In July, a major policy to combat global warming was announced by BlackRock, the world’s largest investment fund manager. The company said it would take concrete action against at least 53 companies for their inaction regarding global warming and place 191 others under observation.

Upon launching the project, the company’s CEO, Larry Flink, announced that the climate crisis will completely change finance, and “companies, investors, and governments must prepare for a significant reallocation of capital.”

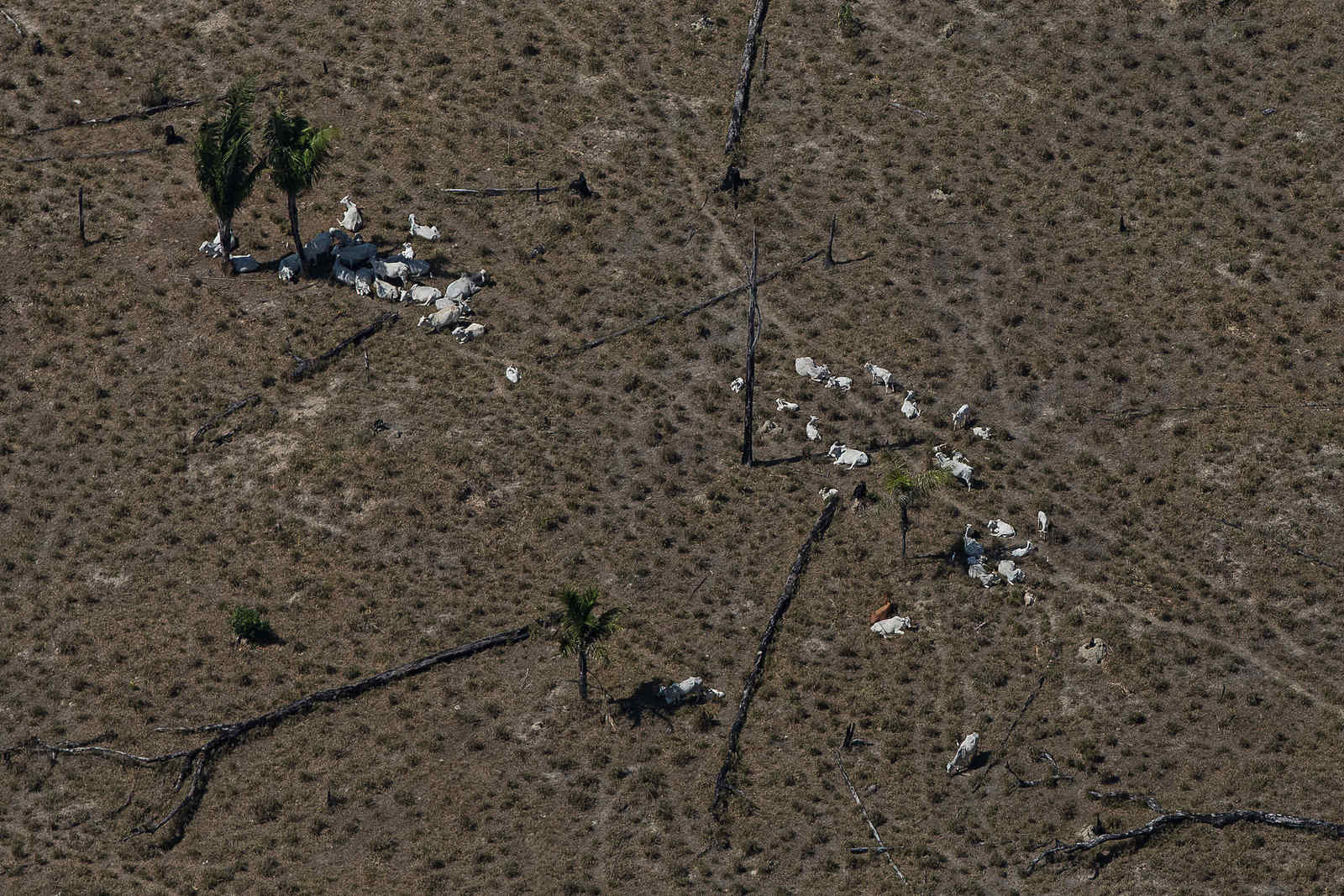

But the announcement left out one of the major drivers of global warming: the meat industry, which is the main cause of deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon. The words cattle and deforestation are missing from the 30 pages of the report in which BlackRock describes the actions it is taking to combat climate change. The company omitted its stake in JBS, the world’s largest meat exporter.

Part of the investments in the Brazilian multinational are made through a BlackRock fund that “favours companies with less production of greenhouse gases.” The fund in question has 53 million Brazilian reais ($9.8 million) in equity and invests in companies listed on the Carbon Efficient Index (ICO2) created by the Brazilian Stock Exchange and the state development bank BNDES. The index is supposed to include companies with “transparent practices regarding their greenhouse gas emissions.”

In May this year, Blackrock became JBS’s third-largest shareholder – behind J&F Investimentos, controlled by the company’s founders, and BNDES. A series of reports and studies published this year showed cases of illegal deforestation among JBS suppliers, even though it pledged not to buy cattle from deforesters more than ten years ago. JBS has repeatedly denied the problems found in its supply chain.

“BlackRock has not by any means done everything they should on energy issues – they are still the world’s largest investor in coal for starters – but they have been much more vocal about energy than they have about agribusiness,” says Jeff Conant, director of the forest programs at Friends of the Earth. “In general, investors have been slow to address the crucial role that forests and land use play in driving the climate crisis, and have faced much less pressure on these issues.”

Focus on energy over agribusiness

BlackRock is a major investor in three out of the 25 largest companies at risk of deforesting in the world, according to a study published by Friends of the Earth US and Amazon Watch. In addition to livestock, the study also looks into investments in industries such as palm oil, rubber, and grains. Despite the importance of agribusiness in climate change considerations, the company’s recent announcement that it will combat global warming was entirely focused on companies linked to the energy and infrastructure industries.

Before announcing measures on global warming, BlackRock released a new sustainability policy for agribusiness. Even in its policy for the segment, livestock is not addressed, and deforestation is mentioned only twice. In reference, the firm asks “companies to disclose any initiatives and externally developed codes of conduct, e.g. committing to deforestation-free supply chains, to which they adhere and to report on outcomes, ideally with some level of independent review.”

Repórter Brasil asked BlackRock if any measures had already been taken regarding its investment in JBS. A spokeswoman said the company engaged “with JBS and others to discuss their policies and practices on issues specific to operating in the Amazon Basin, such as land use and supply chain management, and to hear their views on the long-term climate-related risks for the agricultural industry associated with accelerated deforestation.

“Since those engagements last year, we have continued to closely monitor these companies to assess their operational standards and progress, including implementing their sustainable land use policies,” she said.

BlackRock also stated that it has taken measures related to JBS’s supply chain where there are cases of deforestation. “We discussed JBS’s efforts to eradicate deforestation throughout its supply chain after the company provided an update on these efforts and progress of its advanced monitoring capabilities of supplier farms in the Amazon. We are closely monitoring progress and disclosures.”

JBS investment sold as ‘environmentally responsible’

Part of BlackRock’s investments in JBS is offered to its customers as a “sustainable” option. JBS’s shares are part of a BlackRock fund that manages investments linked to the Carbon Efficient Index (ICO2). It is advertised on the company’s website as a fund that “favours companies with less greenhouse gas generation” and that brings a “low-cost, socially responsible investment solution.”

ICO2 is a stock index. Known in the financial markets by the acronym ETF (Exchange Traded Fund), these indices combine, into a single product, shares of many companies – in this case, companies claiming to have a low carbon footprint.

The main criterion companies have to meet in order to enter ICO2 is an annual inventory on greenhouse gas emissions. The inventory, however, focuses only on companies’ direct operations. Emissions associated with their suppliers are not considered.

BlackRock manages a fund that replicates this index, with shares of all the companies included in it. So through BlackRock an investor in search of sustainable options may come to invest in a company whose suppliers are involved in cases of illegal deforestation.

BlackRock says that as an asset manager it cannot replace a company’s stock with other index chosen by its customers. “BlackRock’s ETFs track the investment results of third-party indices to which our clients themselves choose to allocate their assets,” BlackRock said.

But BlackRock could enforce sustainability policies even in the case of ETFs, argues Moira Birss, director of climate and finance at Amazon Watch. “BlackRock likes to hide behind the excuse of the ‘passive’ index fund model, under which ETFs fall. However, it’s more a question of ‘will not’ rather than ‘cannot’, because BlackRock ignores the many ways that index fund purveyors have multiple choice points at which to apply sustainability policies.”

According to Birss, asset managers can exclude certain companies from indexes. “Even if a certain company, like JBS, remains in a particular index fund, asset managers like BlackRock maintain power to pressure companies to improve their policies – though to date BlackRock has not demonstrated that it is effectively using this power,” Birss added.

BlackRock says it is engaging with stock index creators “to expand sustainable options for investors” and has pledged to double the number of sustainable funds for its clients at a global level in the years to come.

BlackRock under pressure for change

BlackRock has been under pressure to change its investments in agriculture. Last year, US congress members issued a letter in which they questioned the company’s actions regarding deforestation in the Amazon.

“It is incumbent upon US financial institutions to take a firm stance by ceasing all of their financing of that destruction and set a strong example for other institutions to follow,” Democratic Representative Rashida Tlaib said in the letter.

Last year, indigenous lawyer Luiz Eloy Terena, from the Coordination of Indigenous Peoples of Brazil (APIB), attended the company’s assembly in New York where he spoke about the impacts of the its investments in the Amazon. Representing a shareholder, he addressed BlackRock’s CEO.

“Pressure to open new areas to agricultural expansion and illegal logging caused approximately 150 million trees to be cut in [the Amazon] region alone,” said the lawyer, citing BlackRock’s investments in JBS and Bunge, the largest soy buyer in the country. “Due to this type of destruction in our territories and ways of life, we came here to warn you about the risks entailed by this type of investment.”

APIB wants BlackRock to demand JBS and other companies in which it holds shares to provide more supervision of their supply chains and restrict purchases of commodities produced on properties located in indigenous lands or operating in conflict areas. “We understand that as the least a company that considers itself sustainable has to observe [their suppliers] at this moment,” says Terena.

For Shona Hawkes, a senior consultant at Global Witness, banks and investors should demand that governments pass laws compelling them to do due diligence before making investments. “As long as the status quo allows banks and investors to profit from activities linked to deforestation, it’s hard to take their promises for change seriously.”