did not reply to submitted questions.

Viena Siderúrgica said it “repudiates any form of worker exploitation and does not do business with suppliers who breach labor laws.” The company said its business with plants linked to Sirlei Martins Amaral was restricted to units “authorized by the proper authorities” and that, once aware of labor inspections, it removed those suppliers from its chain.

Through his lawyers, Sirlei Martins Amaral (“Ferinha”) maintains he “never condoned such practices” and that “there is no criminal conviction against Mr. Amaral.” The statement says the inspected charcoal factory—where the assault took place—was shut down. Additional points from Amaral’s legal team appear elsewhere in this article.

Full statements from Toyota, Viena and Ferinha’s legal counsel are available at this link.

Labor prosecutors discuss conduct adjustment agreement with steel producer

Ferinha deliberately set up a convoluted business structure to operate his charcoal factories in Maranhão, according to a Labor Prosecutor’s Office (MPT) report.

Multiple companies would operate in tandem—separate only on paper, each with its own registration number and address but sharing the same workers, foremen, wood, and kilns.

“Based on the accounts of workers and foremen, I found that all of Ferinha’s production was destined for the Viena steel mill,” said Luciano Aragão Santos, an MPT prosecutor.

Santos led an inquiry into slave-like labor in Maranhão’s charcoal industry, resulting in a formal investigation of Viena. Beyond eyewitness accounts, he found invoices and receipts charting commercial exchanges between the steelmaker and the charcoal plants.

Prosecutor Santos said Viena oversaw charcoal quality and set purchase prices. In several raids at Ferinha-linked sites, he reportedly found laborers forced to work grueling hours in degrading conditions—which, under Article 149 of Brazil’s Penal Code, may constitute a situation analogous to slavery.

The Labor Prosecutor’s Office is in final negotiations with the steel company for a Conduct Adjustment Agreement (TAC). Among the measures outlined in the agreement are the adoption of human rights due diligence—a process requiring the company to identify, prevent, and remedy risks of violations such as forced labor within its supply chain—economic reparations to victims already identified, and the implementation of effective mechanisms to trace the origin of charcoal used in production.

While steelmakers may not impose abusive labor on direct employees, “they benefit, and profit, from the intensive exploitation of labor in the charcoal factories that supply their operations,” Santos wrote in his investigation report, part of the MPT’s Chain Reaction project.

Ferinha is already well known among Brazilian labor inspectors and prosecutors. In at least seven operations since 2015, he has been linked to charcoal plants charged with slave labor practices, lack of protective equipment, hazardous housing and excessive working hours.

Due to repeated violations, he was detained at the request of the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office in November 2022. Less than a month later, his defense succeeded in having his pretrial detention converted to house arrest with electronic monitoring. Four months later, a federal judge in Balsas (Maranhão) lifted the restrictions. The proceedings ended in August 2023.

Altogether, four companies tied to Ferinha have been fined 19 times by Ibama, Brazil’s environment federal agency, for violations including illegal deforestation and unauthorized use of native wood. The total fines amount to US$7.05 million.

Ferinha’s lawyers assert the 2022 pretrial detention was vacated and the case closed “precisely because there is no evidence to support the charges.” They also claim the environmental notices issued by Ibama are under appeal and do not represent final sanctions.

Ferinha still controls two registered charcoal plant businesses: one in Araguatins (Tocantins) and another in Grajaú (Maranhão), according to the Brazilian Federal Revenue Service. Another six charcoal plants are listed in the agency’s database but are considered inactive.

Ferinha and his businesses have appeared on the official Dirty List of firms linked to slave labor at least five times—most recently this April. After two stages of administrative appeals, the names of employers are placed on this federal list. While this brings no automatic sanctions, banks and companies use it for risk assessments.

Ferinha’s attorneys are challenging his latest inclusion on the Dirty List in court, arguing that it violates fundamental rights—notably due process, the right to a full defense, and the presumption of innocence.

‘The steel mill sets the rules’

On paper, Viena Siderúrgica functions only as a buyer. But according to labor inspection records and the MPT’s investigation, the steel company acted as though it were, in effect, the owner of the charcoal plants.

The MPT claims Viena’s technicians visit the furnaces, set charcoal quality standards, impose penalties for excess coal dust, demand production targets, and communicate directly with Ferinha when issues arise. “They control everything—even how the logs are stacked,” said one foreman interviewed by inspectors.

Invoices gathered by labor inspectors and cited in the MPT report prove a direct supply relationship from Ferinha’s furnaces to Viena’s production line. “At every charcoal factory where I’ve rescued workers from conditions analogous to slavery, Viena is the end customer,” federal labor inspector Ivano Sampaio observed.

Viena makes pig iron using ore from Brazilian mining giant Vale’s Carajás complex in southeastern Pará state. Like all mills in the region’s steel district, its operations depend on the railroad and seaport of São Luís (Maranhão), both run by Vale.

In 2007, Vale suspended ore supply to four steel plants over labor and environmental violations—but Viena was not affected by the temporary blocks.

In a statement, Vale’s press team said, “The commercial relationships established between the parties are governed by contractual clauses that set forth clear commitments regarding human rights.” The statement further noted, “Proven non-compliance with these obligations will result in justified termination of the contracts.” Read Vale’s full statement here.

‘At night, there’s a danger of snakes’

Repórter Brasil visited two charcoal facilities in south-central Maranhão, where the Ferinha-run plant—where the photo of Davi was taken—was based. Narrow, rutted roads wind through remote forest, leading to banks of round furnaces burning nonstop.

The smell of charcoal hangs thick in the air. Black soot covers the earth and equipment. Furnace operators’ faces are streaked with carbon dust. They wear boots and loose helmets, torn trousers and sweat-soaked shirts. They sleep in improvised huts, yards from the flames, close to the smoke and soot.

Production follows the same cycle: native timber, felled on land cleared for grazing cattle or soy fields, is transported in carts (called cambonas) to the kilns. The batches are fired, cooled, sifted, and bagged—each worker responsible for several steps.

“The worst danger comes from the smoke burning your eyes. At night, there’s also a real risk of snakebite. I always carry a flashlight, but it’s risky,” said José Vagner Coelho Souza, 53, one of thousands of workers rescued by federal labor officials in Maranhão from slave-like conditions.

Souza lives in a rural settlement near the town of Grajaú. Investigators found him working exhausting hours with no rest—starting before dawn and laboring until midnight. “We work in the hope of saving a little money, but it’s just an illusion,” he said.

Souza’s experience is backed by the numbers: Maranhão ranks third among Brazilian states for slave-labor rescues—251 inspections since 1995 have saved 3,799 workers.

Many cases are traced to the charcoal business. Often, companies rebrand and swap names, the kilns resume and the same workforce returns to work within months.

“What we generally observe is that people who are placed in these positions, or subjected to these conditions, almost always come from situations of profound social vulnerability,” explained Morgana Meirelles, an attorney at Açailândia’s Carmem Bascarán Human Rights Defense Center.

“It’s a vicious cycle. Workers are rescued and end up back in the same places months later. No education, no assistance, no path to productive employment. It is state neglect drives them straight back into these exploitative systems,” Meirelles added.

Recidivism is all too familiar to Raniere da Conceição, an agent with the Land Pastoral Commission (CPT), which tracks slave labor cases. “These communities have no guarantee of staying on their land. Without policy support, they leave—or are forced to accept such degrading conditions. It’s not a voluntary choice—it’s having no option at all,” he said.

Informal labor is commonplace. Each investigation sends some workers fleeing into the undergrowth. In one raid, a worker reported that bosses warned them to run as soon as authorities arrived: “He told us to hide and stay out of sight until the inspectors left.”

“This is a global chain—but local people bear the consequences. Those buying these products must recognize they are consuming something produced at the expense of suffering and fundamental rights,” said Mikael Carvalho, coordinator of the NGO Justice on the Trails, who lives in Açailândia.

“Look at what’s been done to my son”

Repórter Brasil found Davi’s parents living on a remote farm in rural Grajaú. Their humble wooden house sits among open fields and woods, beside the Grajaú River. The father face bears the traces of a seasoned charcoal worker; he spent eighteen months tending kilns like those operated by his son. He knows the furnace’s searing heat.

“He never said much. But I know what happened. He’s still afraid to talk,” the father said, noting that his son continues to work in charcoal yards nearby. Davi refused to be interviewed, telling his parents he would rather forget what happened.

Davi’s mother learned of the attack, but has never seen the photograph. When shown the image of Davi tied up, she fell silent for several seconds before speaking. “Look at what they did to my son,” she said, her voice choked with tears.

His parents did their best to persuade Davi to leave charcoal work, offering support and even a place to stay. But he insisted on continuing. Fear, they say, outweighs desire. “He keeps quiet. But if he ever decides to pursue something better, I’ll stand by him. He’s my son,” his father said.

No formal complaint was ever filed in the justice system regarding Davi’s assault; it survives only in labor inspection records. The company failed to report it. The foreman was dismissed, but factory operations continued as before.

Viena continued selling pig iron to Toyota—the world’s most prolific carmaker.

Four years after the photographed attack, Davi was again rescued in a Ministry of Labor operation—this time one of 49 workers found in conditions tantamount to slavery at a different charcoal factory in Benedito Leite, southern Maranhão.

*The worker’s real name has been withheld to protect his identity.

Leia também