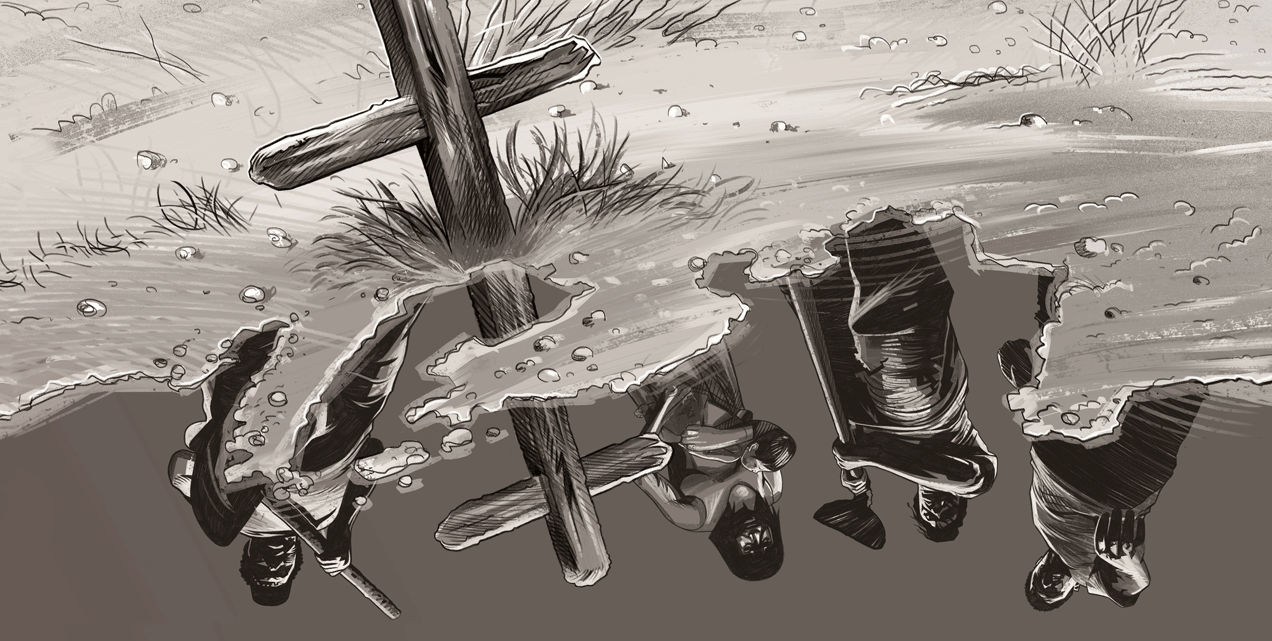

Even before the end of the first half of 2017, three major tragedies in rural Brazil had left their mark in the country’s history. In the state of Mato Grosso in April, nine agricultural workers were killed with particular cruelty. In May, an attack on the Gamela indigenous people, in the state of Maranhão, left two victims with severed hands, five with bullet wounds and another fifteen injured. The third case, also in May but in the state of Pará, was a violent police operation that resulted in the killing of ten landless laborers. “The police turned up shooting,” said witnesses who managed to escape.

The three cases occurred within the context of land disputes, but this is not the only link between them. Repórter Brasil visited all three sites to investigate the attacks and discovered another common trait that is even more alarming: the foreboding tone. In each case, there were signs that the violence was waiting to happen. Some of the victims asked for help from the authorities before the crimes were committed. The survivors are still asking. In the cemetery in Mato Grosso, where five of the workers were buried, the gravedigger dug extra graves in preparation for the next massacre.

The cruelty of the attacks is shocking, but not surprising for anyone who has accompanied the escalation of rural violence.

To keep track of this situation, we have launched a multimedia special called Rural War. In it, we investigate the motivations for the attacks, the context in which the crimes have proliferated, the stories behind the numbers and the links between this violence and the productive sectors that supply the big cities of Brazil and the world. The series, illustrated in comic book language, also mixes photos, videos, audio and infographics within the reporting.

The year 2016 has already gone down in recent history as the one registering the highest number of deaths caused by rural disputes of the past 13 years. There were 61 fatal victims. The brutality of the conflicts in the first half of this year suggests that 2017 could be even worse. “We are seeing in rural areas of Brazil an escalation of the conflict that has always been present in the history of the country,” said Jurema Werneck, executive director of Amnesty International in Brazil.

Nearly a million people were involved in more than 1,500 conflicts over land, water or labor, according to the report Rural Conflicts published by the Catholic Church’s Pastoral Land Commission (CPT). This is the highest figure in Brazil since 1985 and is equivalent to the number of Syrians who are internally displaced due to the ongoing civil war.

Part of the blame for the escalation of violence is the lack of action by the State. Or worse: the actions that only strengthen one side of the dispute, the rural landowners.

In December 2016, in the midst of the escalation in violence, the government of President Michel Temer abolished the National Agrarian Ombudsman, the only federal agency responsible for mediating rural conflicts. After protests from social movements, the agency was recreated under a new administration. In 2017, legislation was proposed by the agribusiness caucus in Congress proposing that agricultural laborers could be paid in just food or accommodation.

While violence is also on the rise against indigenous and traditional peoples, measures are being debated in Brasília to make changes that weaken these populations. In January, the Ministry of Justice created a group that gives powers to government representatives outside the National Indian Foundation (Funai) to determine the limits and deny recognition of indigenous lands. Until this point, the Ministry had followed the technical guidance of Funai. In March, the new Minister of Justice Osmar Serraglio, who has close ties to agribusiness, declared “land doesn’t fill people’s bellies” in an interview on the indigenous situation with the Folha de S.Paulo newspaper. Serraglio later stood down as minister in May.

Set up in late 2016, the Congressional Inquiry Commission on Funai and the Colonization Land Reform Agency (Incra) released its final report in May of this year. The document recommended the indictment of more than 90 people, including anthropologists, indigenous representatives and even federal prosecutors who work on the defense of the rights of indigenous peoples and agricultural laborers.

Brazil is the world leader in murders of environmental activists, according to the NGO Global Witness, which for more than two decades has been studying the links between natural resource exploration and conflicts, among other things. Between 2002 and 2013, the NGO documented 448 killings of Brazilian defenders. The CPT report portrayed the same situation. The number of cases of violence against people jumped from 615 to 1,079 between 2007 and 2016. Cases of criminalization rose 185%. “They have institutionalized the struggle for rights as a crime in Brazil, as if people who protest are criminals,” said Cesar. “When the state is more repressive, it grants a license for violence and legitimizes paramilitary actions,” he said.

The brutality of the violence in rural Brazil was addressed in the United Nations in May 2017. “We are concerned about the increase in attacks in Brazil against human rights defenders. The State needs to deal with the impunity,” said Zeid Ra’ad Al Hussein, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights. The statement was made a week before Brazil was denounced in Geneva for its social policies in recent years. The UN adopted a strategy of “naming and shaming” by focusing on the violations committed in the country. In this case, it focused on indigenous rights, which are now facing the largest offensive since the military dictatorship. In June, special rapporteurs from the UN and the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights declared that “the rights of indigenous peoples and environmental rights are under attack in Brazil”. The response of the Brazilian government, which is already weak internationally, was worse than the analysts could have predicted. In a press release, the Ministry of Foreign Relations called the statements of the rapporteurs “unfounded”.

“The situation is catastrophic,” said Márcio Meira, former president of Funai. “The government is committing atrocities with rights that have been secured at great cost since 1988.” In Meira’s opinion, indigenous peoples are always the first to feel big changes. “This means that, later, the tragedies will befall other vulnerable groups, such as agricultural workers.”

According to Werneck, of Amnesty International, the solutions are not simple, but they do exist. She cited the Constitution of 1988, which established a time frame for the demarcation of indigenous lands. “Look how much time has gone by and nothing has come of this commitment by Brazilian society and obligation of the State. The land demarcation process is too slow and it is also being set back by endless legal appeals,” she said.

Combating impunity in rural conflicts is also a priority to stop the loss of life. According to data from Amnesty International, thirty of the forty municipalities in southern Pará have an impunity rate of 100% when it comes to murders of agricultural laborers over the past 43 years. “We need to stop the threats and insecurities, put an end to the impunity for crimes related to disputes over land and natural resources, and make progress on the land demarcation and titling processes.”

If you know of a story that needs to be told in this special series, email Repórter Brasil at [email protected] and write “conflicts” in the subject line.