The race for critical minerals has pushed into the Amazon and reached the United Nations Climate Summit, COP30. As mining firms and officials highlight Brazil’s potential to supply minerals essential for the energy transition, the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office in Pará watches the developments with “concern.”

In an exclusive interview with Repórter Brasil, prosecutor Thaís Medeiros da Costa sounded the alarm over mining expansion and its possible impact on Indigenous peoples and traditional communities. “This new rush carries immense risk for the peoples of the Amazon,” she said.

Minerals like lithium, rare earth elements, copper and nickel are essential for manufacturing high-capacity batteries and magnets that support the energy transition by reducing fossil fuel use. These critical mineral projects receive preferential environmental permitting and financial incentives—like a recent BNDES initiative pledging US$8.54 billion (R$45 billion) to mining for decarbonizing the economy.

Costa sees a “dangerous disconnect” between Brazil’s National Mining Agency (ANM), which authorizes exploration, and environmental agencies that license these projects. She insists that community impacts should be a concern for both.

“A dual review is essential to ensure licenses are properly issued and all legal safeguards respected. ANM fails on many fronts, and this is one of them,” says the prosecutor.

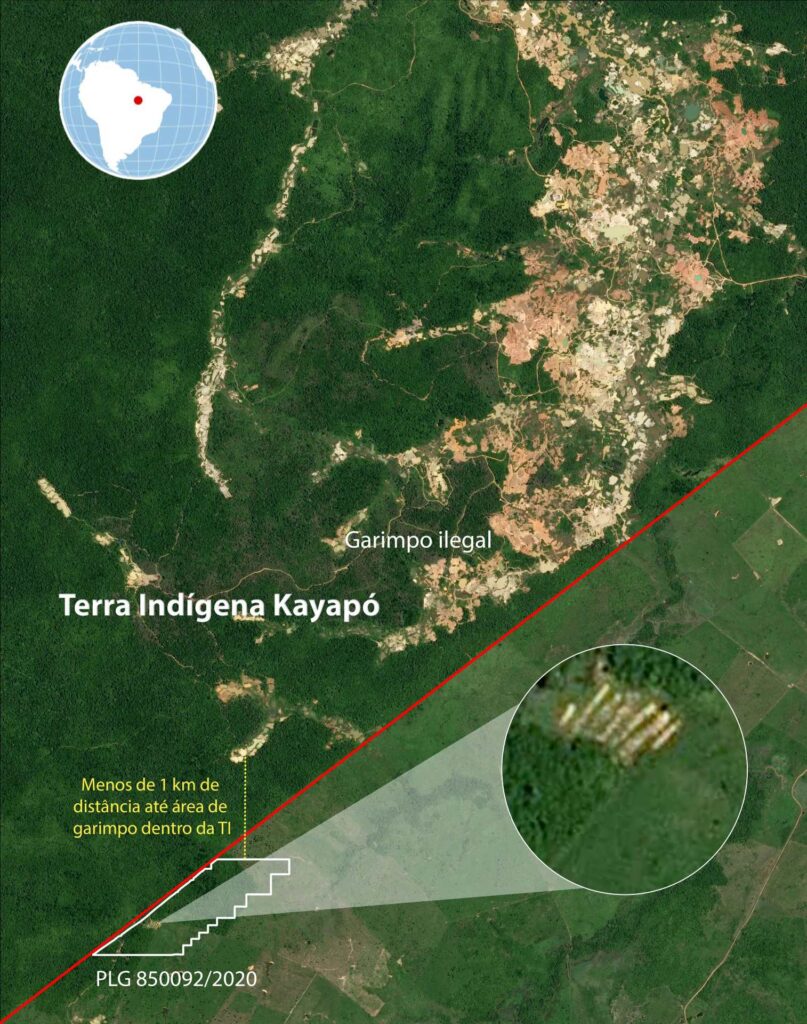

A Repórter Brasil investigation found over 7,700 applications for critical mineral exploration across Brazil’s Legal Amazon. Some are less than 10 kilometers from, or even inside, protected areas—either conservation units or Indigenous and quilombola (rural Afro-Brazilian communities) territories. The law requires consulting affected communities in these cases, but the prosecutor says this often does not happen.

In August, Costa filed a lawsuit to revoke a gold mining license in Altamira, Pará. The suit points to “serious flaws” in environmental assessments and a lack of free, prior and informed consultation with the Kayapó of the Baú and Menkragnoti Indigenous Lands.

ASSINE NOSSA NEWSLETTER

Read the interview:

Repórter Brasil: How does the Public Prosecutor’s Office (MPF) in Pará address illegal gold prospecting and mining?

Thaís Medeiros da Costa: Mining in Pará is a major concern for the MPF. This applies to legal operations—which sometimes have flawed environmental permitting or skip consultations with traditional peoples and communities—and to illegal mining.

The Munduruku Indigenous people suffer daily harm from this mining.

Although their lands are officially recognized as an Indigenous territory, the Munduruku endure persistent invasions by outsiders who exploit weak state enforcement to extract minerals. Such artisanal mining is simply not permitted on Indigenous land.

What are the main impacts of mining?

Mining gravely damages environmental resources—water, soil, air—and these impacts accumulate over time.

Is there a way to mitigate or reverse these impacts?

Undoing environmental harm caused by mining or illegal prospecting is extremely difficult. The MPF has worked with [environmental regulator] Ibama and the Ministry of the Environment and has seen firsthand the challenge of restoring these areas. Enforcement actions may expel invaders, but devastation remains. Repairing this damage is a challenge the government has yet to solve. This must be considered when authorizing mining, as there is still no viable solution to these impacts.

How does the MPF view the push for critical and strategic minerals?

The MPF views this new rush with concern, as Brazil’s economic logic is to approve projects first and ensure feasibility later. This must change: viability should be assessed before decisions are made. I believe this new rush could be deeply harmful to the people of the Amazon and will likely lead to close scrutiny from the Public Prosecutor’s Office.

Such growth will bring environmental impacts. The government must ensure economic development follows legitimate, robust legal channels—otherwise it is invalid, illegitimate and infringes on rights.

Tin is considered strategic for the energy transition. There are reports of illegal mining for cassiterite—the main ore for tin—in the Tapajós basin near Munduruku Indigenous Lands. What is the situation in this region?

The outlook is troubling. Mining brings land pressure, invasions and threats. As cassiterite mining intensifies in the Amazon, communities face serious risks and real losses.

The Brazilian Constitution prohibits mining on Indigenous lands unless authorized by Congress and only after consulting affected communities. Repórter Brasil’s investigations show mining processes near these territories—some less than 10 kilometers away, within areas directly impacted by mining. How does the MPF respond?

In August, my office issued a recommendation—using Ordinance 60, an inter-ministerial rule—calling for mining permits (PLGs) within 10 kilometers of Indigenous lands to be canceled or not renewed. This response to poor environmental licensing, lack of input from FUNAI (Brazil’s National Foundation for Indigenous Peoples), and the absence of consultation with Indigenous communities.

The ANM (National Mining Agency) is the government agency that approves mining operations. How did it respond?

The ANM has repeatedly said it is not responsible for checking whether environmental licensing has been carried out correctly, or if communities have been consulted in a free, prior and informed way. It claims it issues titles properly under existing rules.

There is a very dangerous gap between the agency authorizing mining and the one responsible for environmental oversight—this cannot continue. An environmental license alone is insufficient; a double-check is needed to ensure permits are sound and all the legal guarantees have been respected. ANM fails in many respects, and this is one of them.

According to the MPF, can mining take place within this 10-kilometer zone around protected areas?

Not without consulting Indigenous communities, as required by ILO Convention No. 169 and Ordinance No. 60 [which mandate consultation during environmental licensing]. Within this buffer, impacts are presumed, though there may also be impacts beyond 10 kilometers.

ANM may authorize mineral research before environmental permitting begins. This happened in a case reported by Repórter Brasil, when ANM allowed rare earth research inside a quilombo community in Tocantins. Why might this be a problem?

There is a distinction between approval types. Research authorizations undergo a much simpler permitting process, which is not an environmental licensing procedure. Authorities rely on this premise to either waive environmental licensing entirely or so greatly simplify the process that communities are excluded and activities can begin without a license or consultation.

Brazil’s mining regulations are old and need reform. If the government wants to explore mineral exploitation, it must review its regulatory framework to guarantee maximum environmental protection, uphold restoration duties, and guarantee the participation of affected peoples in the process.

This reporting was supported by the Pulitzer Center’s Rainforest Investigations Network.

This report was produced by Repórter Brasil as part of the Collaborative Socio-Environmental Coverage of COP30. Read the original article here.

Leia também