In the hands of a Federal Police forensic expert, a 1 kilo gold bar is the size of a cell phone. “It’s more than R$300,000 that fits in your pocket,” says the expert, who prefers not to be identified, from the police’s Criminalistics Institute in Brasilia.

The ease with which gold can be sold anywhere in the world, coupled with the fragile control of this market in Brazil, explains why the mineral is increasingly targeted by criminal organizations for money laundering, especially from drug trafficking.

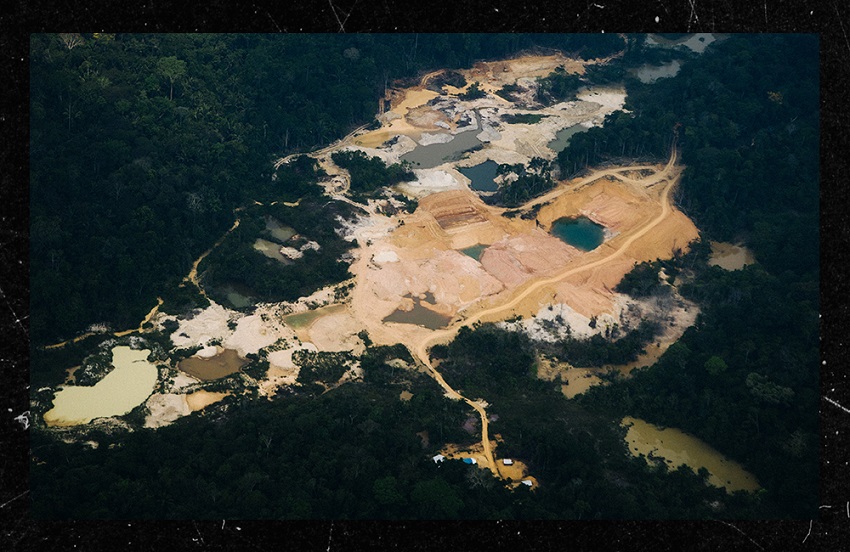

In the Amazon, the cartels took advantage of how Jair Bolsonaro government’s cast a blind eye to illegal mining and invested in so-called “narcogarimpos” – a model in which drug traffickers use money from the drug trade to finance illegal gold extraction and launder millions of reais.

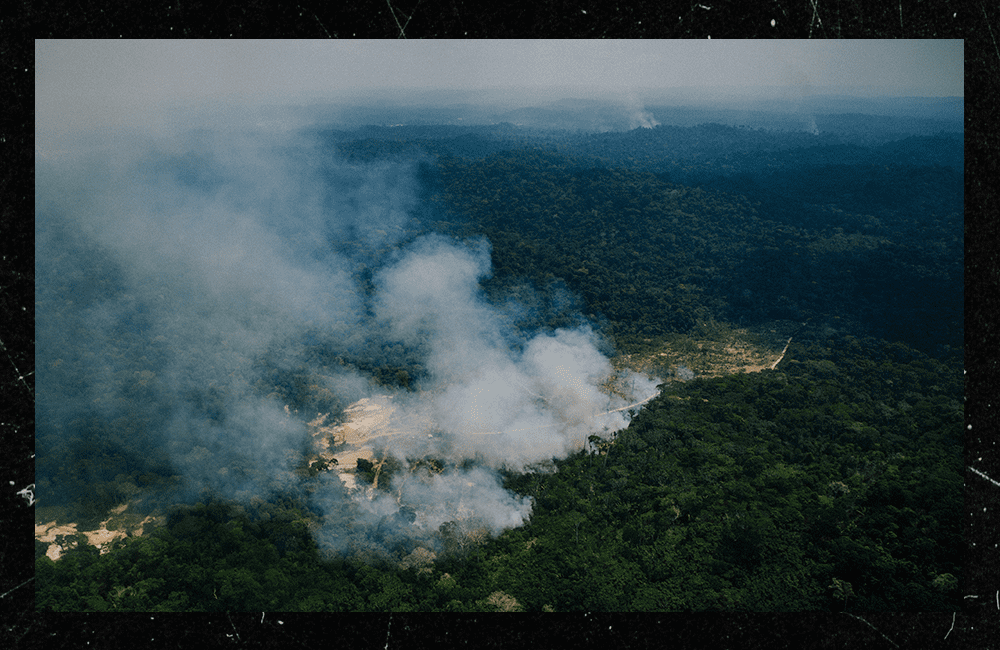

The combination of gold and powder also stimulates other environmental crimes, such as illegal logging and the grabbing of public lands, activities that also receive funds from trafficking. This association ends up accelerating the destruction of the forest, as shown in a recent report by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC).

“One of the trends we are seeing is an increase not only in crimes affecting the environment, but also in the convergence of various criminal activities,” says Hanny Cueva Beteta, head of UNODC’s global program on crimes affecting the environment.

In the opinion of Melina Risso, research director at the Igarapé Institute, there is an aggravating factor: The state agencies that fight money laundering still don’t focus on environmental crimes. “And this is reflected in the [devastation of] the Amazon,” she adds.

Between 2018 and 2022, deforestation grew by 53% in the Amazon, according to the Prodes system of the National Institute for Space Research (INPE). The most critical period was between August 2020 and July 2021, when the biome lost more than 13,000 square kilometers of native forest, almost nine times the area of the city of São Paulo.

The populations of the region are also suffering, as the vast network of crimes strengthens criminal factions and increases the rates of violence, according to UNODC. The organization’s report cites that the municipalities of the Legal Amazon registered 29.6 homicides per 100,000 inhabitants in 2021, a figure higher than the country’s average: 23.9 homicides.

Gold and money laundering

Gold fits into this network of illegal activities because it is difficult to trace its origin, says Hanny Beteta. It is common for illegally mined ore to be mixed with legal gold in refineries. As a result, it enters the international market and can be purchased by major brands such as Google, Microsoft, Apple and Amazon, as Repórter Brasil revealed in July 2022.

“Control over wood and meat is much greater today than over gold,” says Marivaldo Pereira, secretary for Access to Justice at the Ministry of Justice.

The ease with which criminals use gold as a “medium of exchange” was addressed in a recent study by the Igarapé Institute on money laundering in the Amazon. “It’s enough to report a different degree of purity in the ore and it’s already possible to hide [launder] resources with gold,” explains Melina Risso.

This is because, after extracting the ore from the ground, the prospector must register the production with the National Mining Agency, pay the tax due and report the gold content of the sample. Because it is common for other substances to be present along with the gold, the real value of a nugget varies – which opens up loopholes for money laundering.

In an export operation, for example, if the owner of a 1 kilo bar of gold tells customs that it is 99.9% pure, the product could be sold for around R$300,000. But if the content is in fact 66%, its real value is no more than R$200,000.

In order to trace the origin of gold in Brazil, the Federal Police have been running a program for four years to collect samples from various mines across the country. The aim is to compare the physical and chemical characteristics of seized cargo with the database and thus identify the origin of the ore. The police’s Ouroteca—the name of the database—already has more than 400 samples from exploration sites, whether industrial or illegal miners.

This technique is used by the police in investigations into the illegal gold trade, such as the 35 kg cargo of Amazonian gold prevented from leaving Brazil for the United States in 2020, which is still the subject of a legal dispute between the Federal Government and a New York company, as Repórter Brasil revealed.

Even with these advances, there are still bottlenecks in identifying the origin of gold, especially if the material has already gone through the refining phase, when a bar reaches 99.9% purity.

Experts explain that this makes it difficult to analyze substances added to the main ore – it is precisely these substances that help experts identify where the gold was extracted.

From dismantlement to control

The strengthening of organized crime in the Amazon is seen as a legacy of the Bolsonaro administration, which would have left the “door open” for these groups to operate, says Marivaldo Pereira, from the Ministry of Justice.

“There was a dismantling of the inspection bodies throughout the state structure,” says Pereira, referring to the cut in funds for operations by the Federal Police (PF), Ibama (Brazilian Environment Institute) and Funai (National Foundation for Indigenous Peoples), during the administration of the former president.

Since 2014, the Ministry of the Environment and its affiliated entities have been facing constant budget cuts, and under the Bolsonaro government, this situation has worsened, according to a study by Observatório do Clima. In 2021, the government allocated R$ 127 million for environmental enforcement and firefighting, a 35% reduction compared to the authorized expenditure for this purpose in 2019.

Another mistake would have been Bolsonaro’s bet on the Armed Forces to control the devastation of the Amazon. With operations Verde Brasil I and II, under the command of then vice-president Hamilton Mourão, the government inflated spending on the military apparatus, although it reduced spending on environmental inspection. The result was a drop in environmental fines and record levels of deforestation and fires.

Mourão, who currently serves as a senator for the Republicanos party in Rio Grande do Sul, was contacted for a comment but did not provide a response.

In order to reverse the situation, in January the police created a division focused on environmental crimes, especially those occurring in the Amazon. Since then, operations have been carried out on Indigenous lands in three states in the region.

“The same logistics as for drug trafficking are used for gold, and the plane that carries the laundered money can also bring in weapons. All these crimes have an impact on the environment and also on Indigenous communities,” explains Humberto Freire, the delegate in charge of the new police department.

According to Freire, the police are working to set up a cooperation agreement with eight countries that are part of the international Amazon in 2023. The aim is to share information on environmental crimes, along the lines of what the police already do with other nations in relation to money laundering and international drug trafficking.

In Congress, a bill presented by the federal government aims to reduce the bottlenecks in mineral control in the country. The proposal foresees the creation of a Gold Transportation and Custody Guide, a document similar to the one that already exists to regulate the transportation of cattle.

The bill currently being considered in the House of Representatives also wants to put an end to the so-called “presumption of good faith”. In practice, if the law is passed, those who buy illegal gold will not be able to claim ignorance of the origin of the ore and will be held legally responsible. In April this year, the Federal Supreme Court (STF) had already suspended good faith in the purchase of gold.

One of the authors of the bill is Marivaldo Pereira. “There are a lot of people who make money because of the ease with which you can attribute a legal origin to gold that has been mined illegally. This is a central point of our work,” says the secretary.

*Translation: Fernanda Buffa