[et_pb_section fb_built=”1″ _builder_version=”3.22.3″][et_pb_row custom_padding=”||0px|||” custom_margin=”|auto|-56px|auto||” _builder_version=”3.22.3″ background_size=”initial” background_position=”top_left” background_repeat=”repeat”][et_pb_column type=”4_4″ _builder_version=”3.0.47″][et_pb_text _builder_version=”3.22.4″ background_size=”initial” background_position=”top_left” background_repeat=”repeat” custom_padding=”||12px|||”]

While health agent Quitéria Ferreira dos Santos checks the size of freshly caught traíras (tiger fish), she explains how life works in the outskirts of Presidente Kennedy, a town in the south of Espírito Santo where this state border with Rio de Janeiro. “Everything is connected here. Riverine people fish in the river and the lagoon while the quilombola [slave-descendant communities] work the fields with their plantations. And beach communities make their living out of the sea.” Everyone agrees that both the beach and this harmonious way of life have their days numbered: construction of Porto Central is underway. On its own website, the development funded by Brazilian and foreign capital is called a huge “industrial port complex,” which will be built less than 40 kilometres from Marataízes, a well-known tourist destination on the southern coast of Espírito Santo.

In order to understand the project’s magnitude, one has to think that the port will be able to receive oil ships of almost 1 kilometre in length – the equivalent of ten football fields lined up. In total, it will occupy a 2,000-plus-hectare area now enclosed by barbed wire. The complex will also have a canal for ‘parking’ ships, containers, and cranes, penetrating about three kilometres into a strip of land now covered by undergrowth and Atlantic Forest. Until 2006, small farmers lived in the area, but they ended up selling their land to the enterprise.

The project’s environmental liabilities are shocking even a for biologist who preferred not to have his name disclosed. He works for environmental analysis company Econservation, hired by Porto Central to carry out studies at the mouth of the Itabapoana River, in the neighbouring town of São João da Barra. “Thermoelectric power plants will be built along the river to take advantage of the port’s infrastructure. The impact on the local ecosystem will be huge,” he told Repórter Brasil.

According to the project’s CEO José Maria Vieira de Novaes, Porto Central has an initial investment of BRL 4 billion – and its main shareholder is Brazilian concrete company Polimix, which controls the holding company TPK Logística. Another partner was the Port of Rotterdam (The Netherlands), Europe’s largest, which ended up leaving the project after seeing no viability in the business. Dutch construction company Van Oord is also involved. It participated in the construction of Suape, in Pernambuco, a massive port denounced at the UN in 2017 for causing socio-environmental damages to local communities. These violations were described by Repórter Brasil.

According to its CEO, the operation will start gradually. In the first stage, “it will be used to ship out the most urgent cargo: oil extracted from places like the Campos Basin.” In the following stages, it should receive oil and gas refineries and shipyards for vessels transporting the output from the pre-salt oil area already auctioned but not yet explored in the region. “The task now is to sign contracts with the foreign companies that bought these oil wells at pre-salt auctions,” explains the CEO, who declined to reveal their names. He said that the project includes construction of several factories and facilities for other companies – “in its large industrial park”, including thermoelectric plants.

“Thinking of factory chimneys giving off smoke is terrifying. And, at sea, a line of oil tankers entering this canal that will tear the land up to the highway,” complains artisan Rosângela Maria da Rocha.

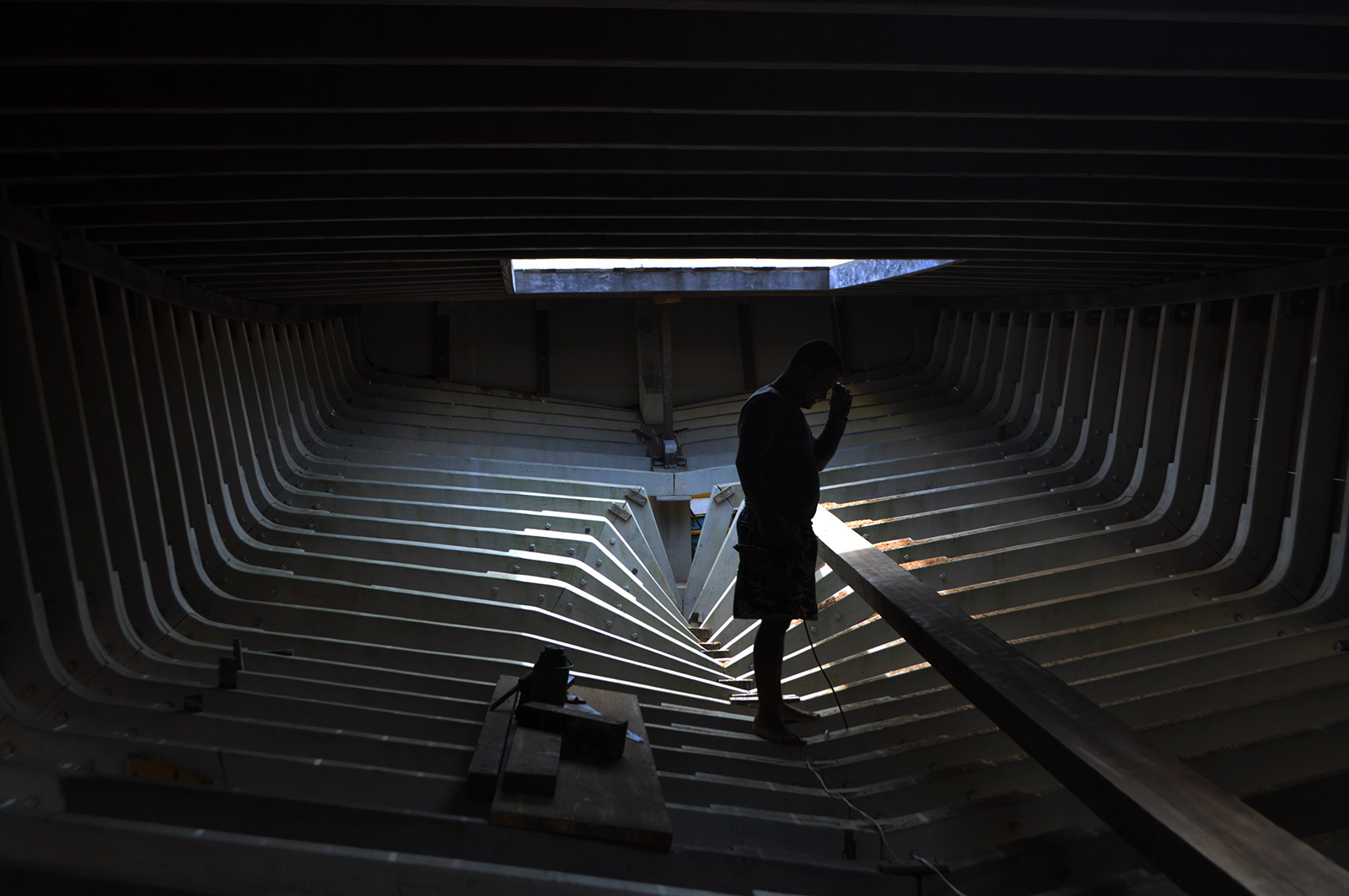

Always accompanied by music from his radio, Alfelino works with sandpaper to level a beam crossing the hull of the boat he is building on the banks of the Itabapoana River (Photo by João Cesar Diaz/Repórter Brasil)

Always accompanied by music from his radio, Alfelino works with sandpaper to level a beam crossing the hull of the boat he is building on the banks of the Itabapoana River (Photo by João Cesar Diaz/Repórter Brasil)“I was born and raised in this mangrove. I’d be lying if I said otherwise,” says 29-year-old Heloísa dos Santos Silva. Lit by a single bulb in a modest fishmonger’s store by the riverbank, she cleans peroás (Balistes capriscus), the local typical fish, at the speed of someone who has done it for over 15 years. “The entire community of the mouth of the Itabapoana River lives on this river and on this mangrove.”

The port claims to have the required environmental licenses, but Ibama says that no permission has been issued for so-called vegetation suppression (deforestation). An executive order issued by then President Michel Temer expedited the permission for vegetation suppression in the area, calling the port ‘infrastructure of national interest.’

As for social impact, Porto Central recognized that the work will harm the fishing activity. In a pamphlet distributed at the beginning of the project, the company states that it will directly affect the work of fishermen from Presidente Kennedy and neighbouring Marataízes and São Francisco do Itabapoana. To compensate for it, they promise to hold workshops to train those people so they can work in the construction.

Progress for whom?

However, for Presidente Kennedy’s mayor Dorlei Fontão (PSD), there is no need to worry about the impacts on the waters and the populations that depend on them, since there are no fishermen in town. “What you’ll find on the beach are some crooks who can’t even tie a line to a hook,” he says. “There is only the building of the fishing association here. If you look, you won’t find one fisherman.”

“If it were up to me, I’d put that port up there tomorrow,” he said in an interview with Repórter Brasil, adding that “the tractors will go over the entire area” in late August to start digging the canal. With his elbows over the table in his office, Fontão puts his palms together like someone who is tired of saying the same thing and repeats that fishing makes no contribution to the town’s tax revenues, while Porto Central will be beneficial to the population. “It will bring income, companies, all of that,” he adds, without giving details.

“Politicians and the port people say that this is progress coming. But what they are going to do here is to take the sea from the fisherfolk, the river from the riverine communities, the beach and nature from us,” says Mrs. Dora, as 65-year-old Maria Auxiliadora Araújo is known, while she sits in her room’s rocking chair, framed with flowers handmade out of local fish scales, branches and shells. “We don’t live on progress here but rather on what the sea and the land give us.”

CEO Novaes says that the progress to be brought by Porto Central will also come in the form of employment. He guarantees that there will be 4,000 jobs – 70% of which will be for local labour. But residents do not seem so confident. “Will there be work? Yes, but not for most of us,” objects Rosângela Maria da Rocha, secretary of the Association of Sea Artisans.

Fisherfolk are sure that their livelihoods have their days numbered. “I’ve been fishing since my teeth came out. That much-promised port will be the end of fish. The end of fishing. How are we going to work with all those tugs, oil tankers, and cargo ships around?,” says 66-year-old Valdecir, who lives by the river. Fisherman Haroldo dos Santos agrees: “With the port, the first thing they are going to do is to ban our little boats.” Alfelino Batista, a boat maker who learned the trade “from [his] father, who learned from [his] grandfather and there goes a lot of history,” says he is sure that his work will end as soon as Porto Central is ready.

‘Those royalties don’t belong to us’

When residents speak, they always sound like someone who seems tired of promises of improvement in their lives. It happened back in 1999, when the town began to receive royalties from oil and gas. Presidente Kennedy has the fourth highest GDP per capita and receives the highest oil and gas royalties among Brazilian municipalities – over BRL 160 million per year, according to the National Petroleum Agency. That is quite a lot for a population of 10,000.

But as it seems, the oil money has never reached the town’s dirt streets or the flooded roads around it. It has not reached the people either. “These royalties don’t belong to us; that’s our feeling,” says Efigênia Alves Peris, president of the Cacimbinha and Boa Esperança Quilombo Residents’ Association.

Riverine and quilombola communities are also wary because of the Port of Açu, built in 2013 in São João da Barra, 70 kilometres from Presidente Kennedy. “What they are saying about Porto Central is something we’ve heard before, but then nothing was delivered,” says Batista the boat maker, referring to the Port of Açu. “They promised employment, they promised courses, but after the construction finished, they only hired outsiders.” He worked at the port during construction and dredging: “It was a terrible job, pay was low and often late… We didn’t even know what we were building. For me it was like slave work, but we needed the money.”

Questioned by Repórter Brasil, Porto do Açu states that it “strictly complies with labour legislation” and its policy is to hire local labour “from São João da Barra and Campos dos Goytacazes.” Residents interviewed, however, say that most of the “good jobs” are for people brought from other places and who now live in the city of Campos.

Initially conceived by Brazilian businessman Eike Batista, Porto do Açu was one of the central pieces in the plea agreement signed by former Rio de Janeiro governor Sérgio Cabral (PMDB) in which he was to point to other people involved in corruption. Investigations under the so-called Car Wash (Lava Jato) Operation point to a connection between bribes paid by Batista and executive orders facilitating land expropriation for the development in São João da Barra. Control of Açu is now – as in the case of Porto Central – divided between a Brazilian logistics company (Prumo Logística) and a European port (Port of Antwerp).

According to fishermen from Presidente Kennedy, the Port of Açu is already disturbing their lives, since cargo ships coming from there scare part of the fish away, making it increasingly difficult to live on fishing. “I don’t want my son to be a fisherman, it’s not possible anymore” – said several fishermen.

Ana Maria Almeida da Costa, a professor at the Department of Social Services of Fluminense Federal University (UFF) who studies the socioenvironmental impacts of Porto do Açu, points out its poor and degrading working conditions: “There are several reports of labour law violations and episodes that could be considered slave labour,” she says, emphasizing that labour inspectors have not yet looked into those cases. “The port was imposed overnight, expropriating the lands of about 1,500 families of small farmers and fisherfolk in a brutal and violent way.”

The professor says that Porto Central seems to repeat Açu. “Due to lack of transparency on the part of the port, residents will only be aware of the size of the ‘monster’ when it appears,” she says.

From the Sea to the Parish

The future central area of the port is located about four kilometres from the beach in Presidente Kennedy. There, disguised within the landscape of royal poinciana trees, cacti and shrubs, a dirt road leads to the Sanctuary of Our Lady of the Snows, built at the request of the Jesuits in the early 17th century. That is where 58-year-old Jovelina Alves Peris lives. She has looked after the sanctuary for 18 years and points to the place of the first house where the prayer group used to start – today in ruins taken by barbed wire and Porto Central signs.

The purchase of the area began in 2008, when the company Ferrous Resources do Brasil, which owns iron ore mines in Brumadinho, Minas Gerais, gradually purchased every lot and then sold them to Porto Central. “As soon as they bought it, they’d already pass the tractor over it to bring down the houses.” At the time, the mining company planned to build its own port and slurry pipeline to transport its product from Minas Gerais.

The model of Porto Central includes space for the Sanctuary among the industrial buildings. But even so, Peris fears that the church will be swallowed up by the sea. “They are going to cut the land to our gate.”

[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row][/et_pb_section][et_pb_section fb_built=”1″ _builder_version=”3.22.4″ custom_padding=”0px|||||”][et_pb_row _builder_version=”3.22.4″][et_pb_column type=”4_4″ _builder_version=”3.22.4″][et_pb_gallery gallery_ids=”46052,46065,46062,46057,46056,46053,46054,46059,46066,46063,46064,46060,46055″ fullwidth=”on” _builder_version=”3.22.4″][/et_pb_gallery][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row][/et_pb_section][et_pb_section fb_built=”1″ _builder_version=”3.22.4″ custom_padding=”6px||0px|||”][et_pb_row _builder_version=”3.22.4″][et_pb_column type=”4_4″ _builder_version=”3.22.4″][et_pb_text _builder_version=”3.22.4″]

This report was made with support from DGB Bildungswerk and Fonds Pascal Decroos

[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row][et_pb_row _builder_version=”3.22.4″][et_pb_column type=”1_2″ _builder_version=”3.22.4″][et_pb_image src=”https://reporterbrasil.org.br/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/FondsPascalDecroos_logo.jpg” _builder_version=”3.22.4″][/et_pb_image][/et_pb_column][et_pb_column type=”1_2″ _builder_version=”3.22.4″][et_pb_image src=”https://reporterbrasil.org.br/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/dgblogo.jpg” _builder_version=”3.22.4″][/et_pb_image][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row][/et_pb_section]