Miners in Ghana, fishers in Bangladesh and loggers in Brazil have two things in common: many are vulnerable workers often submitted to slave-like conditions while engaging in an activity destructive to forests, rivers and oceans. Another common element is that they often work extracting products destined for markets in Europe and the U.S.

“There’s always been a moral case to end slavery; now there is an environmental reason too,” says Kevin Bales in his latest book “Blood and Earth.” Co-founder of the advocacy group Free the Slaves and professor of Contemporary Slavery at the University of Nottingham (UK), Bales gathered seven years of research to unveil a cross-border and cross-industry connection between labor rights and nature protection.

“The key thing is how some groups are operating illegally. People are under violent control in forests that are supposed to be protected,” he said in an interview with Reporter Brasil, using cases of illegal logging in the Brazilian Amazon as examples of the same system he saw operating in Africa and Asia. Hiding out in illegality, small logging companies – which Bales refers to as slaveholders – are committing various crimes to extract resources at the lowest costs.

In this interview with Repórter Brasil, Bales discusses the fragile regulations that are failing to cut the flow of money between consumers and the networks facilitating human rights abuses and environmental destruction. And he tries to answer the toughest question: how to stop it.

Repórter Brasil — How are slavery and environmental destruction connected?

Kevin Bales — Environmental destruction creates enormous vulnerability, especially when we think about people who live in a greater harmony with the natural world. Those who work in agriculture, who live in cost lines, who are caught up in places where climate change and environmental destruction take the land out from under their feet. Either literally disappears under the sea level rise or through erosion, deforestation and sometimes, there will be a project where someone is building a dam and there are areas that are going to be flooded and the poor people who live there will be pushed away. That all just creates a lot of vulnerability. They are poor, roofless and maybe they are refugees. It creates [a] situation where people can be enslaved.

On the other side, people in slavery are being used, being forced to particularly cut down forests from protected forests all over the world. Slavery is the root of a significant part of environmental destruction, especially in terms of CO2 emissions. Based on the deforestation rates and doing it very conservatively, we determined that if slavery were a country, it would be the third largest emitter of CO2 after China and the United States.

Repórter Brasil — What connects slavery in the logging sector in Brazil with realities such as Congo’s coltan mining or India´s shrimp farms?

Kevin Bales: One of the things that has happened in all these places is that environmental protections brought in laws and treaties…except virtually none of them actually have any sort of muscle in their protection. They state: “This is a protected forest,” but no one is hired to protect it. When they do hire, you have cases like in Africa, where two men [on] one bicycle have to cover hundreds of thousands of kilometers of forest, while the criminals have helicopters, trucks, airplanes and whatever they need.

When you look in illegal logging in Brazil, it is happening in places where the forest is supposed to be protected. I appreciate that, at local level, that is an issue often controversial. Because some will claim: “we need to open these places up to development.” But the key thing is that people are working under violent control in forests that are supposed to be protected.

Read the other reports:

Suppliers of Lowe’s in the US and Walmart in Brazil linked to slave labor in the Amazon

Investigation reveals slave labor conditions in Brazil’s timber industry

Slave labor in the Amazon: risking lives to cut down the rainforest

Repórter Brasil — You say that we can change this system by adopting small inconveniences, like paying attention to what we buy. But do we have enough information to make this choice?

Kevin Bales — In many cases no. Every day someone asks me: “How do I find out? Where is the list?” There are some lists available, and there is some research going on. But not as much as you need to be able to make these choices.

But we are getting there slowly; it’s a very difficult area to police and to research. Often the criminals are hiding behind “front” people. Even the people who are inspecting supply chains will find it difficult to penetrate down to the bottom level. And once criminals are exposed, they will move to a different supply chain. So it’s about constant vigilance.

But I do feel optimistic in that so many people are saying: “I want to know more, I want to find out,” and more and more organizations are working to make it possible.

Repórter Brasil — This interview is being published as part of a wider investigation, in which we discovered that sawmills held responsible for slavery in Brazil were connected to the supply chains of big brands in the U.S. The companies allege that the specific product is not the same as the one extracted by slave labor, but they do not open the tracking information. Shouldn’t this information be public?

Kevin Bales — Of course this should be public information. There is no way around that. If they are claiming that to be the case, they should be able to demonstrate it. Are you just supposed to take their word for it?

Repórter Brasil — There are also the certification groups that monitor the supply chain. But, in these cases, they failed. Who audits the audit companies?

Kevin Bales — There is not much auditing of auditing. There are few groups that are trying to promote ethical investments that will dig into this. We are in the beginnings of a period of time that can take 20 to 30 years as we work out precisely how to keep these things transparent and under control.

Repórter Brasil — What is the most effective regulation to ban products linked to slave labor?

Kevin Bales — The “Dirty List of Slave Labor” in Brazil, if it was done correctly [The “Dirty List” is a list of companies held responsible for slave labor, the publication of which is currently suspended by the Brazilian government]. I would like to see more countries using this system; it is very powerful.

Also, the system that was [introduced] in the state of California and now in the United Kingdom, where you require a certain transparency from very large companies. The law applies to companies that are above a certain size. These companies have to report, every year, what they are doing to both investigate and to remove slavery and trafficking from their supply chains.

It is a good place to start, but not a good place to finish, because that’s all they have to do: report. If they find slavery in their supply chain, they are not punished. That sounds maybe weak, but the reason we were able to pass that law in California is because business groups were willing to support a law that did not have penalties.

If they were able to talk freely about their problems instead of keeping them a secret, then they had an opportunity to come clean, everybody playing on a level field. That created a context where you could begin to open the whole thing for discussion and get people to start doing what needs to be done without feeling threatened.

The idea was to create a situation where they wouldn’t feel like they are just putting a gun to their heads. They were, in fact, having an opportunity to become visible, and begin to move in the direction of the next step.

Repórter Brasil — Do you see any real perspective of when this next step is?

Kevin Bales — Not exactly. Except that in a lot of countries people are debating slavery in supply chains. Some country is going to say: “reporting is not good enough, we are going to put a little bit more teeth into the law.” I think that these laws will simply continue to grow teeth overtime. But I would like it to be faster.

I have been following a bill that is aiming to put $250 million into anti-slavery work: the Corker bill [End Modern Slavery Initiative Act, introduced by U.S. Senator Bob Corker, Tennessee]. [It is a] recent bill in the U.S. congress that is said to do that kind of remarkable investment in anti-slavery. They [U.S. government] are going to allocate $250 million over time, and expect other organizations and countries also to kick in. I know they have talked to the government of the UK, for example.

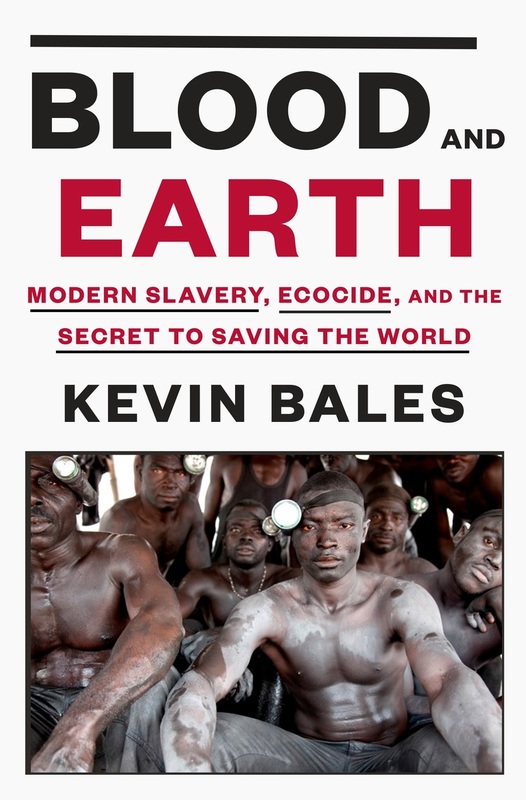

Shrimp farm workers in Bangladesh. Image courtesy of Kevin Bales

Repórter Brasil — Are there other international regulations that are already more effective in banning products connected to slavery?

Kevin Bales — I don’t know if I can point to someplace that is doing a great job. It’s interesting that in the United States they have a number of laws on the book and some of then go back to the 1930s that are very strong, but not necessarily understood to be enforced. In most countries there are equations about jurisdiction, so they say: “we don’t want anything to be imported that has slavery,” but their jurisdiction does not reach to other countries – in the sense that they can’t go to other countries to inspect. So they have to rely on businesses paying auditors. I am sorry to say it, but I feel like we are still in the early days here.

Repórter Brasil — Are the labor and the environmental policy-makers joining efforts?

Kevin Bales — They are beginning to join together. Some very senior people in the environmental world have said that, in the moment, the environmental movement can’t seem to move forward. A lot of countries are beginning to turn against environmental protection, like the United States. We know that everyone is against slavery. Since slavery is being used to hurt the environment, then let’s focus on slavery and have a win-win protecting it from both directions.

The big thing that is missing in the entire solution is the role and resources of governments. It is a huge problem, but most governments devote virtually no resources to solving this. It is as big as murder in many countries, where there are more people in slavery than are people getting murdered. But, for every 100 dollars spent to fight murder, they will spend 1 penny on slavery – or less.

Interview part of a special feature: Wood and Slavery (English version of the special “Profissão Madeireiro”)