No one walks alone anymore, drives on the roads at night or paints themselves with genipap to go to the cities. In the municipalities of Acará and Tomé Açu, in northeast Pará, indigenous and quilombola communities take turns keeping vigil at the entrance to their territories.

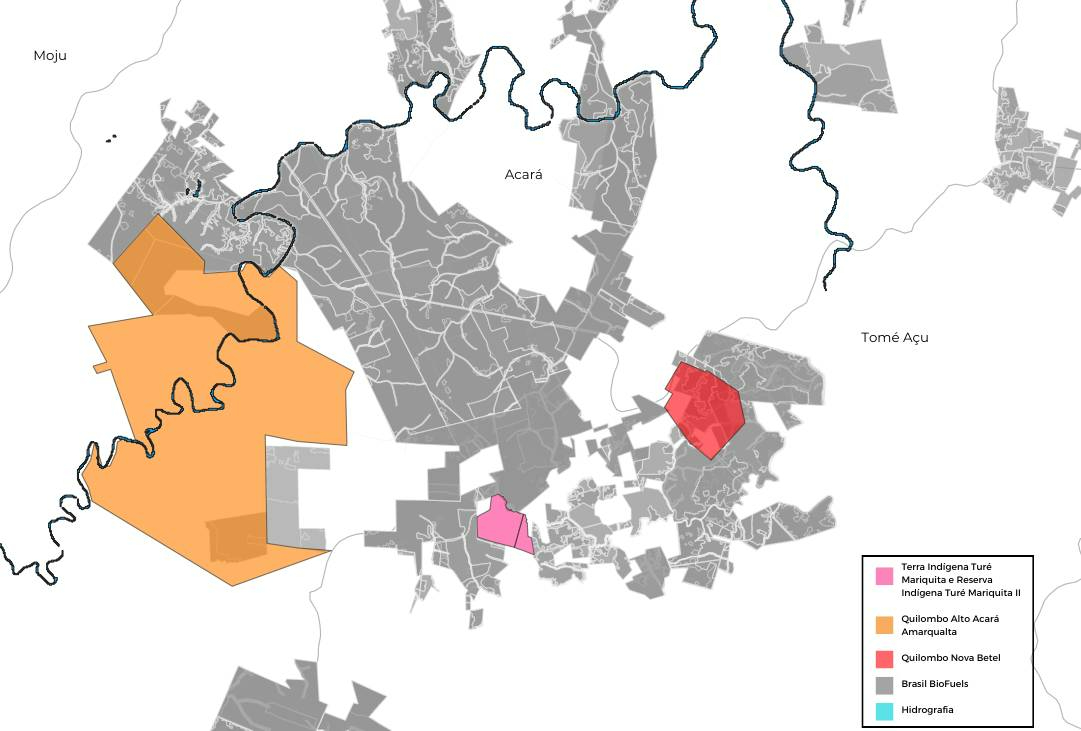

Surrounded by oil palm plantations, residents of the quilombos Nova Betel, Alto Acará Amarqualta and the indigenous land Turé Mariquita live a scenario of terror since the palm oil producer Brasil BioFuels (BBF), which claims to be the largest in Latin America, settled in the region, 200 km from Belém.

The oil palm groves, bought by BBF in 2020, cover both sides of the dirt road that leads to the traditional communities. The delimitations of the three territories are in dispute in the courts. The quilombola families have been waiting more than 10 years for the titling of the two areas. The Tembé people have been requesting, since 2016, the extension of their 147-hectare indigenous land demarcated 30 years ago.

While the communities struggle for the regularisation of their territories, BBF claims to own farms overlapping the claimed lands. Amid the land ownership chaos, a climate of threats and violence is intensifying in the region. “It is the oil palm war”, say the people.

Flying high

BBF entered the Pará market by acquiring Biopalma, then a subsidiary of mining company Vale, and now controls 56,000 hectares in the state. The company’s cultivation area, equivalent to 78,000 football fields, is located in the Acará Valley and Lower Tocantins regions, the largest palm oil producing region in Brazil.

The company is dreaming big: in April, it signed an exclusive commercialisation agreement with the country’s largest distributor of jet fuel, Vibra Energia, which serves 90 airports and accounts for 70% of the domestic market. The companies announced an investment of R$ 2 billion to produce biodiesel made from palm oil.

The commercial partnership takes place in a context of incentives to reduce carbon emissions in aviation, so Gol, Latam and Azul “have shown interest” in the fuel.

Away from the offices, the reality is different.

Indigenous and quilombola communities say that BBF unilaterally broke agreements signed with the traditional communities living around the oil palm plantations, which provided support for the small plantations and the construction of artesian wells. The shares were held by Biopalma, one of the first companies to set up in the region, in 2007. “They bought the farms ‘with closed gates’, with the cattle inside. But it wasn’t cattle, it was us”, says Emídio Tembé.

In November, tired of waiting for the agreements to be fulfilled, the indigenous people occupied areas of oil palm plantations in the parts of the territory they claim as an extension of the indigenous land Turé Mariquita, creating small camps. In January, it was the turn of the Nova Betel quilombolas to occupy palm areas and the following month, the Acará Alto Amarqualta quilombolas took over part of the plantation. In reaction to the occupations, an escalation of violence occurred in the region.

At the beginning of July, around midnight, a car drove into the camp known as Solimões, formed by Indians who call themselves Turiuara and located at the limit of the area claimed as an extension of the indigenous land Turé Mariquita. Shots were fired and a resident was hit in the chest but survived. Witnesses recognised the uniform of the shooters: they were from Stive Security and Surveillance, which provides services to BBF.

“Unfortunately, the bloodshed has already started”, comments a victim who prefers not to be identified.

This was not an isolated incident. In April, a quilombola was arrested after being assaulted by company security guards. On that occasion, a group of indigenous and quilombola people occupied the BBF headquarters in Acará in protest against environmental and human rights violations practised by the company. At the end of 2021, indigenous people reported that they were cursed at and beaten by employees linked to BBF. Quilombolas claim that five houses were burned down in their territories.

The actions are not restricted to physical aggression. Two large ditches were opened on the road that connects the indigenous land and the indigenous reserve Turé Mariquita II — an area of 587 hectares created in 1996 — to the quilombo Alto Acará Amarqualta, preventing the mobility of more than 700 families. The leaders believe that the company is behind the violence and denounce the use of militias. “It won’t take long to mourn the bodies of our relatives”, comments Adenísio Portilho, leader of the Turiuara. In response to Repórter Brasil, BBF said that “there is no overlapping of areas with the territories of traditional communities” and that “it exercises peaceful, fair and uninterrupted possession of its areas”.

The company denies any episodes of beatings, threats or burning of houses by security agents, and classified the attack on the Solimões camp as a “fanciful situation”. It also said that there is an “inversion of the narrative that seeks to transform the company into a great villain”.

BFF also says that indigenous people and quilombolas invaded the company’s land after the high price of palm oil to steal the fruit and sell it to competitors in the region (Read the company’s full answers here).

Mário Gonçalves Trindade, president of Amarqualta, an association that represents the quilombo of Alto Acará, reiterates that the occupation occurred because of the breach of agreements and says that he tried to dialogue with the company “as far as possible”.

By telephone, a Stive Security employee, who identified himself only as Andrade, said that company representatives received the questions sent by Repórter Brasil, but that they would only answer “if there are photos that prove that the company shot or assaulted”.

The encouragement of violence gains support from local politicians. “Where justice does not reach, gunpowder must reach”, said Deputy Delegado Caveira (PL) at a demonstration by BBF workers in Belém in April against the actions of indigenous people and quilombolas.

Two months later, it was the turn of senator and pre-candidate for governor of Pará, Zequinha Marinho (PL), to come out in defence of the company. In an audience in Tomé Açu, Marinho said he would go to the Ministry of Justice to ask for action against the theft of the fruit denounced by BBF.

Sought by the report, Zequinha Marinho’s press office said that the senator sought support from the Ministry of Justice “to put an end to social tensions arising from agrarian conflict”, but did not detail which were the steps taken with the federal agency. (Read full text)

Deputy Delegado Caveira did not comment.

Palm oil to fuel planes

Signatory to the Paris Agreement, Brazil is in a race to zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050 and contain global warming.

The aviation sector is responsible for 2% of global CO2 emissions in the atmosphere and is studying alternatives. One of the main measures is the replacement of diesel with sustainable aviation fuels (SAF). The April event celebrated the billionaire partnership of BBF for the exclusive marketing of SAFs, from 2025, with Vibra Energia.

“It is not possible to consider this product sustainable while traditional populations are claiming their territories and being affected with poison”, says Rômulo Batista, from Greenpeace’s Amazon campaign.

“What palm oil companies are saying about sustainable clean energy is false. They are killing the environment, the traditional peoples and will end up with the planet”, warns Josias dos Santos, public relations coordinator of the Association of Residents and Remaining Quilombola Farmers of Alto Acará (Amarqualta).

In response to Repórter Brasil, Vibra Energia said that the contract with BBF is restricted to the acquisition of palm planted in the state of Roraima and that it initiated an internal due diligence to assess the agrarian conflicts, “which was fully met”. Vibra said it will continue to monitor the case (Read the answers here).

In a statement, the airlines Gol, Latam and Azul said they had no commercial ties with BBF and that their visit to the event was only to learn about the project. The Ministry of Mines and Energy, which was also invited to the meeting, responded that the visit “was eminently technical”. The BNDES (The National Bank for Economic and Social Development) said it participated “in order to verify the possibility of financing investments in the production of renewable energy” and that, after becoming aware of the conflict, it asked the company for clarification. (Read the answers here).

650 police reports

In addition to physical violence, BBF has relied on another strategy: the registration of police reports against community members, with reports of theft of palm oil and aggression against company employees. More than 650 have already been registered. Repórter Brasil had access to a civil police report from January this year, which says that the company’s demand “has completely halted the work” of the corporation in Quatro Bocas and Tomé-Açu, leading the police station staff “to exhaustion”.

Despite the numerous records, according to the police, the company does not collaborate with the forwarding of processes, failing even to provide statements, besides registering false information.

In an attempt to take the focus off the land problems, BBF acts strategically to criminalise members of traditional communities and creates a climate of insecurity for families, assesses Andreia Barreto, from the Pará State Public Defender’s Office. “A company that acts in this way is comparable to gunmen”.

Land chaos spurs violence

Four members of quilombola communities have been murdered in the Alto Acará Amarqualta territory since the demand for recognition of the territory began, in 2010. “We lost people because we began to understand what it is to be quilombola, and we began to fight. I fear being next”, admits Josias dos Santos.

Repórter Brasil had access to a report from April this year from a commission that analyses issues related to land grabbing, linked to the Pará Court of Justice, which recognises the existence of “overlaps with federal and state lands, currently occupied by the company and by the communities”, but which could not “give better effectiveness to the conflict” as neither BBF nor the land title bodies responsible for regularising quilombola territories presented the documentation.

Jorde Tembé, the lawyer representing the indigenous people, also pointed out the absence of environmental licensing and the lack of consultation with the indigenous people when the companies were setting up in the region — at the time, palm planting was considered to have a low impact and was exempt from special authorisations. In June, during discussions to expand the indigenous land Turé Mariquita, the Federal Prosecution Service requested an anthropological analysis of the indigenous occupations in the region. A month later, BBF committed with the Pará justice to finance studies of the indigenous component of the territory claimed by the Tembé.

“We are the first inhabitants here and we were robbed by farmers, then by Biopalma [the former oil palm company in the region] and now by BBF”, emphasises Emídio Tembé, chief of the Tekna’i village. “That is why we are fighting for the expansion, because it is necessary to recognise our traditional territory”.

When asked by Repórter Brasil to clarify the lack of environmental studies on the occasion of Biopalma’s installation, the State Secretariat for Environment and Sustainability of Pará (Semas-PA) merely replied that the enterprise has an operating permit in force (read the full text here).

When questioned about the process of land regularisation of quilombola territories, INCRA (National Institute for Colonisation and Agrarian Reform) said that it will send a group to begin identifying and delimiting the areas in August, but that there is no deadline for completing the work. The agency states that only after a complete land survey will it be able to affirm if there is overlapping with the BBF farms. Iterpa (Land Institute of Pará) informed that the work is “under analysis by the competent bodies”. (Read the full responses here).

The National Indian Foundation (Funai) did not comment.

‘A territory where death is lurking’

Without an area dividing the crops and the traditional territories, the communities live with the impacts of oil palm monoculture, such as the use of pesticides, the disappearance of game and the increase in insects that destroy the crops.

Emídio Tembé no longer drinks xibé — a mixture of water and flour — on the banks of the stream. Since the plantations were installed in the area around the indigenous land, the old man cannot drink the river water without getting diarrhoea and stomach ache. His wife Elisa has stopped bathing in the river because of itching and allergies.

Adelina de Souza, Mrs. Dadá, says she was born “at the mouth” of the Karuara stream, in the Alto Acará Amarqualta quilombo. “I raised my children on this land. We are here long before the company arrived”. Without other supply alternatives, she and the other residents still use the water from the stream, which they fear is contaminated.

Besides the contamination of the waters, the quilombolas reported a decrease in fish and game. Tapir, peccary and venison meat, which used to be part of the communities’ diet, is becoming increasingly difficult to find. “Now it’s chicken, bologna. Before it was difficult for my grandparents to get sick. This has changed”, says Xandir Tembé, a nursing technician and granddaughter of Emídio and Elisa.

Reports of headaches, itching and difficulty breathing are common among the populations living in the palm groves, but cases are hardly reported due to the lack of preparation of local medical teams to classify them as intoxication.

“The greatest exposure to pesticides of the populations related to oil palm is environmental, that is, people used to live in that territory and oil palm reached them”, says Antonio Mota, from the Evandro Evandro Chagas Institute (IEC), linked to the Ministry of Health. According to the researcher, there is a significant increase in people living surrounded by oil palm plantations who present dermatological and respiratory problems due to exposure to pesticides.

A study published in 2017 identified residues of endosulfan — banned since 2010 — and glyphosate in the waterways that cut through Tembé lands in Tomé Açu. Widely used in Brazilian agriculture, glyphosate is classified as probably carcinogenic to humans by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), a body of the World Health Organization.

“This is an extraction model that has to do with the deprivation of basic rights. It’s a territory where death is lurking: you can’t bathe in the river, you can’t drink the water, you can no longer eat fish”, says Elielson Pereira, a researcher from the Federal University of Pará.

In a statement, BBF said it “follows the best international practices for the sustainable management of palm” and denied using pesticides in regions close to indigenous and quilombola lands. (Read the full text).