The Teles Pires hydroelectric power plant, built in the Amazon rainforest on the border of Mato Grosse and Para, will begin generating energy while trees rot in its reservoir. The debris, consisting of branches and logs from chestnut, mahogany, and other tree species, can be seen floating in the lake created by the plant. The rotting vegetation will likely result in increased fish mortality and methane gas emissions, which is at least twenty times more potent than carbon dioxide in contributing to the greenhouse effect. This impact is inexcusable for a company that presents itself as a “clean, renewable, and environmentally friendly source [of energy].”

That company is called Teles Pires Hydroelectric Company, a consortium formed by Neoenergia (50.1%), Eletrobras Furnas (24.5%), Eletrobras Eletrosul (24.5%), and Odebrecht (0.9%). The power plant is part of the Growth Acceleration Program, the flagship infrastructure program of the Brazilian government.

Photos taken of the plant site reveal the company’s failure to comply with the regulatory requirements for its operation as stated in the Deforestation Plan: namely the proper removal of vegetation from the area to be flooded. In addition to methane emissions, these violations result in large-scale timber waste. Eight, now flooded, log landing sites contained timber that should have been sold or used for the project itself but is now rotting in the river instead. Teles Pires Hydroelectric also left trees in areas that should have been completely clear cut, including on the banks of the Paranaíta River, and failed to remove the necessary vegetation on the islands and edges of the Teles Pires River.

Methane Plant

The main consequence of the errors made by Teles Pires is the increase in methane emissions. Methane is generated when an organic substance decomposes without oxygen, as is happening along the bottom of the hydroelectric plant’s reservoir.

This phenomenon is studied closely in Brazil by biologist Philip Fearnside, a researcher at the National Institute of Amazonian Research (INPA). He calls dams in tropical countries “methane plants” because of the way they emit gas steadily over the years. The problem is common for all dams in Brazil, but was aggravated in the case of Teles Pires due to the large amount of trees and debris left in the reservoir.

Fearnside points to an additional source of methane in the reservoir: the shrub that grows in abandoned areas, known as juquira. Since the largest part of the reservoir’s vegetation was removed six months prior to filling it, juquira grew in the locations trees had formerly occupied. When flooded, all the vegetation below the water level becomes methane.

Finally, seasonal shrinking and swelling of rivers will also contribute to methane emissions, according to Fearnside. The vegetation along the river banks is not adapted to remain under water for parts of the year, and thus will regrow during the dry season and decompose, generating the toxic gas during the wet season.

Wood Thrown Away

The company’s actions are also detrimental to the regional economy.

The wasted timber could have been processed by certified sawmills and sold legally, as well as meet the region’s timber demand. Now those supplies will have to come from elsewhere. In an email correspondence, Teles Pires claimed that they “relocated and removed” the logs with commercial value from that area to be flooded. Upon further questioning, the company did not provide additional information about the timber sales.

patio_novoThose living in Paranaíta, the municipality containing the largest part of the reservoir, also miss out on benefits of certain public policies, like loans to farmers, because the city is on the Ministry of the Environment’s “black list” of cities with the highest deforestation rates in the country. The deforestation is concentrated in the soy expansion area near where the dam is located.

Patches of pink indicate deforestation near the plant (which is marked with a yellow dot).

Regulatory Oversight

As the federal environmental inspection agency, IBAMA should have detected Teles Pires’s violations sooner, but its technicians didn’t catch them until February, 2015, nearly three months after authorizing operations in November of 2014. According to the report signed by the technical agency, “the reservoir accumulation clean-up was carried out in an undiscerning and nearly negligent manner.”

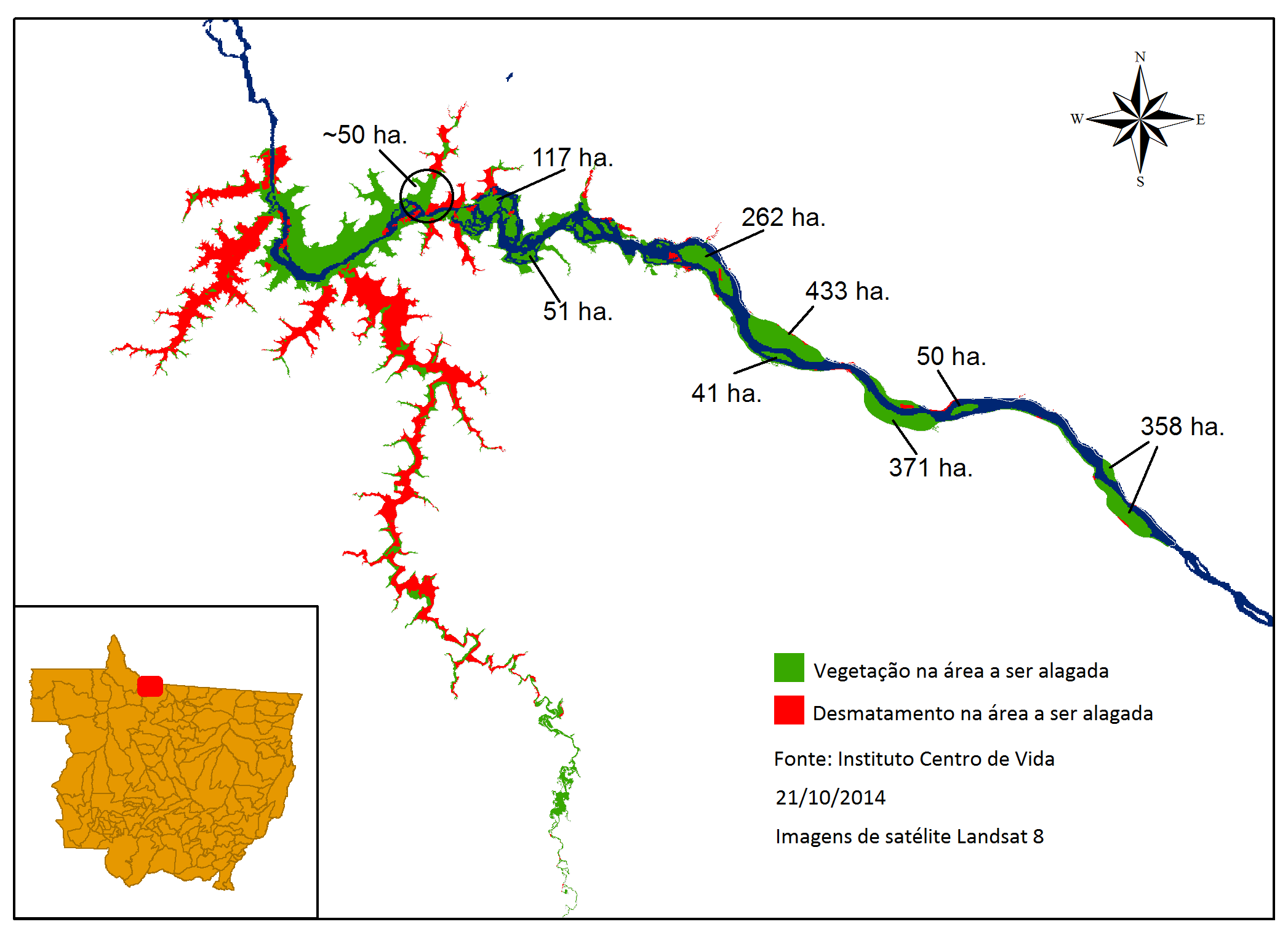

Prior to IBAMA’s inspection, the power plant’s violations had been flagged by the Instituto Centro de Vida (ICV), a non-governmental organization that is monitoring the impacts of Teles Pires. ICV revealed the plant had not removed even half of the vegetation from the site in October 2014, less than a month before it received authorization to fill the reservoir. As a result, 6,200 hectares of vegetation were flooded. (Click here to download the map created by ICV).

The forest inside the Teles Pires reservoir. Red represents the area where vegetation was cleared, while green represents the areas where vegetation should have been removed but wasn’t.

Questioned by Repórter Brasil, the press office of the Teles Pires Hydroelectric Company responded that they are taking “the additional measures necessary or required by the environmental authorities, including cleaning the reservoir” (Read the plant’s full response [In Portuguese]). When asked about the delay in inspection, IBAMA stated that it was completed within the “usual” time frame (Read IBAMA’s full response [in Portuguese]).

A Project with Problems

Even if followed exactly, the plant’s Deforestation Plan will not be strong enough to contain the environmental impacts. The Plan, which was prepared by Teles Pires and approved by IBAMA, requires only 58% of the vegetation to be removed from the 10,700 hectares of land before flooding. According to experts interviewed by Repórter Brasil, this percentage is at odds with other recently approved hydroelectric plans that require all vegetation to be removed.

“Fifty-eight percent has no scientific significance. IBAMA discussed different scenarios with the company and arrived at a number based on what would be more economical for the company,” said Brent Millikan, program director for Amazon International Rivers, an NGO that monitors the impacts of hydropower worldwide. “There has been no open dialogue with the scientific community; it is purely a discussion between IBAMA and the company. And IBAMA is not immune to political pressures.”

The scientists weren’t the only ones not consulted on the details of the plant’s environmental plan, the local population affected by the project was left out as well. “The discussion reached the communities too late; nobody knew anything [about how serious the deforestation would be],” says João Andrade, Forest Governance Project Coordinator for the Instituto Centro de Vida.

Vegetation removal from the reservoir area. The areas on yellow show the deforestation on the islands and along the shores of the Teles Pires’ river.

History Repeated

Teles Pires will not be the first hydroelectric power plant to turn into a “methane factory.” The same problem occurred with the Santo Antônio plant, also in the Amazon.

“Everyone knew that it was happening, taking a boat out on the river was enough to notice it. The problem is that IBAMA does not monitor and enforce the law,” says Arthur Moret, a physicist at the Federal University of Rondônia. “The company only removes the wood with market value. If it has no value, they leave it there.” According to Moret, this is a general problem in the construction of hydroelectric power plants in Brazil.

Built 25 years ago, the Balbina power plant is the best illustration of this problem. The region that was flooded to the north of Manaus had the highest number of trees left standing within the lake. Fifteen years after being built, in 2005, the plant was emitting ten times more methane than a coal-fired thermoelectric power plant would generate with the same energy potential, according to a study done by the INPA. The extent of Balbina’s disaster shouldn’t be repeated on the same scale however, since the area of Teles Pires’ reservoir is smaller and its turbines are more efficient, resulting in less water retained on site.

On the other hand, Teles Pires is already creating environmental problems, even before its five turbines are up and running. The power generation is delayed by more than six months because the transmission line that will connect it to the national grid is not ready yet. The Ministry of Mines and Energy and the plant don’t know when the problem will be solved. Today, the Teles Pires is a hydroelectric plant that does not generate energy—just methane gas.

This report originally appeared on Repórter Brasil in portuguese. It was translated by Global Forest Watch and published in English on their website.